Fighting Human Slavery: Why the Private Sector Should Care

Human trafficking, which represents the recruitment, transport, receipt and harboring of people for the purpose of exploiting their labor, affects almost all parts of the world. Globally, it is estimated that there are over 50 million men, women and children in situations in modern day slavery today, with about half in Asia alone. These victims, who can be found in factories, construction sites, within fisheries and sex venues, are forced to work for little or no pay, deprived of their freedom, and often subjected to unimaginable suffering.

While most people think that human trafficking focuses primarily on women and girls being forced into the sex industry, this represents only about 25 percent of the total cases. The remaining 75 percent fall under the heading “forced labor.” Out of this figure, about 60 percent of the victims are associated with manufacturing supply chains, which begin with a grower or producer and end as a finished product purchased by consumers in the retail market.

Over more than a decade, the international human trafficking community has not come close to meeting its full potential. While individual, small-scale success stories can be found, many victims are never identified. For example, the 2022 Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP Report) was only able to account for 90,000 victims receiving assistance globally. During the same time period, there were less than 6,000 convictions. This means that less than one percent of the victims are being identified and assisted each year. This number has remained unchanged for several years.

Why are these numbers so low? According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), the profits generated from this illicit trade are estimated to exceed US$150 billion annually. But despite the size of the problem, annual global donor contributions add up to only around US$350 million, which represents approximately one percent of total profits generated by the criminals. With this in mind, it is not surprising that the number of trafficked persons continues to increase. In fact, the UN has indicated that there are more modern slaves in the world today than at any other time in history. For the world to really make a difference in addressing this problem, the private sector must become a player in this fight.

Why should the business world care about this? First, most forced labor cases have some direct or indirect link with the private sector. Unlike the United Nations and other civil society organizations, the private sector knows how to root out bad businesses and already has the necessary skills and capabilities to tackle the problem, e.g. legal, compliance, accounting, communications, and financial expertise. Second, labor trafficking often under-cuts the price of legitimate businesses, offering an unfair advantage to those involved. Third, when human trafficking conditions are found in a given business sector, it can result in an entire industry receiving a “bad name.” This trend is emerging in the electronics, garment, chocolate and seafood sectors. Fourth, this topic is becoming a growing public concern (similar to environmental issues), with more and more consumers asking questions about whether the products they buy are “slave free.” Fifth, with new legislation out of North America and Europe, it will be expected that most CSR/ESG declarations address this topic. Finally, and most importantly, slave-like conditions have been and will always be incompatible with good business.

What can retail and manufacturing companies do to play a role in addressing the problem? First they can look at their business to determine if there are any risk factors. Based on this risk, companies can take specific measures to maintain a slave-free supply chain, including:

- Conducting investigative audits that illuminate the real conditions faced by workers throughout the continuum of the supply chain and describe them in qualitative and quantitative degrees to top-level corporate decision-makers;

- Conducting action-oriented training for staff in global corporations and their suppliers with the goal of expanding awareness and helping reduce the negative impacts of global sourcing;

- Consulting at the points of maximum leverage on how to implement effective human rights protections within global businesses; and

- Facilitating multi-stakeholder initiatives that join private sector business, workers, labor, civil society and governments to focus on both strategic and practical levels with the goal of achieving positive social change.

Within the finance/banking world, the role that can be played is different. For example, the action of placing money, which is the proceeds from a prior criminal activity such as those comprising trafficking and forced labor, is money laundering. Current law and regulation places heavy requirements on the global banking system to ensure that money launderers are identified and reported and laundering stopped. An opportunity therefore exists to fight slavery and trafficking by identifying bank channels and utilizing the requirement placed on them to prevent money laundering if such activity is potentially occurring, actually suspected or identified.

In addition to these internal actions, companies can also ask themselves the basic question – “What if this was our problem — how would we go about addressing it?” Every corporation is encouraged to explore ways of using their skills, expertise and comparative advantage to be part of the solution. For example, a law firm could come up with legal remedies. A communications corporation could come up with technology and IT solutions. Having these contributions would help to come up with new, innovative approaches.

The time for these kinds of interventions is now. Companies all over the world can set their own agendas to take a leading role in addressing this issue. The necessary skills and capabilities to tackle the problem, whether it be legal, compliance, accounting, communications, or financial expertise, exist within the sector. With more emphasis on ESG and “business with purpose,” these efforts will demonstrate that the private sector is part of the solution, not the problem. Doing this could also significantly help reduce the number of human trafficking victims.

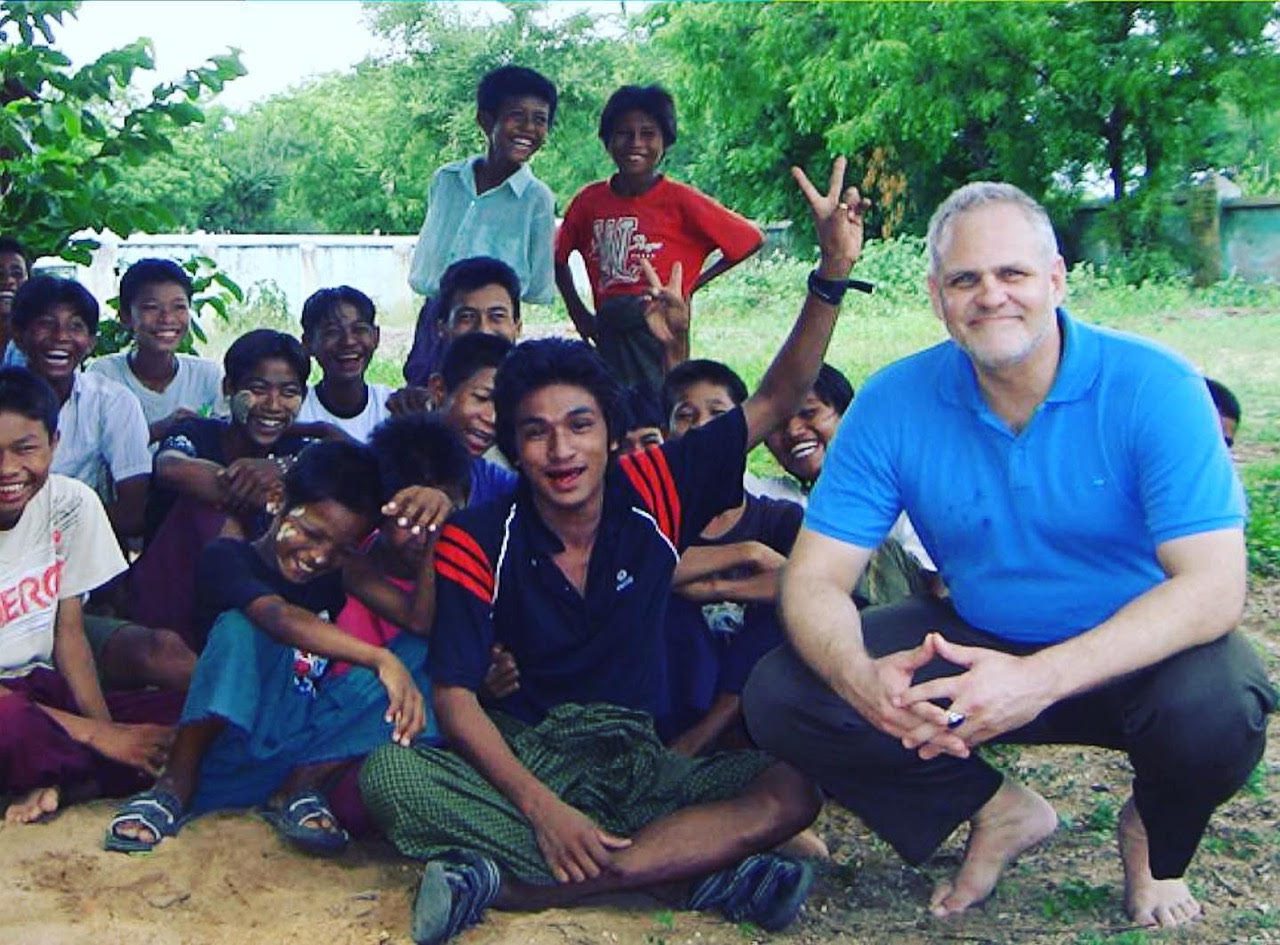

Matt Friedman, CEO, The Mekong Club- As the founder and CEO of The Mekong Club, Matthew Friedman is a global expert on modern slavery and human trafficking. An award-winning filmmaker, author and philanthropist, Matthew regularly advises heads of governments and intelligence agencies. Matthew is considered the leading catalyst of the anti-slavery movement in Asia’s business sector by captains of industry. Matt’s recent publications include Where were you?: A Profile of Modern Slavery and Be the Hero: Be the Change.

The Mekong Club– The Mekong Club works with the private sector to bring about sustainable practices against modern slavery across the globe. Companies can join the Mekong Club as Members to enjoy a range of benefits, anti-slavery tools, resources, and consultations. We have created a community of like-minded peers across different industries, working together to address modern slavery. Through these efforts, The Mekong Club’s mission is to inspire and engage the private sector to work together towards creating a slave-free world.