There Could be Labor Exploitation in Your Coffee Cup: Here’s How It Got There

Around the world, approximately 26 million people work on coffee plantations every year. Men, women, and children labor in countries along the equator picking the beans that, through murky supply chains, eventually end up in your local grocery store or café. But inside the billions of cups of coffee consumed every day, the bitter taste of modern-day slavery goes largely unnoticed.

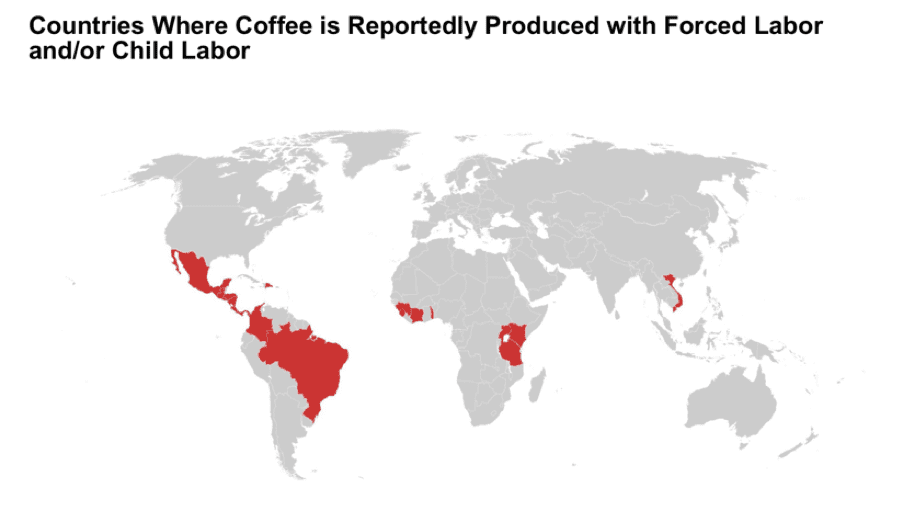

The number of people experiencing labor trafficking and exploitation in the coffee industry is unknown, as few large-scale studies on this problem have been conducted. What we do know, however, is that the problem is widespread and complex. In-depth reporting by Verité, Danwatch, The Weather Channel, and others provide crucial insight into working conditions on small farms and large plantations across the globe.

Brazil is the largest exporter of coffee in the world. In the state of Minas Gerais, a small number of labor inspectors race to rescue workers from slavery every harvesting season. Reuters reports that an estimated two-thirds of coffee farm laborers in Minas Gerais are informal workers, many of them seasonal migrants from neighboring towns and states. Without official work documentation, they are left with no legal claim to minimum wage, overtime pay, or labor rights protection as guaranteed by Brazilian law. Rescued workers report being denied access to sufficient food, clean water, basic safety equipment, and their wages. Some even end up in debt bondage when forced to work off the costs of their housing and food; without money to pay for the bus ride home, some families remain stranded on plantations. Similar stories play out in coffee-producing countries around the world.

Image: https://www.verite.org/project/coffee-3/

In addition to migrant workers, indigenous people, women, and children are highly vulnerable to labor exploitation in this industry. In Mexico, farmers rely on an annual parade of an estimated 30,000 destitute, informally recruited Guatemalan coffee pickers. Indigenous people who do not speak Spanish may be left without access to resources or information on labor rights. Women in particular tend to perform lower skilled tasks, work more hours overall, be paid less, and experience high rates of sexual assault. The data, however, are lacking. Much more research is needed to get a better statistical picture of the exploitation of female and indigenous workers.

Child labor is common on coffee farms, but the question of how to tackle it remains unanswered. In one leading industry insider’s words, “child labor is the norm these days in coffee,” due in large part to increasing production and declining coffee prices. Although large plantations receive the most attention during conversations about coffee pickers, family-run, smallholder coffee farms actually produce 60% of the world’s coffee; almost half of these families live in poverty. When coffee prices dip in this highly volatile market, families may be forced to put their children to work in order to avoid starvation. Similarly, migrant laborers often cannot afford to leave children back home or in school.

In March, the UK’s Channel 4 reporters filmed children under the age of 13 working backbreaking 40-hour weeks on Guatemalan coffee farms. Reuters found similar child-labor practices going on in Brazil where workers were paid $0.49 per hour. Farms in both places were reportedly supplying beans to Starbucks and Nestle, two companies that boast rigorous ethical standards for their beans.

Investigative reporting has revealed the many holes that perforate popular slave-free certification schemes. The problem is partially rooted in numbers. Programs like Fair Trade and the Rainforest Alliance follow what’s called the “square-root rule” to determine the number of properties to be inspected annually; as a consequence, just around 0.5% of farms are inspected every three years in large markets, and surprise audits are rare. And because coffee beans may change hands over 100 times along their supply chain, brands like Nespresso may end up stamping products as “ethically made” when they were in fact picked by modern-day slaves in Colombia, Vietnam, or Uganda. In short, Fairtrade programs alone simply aren’t equipped to identify, let alone systemically change, trafficking and labor exploitation in the billions of pounds of coffee harvest every year.

The current coronavirus pandemic is likely to make matters worse. Verité’s Cooperation On Fair, Free, Equitable Employment (COFFEE) Project is now examining the impacts of COVID-19 on coffee farmers and farmworkers. They report an increase in the risk of child and forced labor due to the designation of agricultural workers as “essential workers” as well as travel restrictions on migrant labor. The preexisting lack of PPE and proper sanitary measures on plantations and the halting of anti-slavery operations are other major concerns.

So, what can troubled coffee drinkers do? Specialty brands that source their beans directly from small farms may be one good option. You can find a list of more ethical coffee brands here. These individual programs, however, lack standardization or accountability. In the end, changes in individual consumption will not solve the problem of labor exploitation in the coffee industry. Instead, governments, businesses, and even Fairtrade certification schemes must turn their attention to addressing poverty and labor rights and standards that lie at the root of this systemic issue. Meanwhile, concerned citizens should watch for modern slavery and supply chain transparency bills in their states and lend their support to campaigns for such legislation. And over your next cup of coffee with a friend, try starting a conversation about what went into your brew.

Aubrey Calaway is a graduate of Brown University. She led unBUYnd, a grassroots campaign for supply chain transparency legislation in Rhode Island, for three years. She currently works as a research fellow at Human Trafficking Search.