THE COBALT PIPELINE Tracing the path from deadly hand-dug mines in Congo to consumers’ phones and laptops

Photos by Michael Robinson Chavez

The sun was rising over one of the richest mineral deposits on Earth, in one of the poorest countries, as Sidiki Mayamba got ready for work.

Mayamba is a cobalt miner. And the red-dirt savanna stretching outside his door contains such an astonishing wealth of cobalt and other minerals that a geologist once described it as a “scandale geologique.”

This remote landscape in southern Africa lies at the heart of the world’s mad scramble for cheap cobalt, a mineral essential to the rechargeable lithium-ion batteries that power smartphones, laptops and electric vehicles made by companies such as Apple, Samsung and major automakers.

But Mayamba, 35, knew nothing about his role in this sprawling global supply chain. He grabbed his metal shovel and broken-headed hammer from a corner of the room he shares with his wife and child. He pulled on a dust-stained jacket. A proud man, he likes to wear a button-down shirt even to mine. And he planned to mine by hand all day and through the night. He would nap in the underground tunnels. No industrial tools. Not even a hard hat. The risk of a cave-in is constant.

“Do you have enough money to buy flour today?” he asked his wife.

She did. But now a debt collector stood at the door. The family owed money for salt. Flour would have to wait.

Mayamba tried to reassure his wife. He said goodbye to his son. Then he slung his shovel over his shoulder. It was time.

The world’s soaring demand for cobalt is at times met by workers, including children, who labor in harsh and dangerous conditions. An estimated 100,000 cobalt miners in Congo use hand tools to dig hundreds of feet underground with little oversight and few safety measures, according to workers, government officials and evidence found by The Washington Post during visits to remote mines. Deaths and injuries are common. And the mining activity exposes local communities to levels of toxic metals that appear to be linked to ailments that include breathing problems and birth defects, health officials say.

A “creuseur,” or digger, climbs through a cobalt and copper mine in Kawama, Congo, in June.

The Post traced this cobalt pipeline and, for the first time, showed how cobalt mined in these harsh conditions ends up in popular consumer products. It moves from small-scale Congolese mines to a single Chinese company — Congo DongFang International Mining, part of one of the world’s biggest cobalt producers, Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt — that for years has supplied some of the world’s largest battery makers. They, in turn, have produced the batteries found inside products such as Apple’s iPhones — a finding that calls into question corporate assertions that they are capable of monitoring their supply chains for human rights abuses or child labor.

Apple, in response to questions from The Post, acknowledged that this cobalt has made its way into its batteries. The Cupertino, Calif.-based tech giant said that an estimated 20 percent of the cobalt it uses comes from Huayou Cobalt. Paula Pyers, a senior director at Apple in charge of supply-chain social responsibility, said the company plans to increase scrutiny of how all its cobalt is obtained. Pyers also said Apple is committed to working with Huayou Cobalt to clean up the supply chain and to addressing the underlying issues, such as extreme poverty, that result in harsh work conditions and child labor.

Another Huayou customer, LG Chem, one of the world’s leading battery makers, told The Post it stopped buying Congo-sourced minerals late last year. Samsung SDI, another large battery maker, said that it is conducting an internal investigation but that “to the best of our knowledge,” while the company does use cobalt mined in Congo, it does not come from Huayou.

Few companies regularly track where their cobalt comes from. Following the path from mine to finished product is difficult but possible, The Post discovered. Armed guards block access to many of Congo’s mines. The cobalt then passes through several companies and travels thousands of miles.

Yet 60 percent of the world’s cobalt originates in Congo — a chaotic country rife with corruption and a long history of foreign exploitation of its natural resources. A century ago, companies plundered Congo’s rubber sap and elephant tusks while the country was a Belgian colony. Today, more than five decades after Congo gained its independence, it is minerals that attract foreign companies.

Scrutiny is heightened for a few of these minerals. A 2010 U.S. law requires American companies to attempt to verify that any tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold they use is obtained from mines free of militia control in the Congo region. The result is a system widely seen as preventing human rights abuses. Some say cobalt should be added to the conflict-minerals list, even if cobalt mines are not thought to be funding war. Apple told The Post that it now supports including cobalt in the law.

Congo’s cobalt trade has been the target of criticism for nearly a decade, mostly from advocacy groups. Even U.S. trade groups have acknowledged the problem. The Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition — whose members include companies such as Apple — raised concerns in 2010 about the potential for human rights abuses in the mining of minerals, including cobalt, and the difficulty in tracking supply chains. The U.S. Labor Department lists Congolese cobalt as a product it has reason to think is produced by child labor.

Concern about how cobalt is mined “comes to the fore every now and again,” said Guy Darby, a veteran cobalt analyst with Darton Commodities in London. “And it’s met with much muttering and shaking of the head and tuttering — and goes away again.”

In the past year, a Dutch advocacy group called the Center for Research on Multinational Corporations, known as SOMO, and Amnesty International have put out reports alleging improprieties including forced relocations of villages and water pollution. Amnesty’s report, which accused Congo DongFang of buying materials mined by children, prompted a fresh wave of companies to promise that their cobalt connections were being vetted.

But the problems remained starkly evident when Post journalists visited mining operations in Congo this summer.

Digger Sidiki Mayamba, left, puts on his shoes in the room he shares with wife Ivette Mujombo Tshatela and their 2-year-old son, Harold Muhiya Mwehu, in Kolwezi, Congo, in June. “Creuseurs,” or diggers, work in the mine at Kawama. The cobalt that is extracted is sold to a Chinese company, Congo DongFang Mining.

In September, Chen Hongliang, the president of Congo DongFang parent Huayou Cobalt, told The Post that his company had never questioned how its minerals were obtained, despite operating in Congo and cities such as Kolwezi for a decade.

“That is our shortcoming,” Chen said in an interview in Seattle, in his first public comments on the topic. “We didn’t realize.”

Chen said Huayou planned to change how it buys cobalt, had hired an outside company to oversee the process and was working with customers such as Apple to create a system for preventing abuse.

But how such serious problems could persist for so long — despite frequent warning signs — illustrates what can happen in hard-to-decipher supply chains when they are mostly unregulated, low price is paramount and the trouble occurs in a distant, tumultuous part of the world.

Amount of cobalt in different devices

SMARTPHONE

5 to 10 grams

(as heavy as 2 to 4 pennies)

LAPTOP

1 ounce

(a slice of bread)

TYPICAL ELECTRIC CAR

10 to 20 pounds

(2 to 3 gallons of milk)

Lithium-ion batteries were supposed to be different from the dirty, toxic technologies of the past. Lighter and packing more energy than conventional lead-acid batteries, these cobalt-rich batteries are seen as “green.” They are essential to plans for one day moving beyond smog-belching gasoline engines. Already these batteries have defined the world’s tech devices.

Smartphones would not fit in pockets without them. Laptops would not fit on laps. Electric vehicles would be impractical. In many ways, the current Silicon Valley gold rush — from mobile devices to driverless cars — is built on the power of lithium-ion batteries.

But this comes at an exceptional cost.

“It is true, there are children in these mines,” provincial governor Richard Muyej, the highest-ranking government official in Kolwezi, said in an interview. He also acknowledged problems with mining-related deaths and pollution.

But, he said, his government is too poor to tackle these issues alone.

“The government is not a beggar,” Muyej said. “These companies have an obligation to create wealth in the area where they operate.”

Companies are unlikely to abandon Congo, for a simple reason: The world needs what Congo has.

Chen said he expected controversy surrounding how cobalt is mined in Congo to ripple far beyond Huayou Cobalt.

“This issue, I believe, we are not the only ones,” he said. “We believe there are many companies in similar situations as us.”

‘LUNGS OF THE CONGO’

The worst conditions affect Congo’s “artisanal” miners — a too-quaint name for the impoverished workers who mine without pneumatic drills or diesel draglines.

This informal army is big business, responsible for an estimated 10 to 25 percent of the world’s cobalt production and about 17 to 40 percent of production in Congo. Artisanal miners alone are responsible for more cobalt than any nation other than Congo, ranking behind only Congo’s industrial mines.

The industry should be a boon for a country that the United Nations ranks among the least developed. But it hasn’t worked out that way.

“We are challenged by the paradox of having so many resource riches, but the population is very poor,” Muyej said.

Kolwezi is a remote city steeped in cobalt and copper, which are often found together. It is sometimes called the “Lungs of the Congo” because of its economic importance.

The city sits along a two-lane highway best known for carrying tractor-trailers laden with minerals as they hurtle for the border with Zambia 250 miles away.

Then it’s on to seaports in Tanzania or South Africa.

From there, most of the cobalt floats by ship to Asia, home to the vast majority of the world’s lithium-ion battery manufacturing.

About 90 percent of China’s cobalt originates in Congo, where Chinese firms dominate the mining industry.

The cobalt begins its journey at a mine such as Tilwezembe, a former industrial site turned artisanal operation on the outskirts of Kolwezi where hundreds of men scour the earth with hand tools.

These men call themselves “creuseurs,” French for “diggers.” They toil inside dozens of holes pockmarking the mine’s moonscape-like bottom. The tunnels are dug by hand and burrow deep underground, illuminated only by the toylike plastic lamps strapped to the miners’ heads.

During a visit in June, the scene looked preindustrial. Dozens of diggers were at work, but the only sound was the occasional muffled clink of metal on stone.

“We are suffering,” said one digger, Nathan Muyamba, 29. “And our suffering is for what?”

‘LA FLEUR DU COBALT’

Diggers don’t have mining maps or exploratory drills.

Instead, they rely on intuition.

“You travel with the faith believing that one day you can find good production,” said digger Andre Kabwita, 49.

Nature is said to be one guide. Yellow wildflowers are considered a sign of copper. A plant with tiny green flowers carries the telling name “la fleur du cobalt.”

With few formal sites to claim for themselves, artisanal miners dig anywhere they can. Along roads. Under railroad tracks. In back yards. When a major cobalt deposit was discovered a few years ago in the dense neighborhood of Kasulo, diggers tunneled right through their homes’ dirt floors, creating a labyrinth of underground caves.

Other diggers wait until dark to invade land owned by private mining companies, leading to deadly clashes with security guards and police.

The diggers are desperate, said Papy Nsenga, a digger and president of a fledgling diggers union.

Pay is based on what they find. No minerals, no money. And the money is meager — the equivalent of $2 to $3 on a good day, Nsenga said.

Diggers gather at the Tilwezembe cobalt mine outside Kolwezi. Miners make an average of $2 or $3 a day. A fistful of cobalt-laden dirt is held up at the Musompo mineral market, where diggers sell their cobalt at small shops known as “comptoirs.”

“We shouldn’t have to live like this,” he said.

And when accidents occur, diggers are on their own.

Last year, after one digger’s leg was crushed and another suffered a head wound in a mine collapse, Nsenga was left to raise the hundreds of dollars for treatment from other diggers. The companies that buy the minerals rarely help, Nsenga and other diggers said.

Deaths happen with regularity, too, diggers said. But only mass casualties seem to filter out to the scant local media, such as the U.N.-funded Radio Okapi. Thirteen cobalt miners were killed in September 2015 when a dirt tunnel collapsed in Mabaya, near the Zambia border. Two years ago, 16 diggers were killed by landslides in Kawama, followed months later by the deaths of 15 diggers in an underground fire in Kolwezi.

In Kolwezi, a provincial mine inspector frustrated by a recent run of accidents agreed to talk to The Post on the condition that he not be identified, because he was not permitted to talk to the media.

He met the journalists in a minibus — jumping in, closing the door and taking a seat in the middle, far from the tinted windows so no one on the street could see him.

That morning, he said, he had helped rescue four artisanal miners nearly overcome by fumes from an underground fire in Kolwezi. The day before, two men had died in a mining tunnel collapse, he said.

He said he had personally pulled 36 bodies from local artisanal mines in the past several years. The Post was not able to independently verify his claims, but they echoed stories from diggers about the frequency of mining accidents.

The inspector blamed companies such as Congo DongFang that buy the artisanal cobalt and ship it overseas.

“They don’t care,” he said. “To them, if you bring them minerals and you’re sick or hurt, they don’t care.”

Congo DongFang responded that it had incorrectly assumed that these issues were the concern of its trading partners, who buy the cobalt from the miners and pass it on to the mining company.

CHILD LABOR

No one knows exactly how many children work in Congo’s mining industry. UNICEF in 2012 estimated that 40,000 boys and girls do so in the country’s south. A 2007 study funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development found 4,000 children worked at mining sites in Kolwezi alone.

Local government officials say they lack the resources to address the problem.

“We have a big challenge with the children, because it is difficult to take them out of the mines when there are no schools for these children to go to,” said Muyej, the provincial governor. “We have to find a solution for this.”

While officials and diggers acknowledge the problem of child labor, it remains a sensitive topic. Children work not just in underground mines, in violation of Congo’s mining code, but also on the fringes of the cobalt trade.

Guards prevented Post journalists from visiting areas where, according to local diggers, children often can be found working. At one point, The Post saw a boy in a red sweatshirt struggling to carry a half-full sack of mineral rocks. Another boy in a black soccer jersey ran up to help. Kabwita, the digger, watched them.

“They are just 10 or 12,” he said.

The Post also gave an iPhone to a digger to capture video of how women and children wash cobalt ores together.

One of these children is Delphin Mutela, a quiet boy who looks younger than his 13 years.

When he was about 8, his mother began taking Delphin with her on her trips to the river to clean cobalt ores. Washing minerals is a popular job for women here. At first, Delphin was tasked with keeping an eye on his siblings.

But he learned to distinguish the loose mineral pieces that fell into the water during washing.

Copper carried a hint of green.

Cobalt looked like dark chocolate.

If he could collect enough bits, he could get paid, maybe $1.

“The money I get I use to buy notebooks and so I can pay school fees,” Delphin said.

His mother, Omba Kabwiza, said this is normal.

“There are many children there,” she said. “That’s how we live.”

SKYROCKETING DEMAND

Cobalt is the most expensive raw material inside a lithium-ion battery.

That has long presented a challenge for the big battery suppliers — and their customers, the computer and carmakers. Engineers have tried for years to craft cobalt-free batteries. But the mineral best known as a blue pigment has a unique ability to boost battery performance.

The price of refined cobalt has fluctuated in the past year from $20,000 to $26,000 a ton.

Worldwide, cobalt demand from the battery sector has tripled in the past five years and is projected to at least double again by 2020, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

This increase has mostly been driven by electric vehicles. Every major automaker is rushing to get its battery-powered car to market. Tesla’s $5 billion battery factory in Nevada, known as the Gigafactory, is ramping up production. Daimler aims to open a second battery plant in Germany soon. LG Chem makes batteries for General Motors at a plant in Holland, Mich. Chinese company BYD is working on huge new battery plants in China and Brazil.

While a smartphone battery might contain five to 10 grams of refined cobalt, a single electric-car battery can contain up to 15,000 grams.

As demand has grown, so has artisanal cobalt’s importance in global markets. That became clear to everyone in the battery world two years ago, said Kurt Vandeputte, vice president of the rechargeable-battery materials unit at Belgium-based Umicore, one of the world’s largest cobalt refiners.

Cobalt demand for lithium-ion batteries is expected to double by 2025

The cobalt price was falling, even as battery demand shot up. The price of lithium, another key battery material, was skyrocketing.

“It got so clear that artisanal mining was taking a big place in the supply chain,” Vandeputte said, adding that Umicore buys only from industrial mines, including mines in Congo.

Artisanal cobalt is usually cheaper than product from industrial mines. Companies do not have to pay miners’ salaries or fund the operations of a large-scale mine.

With cheap cobalt flooding the market, some international traders canceled contracts for industrial ores, opting to scoop up artisanal ones.

“Everyone knew something was going on,” said Christophe Pillot, a battery consultant at Avicenne Energy in France.

At the same time, companies face growing scrutiny of their supply chains.

Consumers demand accountability; companies respond with promises of “ethical sourcing” and “supply chain due diligence.”

One result of this increased scrutiny can be found in Congo.

In 2010, the United States passed a conflict-minerals law to stem the flow of money to Congo’s murderous militias, focusing on the artisanal mining of four minerals.

But this same diligence is not required when it comes to cobalt.

Children gather along the principal highway linking Kolwezi and Lubumbashi. Diggers wait to be paid at the Tilwezembe cobalt mine. The prices, based on weight and content, are written on a burlap sign.

While cobalt mining is not thought to be funding wars, many activists and some industry analysts say cobalt miners could benefit from the law’s protection from exploitation and human rights abuses. The law forces companies to attempt to trace their supply chains and opens up the entire route to inspection by independent auditors.

But while Congo is a minor supplier of the four designated conflict minerals, the world depends on Congo for cobalt.

Analyst Simon Moores at Benchmark said he thinks this is one reason that cobalt has so far been excluded.

Any crimp in the cobalt supply chain would devastate companies.

‘WE SELL THIS TO THE CHINESE’

For most artisanal miners in Kolwezi, the global supply chain begins in a marketplace called Musompo.

The 70 or so small shops, known as “comptoirs,” are stacked cheek by jowl along the highway that leads to the border. Shop names are painted on cement walls: Maison Saha, Depot Grand Tony, Depot Sarah. Each shop has a handwritten board listing the going rate for cobalt and copper.

At a shop named Louis 14, the price list offered the equivalent of $881 for a ton of 16 percent cobalt rock. Rock with 3 percent cobalt was worth $55.

Nearby, minibuses pulled up with white sacks of freshly mined cobalt to sell. More sacks arrived on bicycles loaded down like pack animals.

Each load was tested by a radar-gun-like device called a Metorex, which detects mineral content. Some of the miners said they do not trust the machines, believing them to be rigged, but they have no alternative. Muyej, the governor, said he was looking for funds to buy a Metorex machine so diggers could independently test their minerals. There are many shops in Musompo, but diggers said the shops sold to the same company: Congo DongFang Mining.

“We sell this to the Chinese, and then the Chinese take it to CDM,” said Hubert Mukekwa, a shop worker shoveling cobalt.

An Asian man working at a “comptoir,” or counter, shop calculates a payment as “creuseurs,” or diggers, eagerly look on at the Musompo market.

In Congo, it is illegal for foreigners to own a comptoir. But not a single shop visited by Post journalists appeared to be run by Congolese. Asian men operated the Metorex machines. They punched up the tallies on oversize calculators. They handled the cash — thick wads of Congolese francs. And they often could be seen sitting in the back while Congolese men carried the 120-pound sacks. None of the comptoir bosses would talk to The Post.

Mukekwa finished filling up one sack.

“Once we have enough stock to take it to CDM,” he said, “we take it there.”

He pointed at a large blue-walled compound in the distance.

At a comptoir named Boss Wu, two Congolese workers, in jumpsuits with CDM printed in block letters on the back, stood watching other men loading cobalt sacks onto a truck.

Later, The Post witnessed an orange truck loaded with cobalt sacks pulling away from Musompo and onto the main highway.

“C24” was painted in blue on the truck’s cab. The Post followed C24 two miles up the highway, where it turned onto a dirt road running next to a tall brick wall. The truck continued on the road until it reached an entrance with armed guards and turned inside.

The facility with big blue walls was clearly marked CDM.

It was at these same gates that CDM says its inspection of its supply chain had stopped, never extending to the mines or marketplace, said Chen, the president of Huayou Cobalt, the parent company of CDM.

“We, in fact, didn’t know that much” about who they bought cobalt from, Chen said. “Now, we do due diligence.”

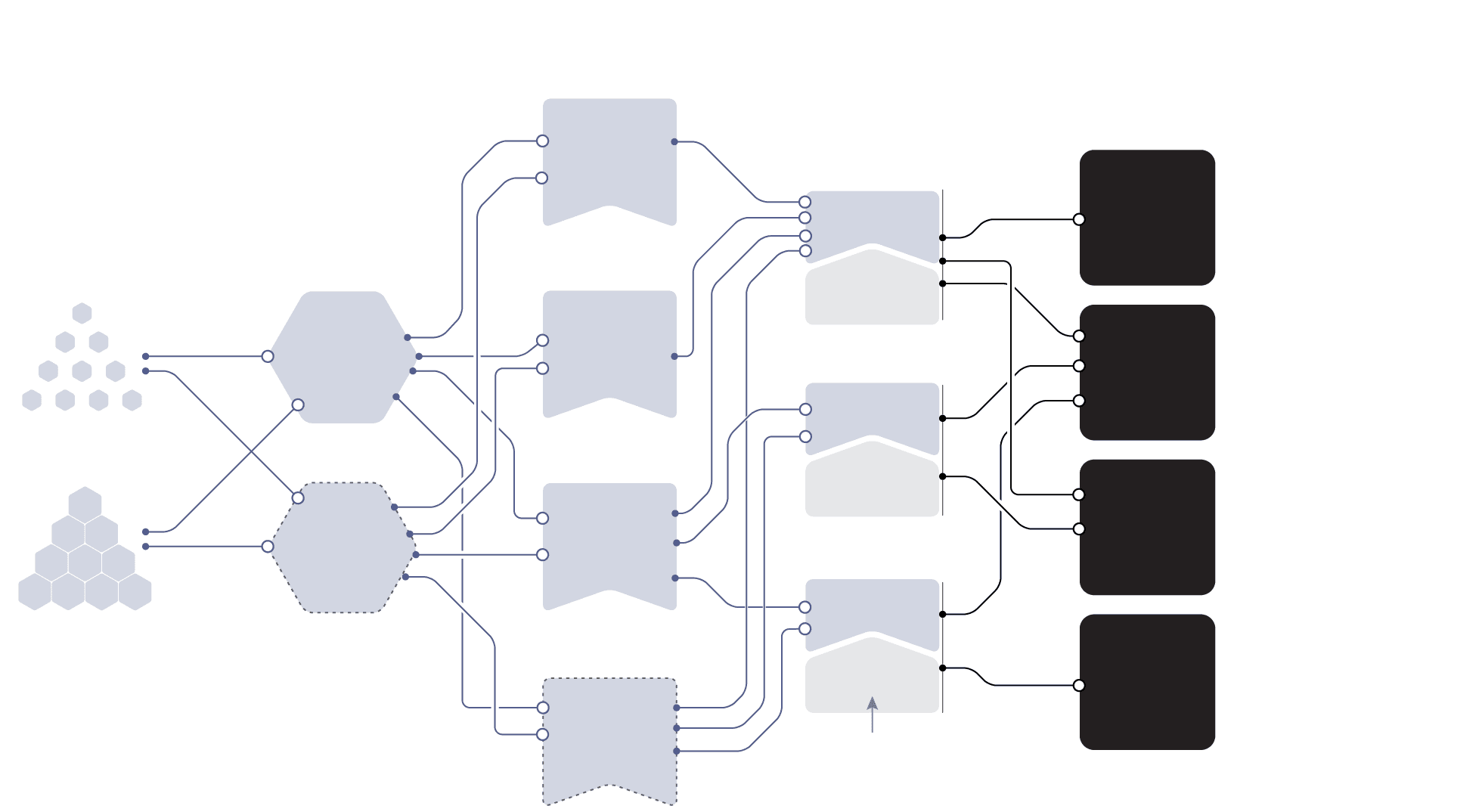

Tracing your battery’s cobalt

The lithium-ion battery industry has a massively complicated supply chain. Each consumer company has dealt with multiple suppliers — and their suppliers have dealt with multiple suppliers. This shows some of the connections within the industry. See companies’ responses to Washington Post’s investigation.

BATTERY MANUFACTURERS

CATHODE

MANUFACTURERS

They build batteries from cathodes, anodes and electrolyte solutions, all sourced from different companies.

Pulead

CON

WHAT THE COMPANIES SAY

Companies, in response to The Post’s questions, sounded equally uncertain about their cobalt supply chain, illustrating how little is known about the sources of raw materials.

But expectations are different today, said Lara Smith of Johannesburg-based Core Consultants, a firm that helps mining companies with this problem.

“Companies can’t claim ignorance,” Smith said. “Because if they wanted to understand, they could understand. They don’t.”

Last year, CDM reported exporting 72,000 tons of industrial and artisanal cobalt from Congo, making it No. 3 on the list of the country’s largest mining companies, according to Congolese mining statistics.

And CDM is by far Congo’s top exporter of artisanal cobalt, according to analysts and the company.

CDM ships its cobalt to its parent company, Huayou, in China, where the ore is refined. Among Huayou’s largest customers are battery cathode makers Hunan Shanshan, Pulead Technology Industry and L&F Material, according to financial documents and interviews.

These companies — which also buy refined minerals from other companies — make the cobalt-rich battery cathodes that play a critical role in lithium-ion batteries. These cathodes are sold to battery makers, including companies such as Amperex Technology Ltd. (ATL), Samsung SDI and LG Chem.

All of these battery makers supply Apple, providing power for iPhones, iPads and Macs.

Apple said its investigation revealed that its batteries from LG Chem and Samsung SDI contain cathodes from Umicore, which may contain cobalt from Congo but not from CDM. Apple said it thought its suspect cobalt was contained in ATL batteries with Pulead cathodes.

“I think the risks can be managed,” Pulead chief executive Yuan Gao told The Post, adding that he believes “the increased awareness is actually working, as everyone is monitoring everyone else along the supply chain.”

ATL also has supplied battery cells found in some Amazon Kindles, according to analysis by IHS, the global information company. ATL declined to comment.

Amazon.com, the company founded by Post owner Jeffrey P. Bezos, did not directly answer The Post’s questions about potential connections to suspect cobalt. The company issued a statement, reading in part: “We work closely with our suppliers to ensure they meet our standards, and conduct a number of audits every year to ensure our manufacturing partners are in compliance with our policies.”

Samsung SDI, which supplies batteries for Samsung, Apple and automakers such as BMW, said that its own ongoing investigation “has not shown any presence” of suspect cobalt, although it does use cobalt from Congo.

Samsung, the phonemaker, provided The Post with a statement saying that it takes supply-chain issues seriously but not addressing a potential connection to CDM. Samsung buys batteries for its phones from Samsung SDI and ATL, among others, according to industry data.

BMW acknowledged that some of the cobalt in its Samsung SDI batteries comes from Congo but said The Post should ask Samsung SDI for more details.

LG Chem, the world’s largest supplier of electric-car batteries, said the company it buys cathodes from, L&F Material, stopped using Congo-sourced cobalt from Huayou last year. Instead, it said, Huayou now supplies L&F Material with cobalt mined from the South Pacific island of New Caledonia. As proof, LG Chem provided a “certificate of origin” for a cobalt shipment in December 2015 for 212 tons.

But two minerals analysts were skeptical that LG Chem’s cathode supplier could switch from Congo cobalt to minerals from New Caledonia — or, at least, do so for long. LG Chem consumes more cobalt than the entire nation of New Caledonia produces, according to analysts and publicly available data. L&F Material did not respond to repeated requests for comment. When The Post asked LG Chem to “respond to claims that the numbers don’t add up,” LG Chem did not answer the question directly, responding that it checks certificates of origin on a routine basis.

LG Chem also runs a Michigan battery plant for one of its biggest customers, GM, which plans to start selling its electric Chevrolet Bolt later this year. LG Chem said the Michigan plant has never received Congolese cobalt.

Another LG Chem customer, Ford Motor, said it has been told by LG Chem that Ford batteries have no history of CDM cobalt.

Most Tesla models use batteries from Panasonic, which buys cobalt from Southeast Asia and Congo. Replacement batteries for Tesla are manufactured by LG Chem. Tesla told The Post it knows LG Chem’s Tesla batteries do not contain Congolese cobalt, but it did not say how it knows this.

Tesla, more than any other automaker, has staked its reputation on “ethically sourcing” every piece of its celebrated vehicles.

“It is something we do take very seriously,” Kurt Kelty, Tesla’s director of battery technology, said in March at a battery conference in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “And we need to take it even more seriously. So we are going to send one of our guys there.”

Six months later, Tesla told The Post it is still working on sending someone to Congo.

BIRTH DEFECTS, ILLNESS

In Lubumbashi, another center of Congo’s mining industry, 180 miles from Kolwezi, doctors have begun to unravel what has long been a mystery behind a range of health problems for local residents.

Their findings point to the mining industry as the problem.

These doctors at the University of Lubumbashi already know miners and residents are exposed to metals at levels many times higher than what is considered safe.

One of their studies found residents who live near mines or smelters in southern Congo had urinary concentrations of cobalt that were 43 times as high as that of a control group, lead levels five times as high, and cadmium and uranium levels four times as high. The levels were even higher in children.

Another study, published earlier this year, found elevated levels of metals in the mining region’s fish. A study of soil samples around mine-heavy Lubumbashi concluded the area was “among the ten most polluted areas in the world.”

Now the doctors are working to connect the dots.

“We are trying to draw a line between disease and metals,” said Eddy Mbuyu, a university chemist.

But they are cautious about their task.

“The mining business has the money, and that money means power,” said Tony Kayembe, an epidemiologist at the university’s hospital.

Current studies are looking at thyroid conditions and breathing problems. But doctors are most concerned by possible connections to birth defects. One study the university doctors published in 2012 found preliminary evidence of an increased risk of a baby being born with a visible birth defect if the father worked in Congo’s mining industry.

The Lubumbashi doctors also have issued reports on birth defects so rare — one is called Mermaid syndrome — that they are the only cases ever known in Congo. All occurred in children born in heavy mining regions.

For Kayembe, the study that stood out most looked at babies born with holoprosencephaly, a usually fatal condition that causes severe, distinctive facial deformities. It is almost unheard of. Entire medical careers pass without seeing one. But last year, doctors in Lubumbashi recorded three cases in three months.

“This is not normal,” Kayembe said.

These medical inquiries could bring some relief to residents such as Aimerance Masengo, 15, who has been blaming herself since giving birth last year to a baby boy with severe, fatal birth defects.

In a voice barely above a whisper, Aimerance recalled how she had been so scared when she saw her newborn. The doctor was scared, too, she said.

The doctor told Aimerance it was impossible to know for certain what went wrong. But, he noted, the baby’s father worked as a cobalt digger. He told Aimerance he had seen many problems in the children born to diggers.

Aimerance and the baby’s father lived in the nearby village of Luiswishi, home to 8,000 people. Everyone there seemed to be connected to artisanal mining. And in the past three years, according to local activists, four newborns from this tiny village have died of severe birth defects.

A child throws a stone into the Kapolowe River outside Lubumbashi. Environmentalists, doctors and activists say that the region’s rivers suffer from severe pollution that they think is from the copper and cobalt mining throughout the area. Catfish caught in the Kapolowe River is offered to prospective customers near the river’s banks. A study published this year showed elevated levels of metals in the mining region’s fish.

THE ‘CREUSEURS’ WAIT

For diggers such as Sidiki Mayamba, worried about affording flour for his family, the greatest concern is not safety or potential health problems. It is money. He needs the work. But he doesn’t want his 2-year-old son, Harold, to follow him into the mines.

“A digger is a hard job with many risks,” Mayamba said. “I cannot wish for my child to have this kind of job.”

Cleaning up the cobalt supply chain will not be easy for Huayou Cobalt, even with the support of a powerful company such as Apple.

But Chen, Huayou’s president, said it is the proper action, not only for the company but also for the Congolese miners.

“Some companies just want to get away from the problem,” Chen said. “But Congo’s problem is still there. The poverty is still there.”

The question is whether Huayou’s other customers, after years of buying cheap cobalt with no questions, will be supportive.

Pyers, the Apple senior director, said the company does not want to take steps aimed at just “making the supply chain look pretty.”

“If we all cut and run from the Democratic Republic of Congo, it would leave the Congolese people in a devastating position,” Pyers said. “And we will not be a party to that here.”

Starting next year, Apple will internally treat cobalt like a conflict mineral, requiring all cobalt refiners to agree to outside supply-chain audits and conduct risk assessments.

Apple’s action could have major repercussions throughout the battery world. But change will be slow. Apple spent five years working to certify that its supply chain was free of conflict minerals — and that action was enforced by law.

None of these efforts change the fate of diggers such as Kandolo Mboma.

At the Tilwezembe mine this summer, Mboma sat on a boulder, seemingly catatonic, his blue jeans stained black, his bare feet dangling just above the red dirt. His eyes failed to register the other diggers filing past.

“He was working all night, and he has not eaten,” a fellow digger said.

Mboma, 35 and a father of three, was waiting for his cobalt to be weighed. Then, he hoped, he would get paid.

He sat next to a series of small food stalls, stout squares of discarded mining sacks stretched over sticks, where a digger could buy a bread roll for 100 Congolese francs, equal to about 10 cents. The bread came with a free cup of water.

“You eat what you make,” Mboma said finally.

And eating would have to wait.

A “creuseur” descends into a tunnel at the mine in Kawama. The tunnels are dug with hand tools and burrow deep underground.

Some resources and graphics could not be loaded here, please see the original report here for all interactive media, videos and graphics.