Emerging Market Perspectives on Business and Human Rights Measures and Economic Development

Business and Human Rights (BHR) measures for companies and investors have developed significantly over the last few years, from voluntary principles to mandatory regulations – to varying degrees in different contexts. In parallel, donor approaches to inclusive economic development have evolved towards greater emphasis on the role of business, market access and investment in emerging economies to create decent jobs, livelihoods and growth. Both have the potential to promote the realisation of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8: to promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

BHR regulations aim at raising standards, through means such as excluding imports or placing responsibilities on companies to ensure that BHR principles are upheld across the supply chain. BHR voluntary standards seek to encourage changes to business behaviour, and provide positive choices for consumers, businesses, government procurement and investment markets. Together, such measures underpin efforts to identify, prevent, mitigate, and remediate human rights abuses, while many also seek to enable businesses to have a positive impact on jobs and livelihoods, families and communities throughout value chains.

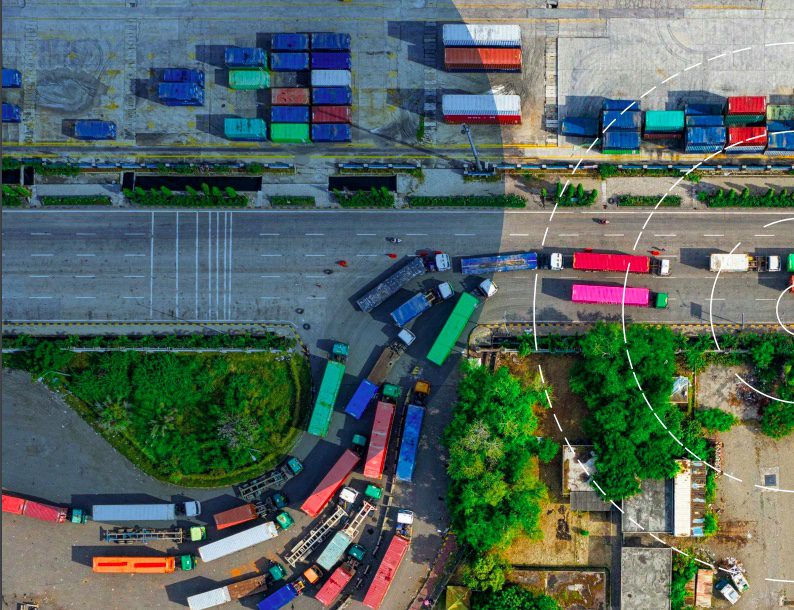

Intersecting factors can create barriers to achieving positive human rights and development outcomes through BHR measures – especially in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs). The nature of global commodity value chains creates challenges for cascading BHR measures to all levels of the supply chain, as well as for transparency and traceability efforts to monitor their implementation.

This is particularly the case where informal sectors form large parts of the national economy and/or where their place in supply chains is unclear. This makes it especially difficult to detect or address human rights abuses. Sub-Saharan Africa has the largest share (85 per cent) of the population engaged in informal labour1 , with informal crossborder trade accounting for 30-40 per cent of trade in the region.2 This creates clear challenges for adhering to BHR measures, leading to reduced chances of securing critical access to global markets. Lost market opportunities can result in lower incomes, contributing to cycles of poverty, cultural norms and a lack of access to quality education which all increase vulnerability to human rights abuses and violations, including modern slavery and the worst forms of child labour.

The impacts, complexities and unintended consequences of BHR measures are best understood from the perspective of those most affected by them. This research sought to identify how the implementation of BHR measures are experienced in EMDEs through a series of firsthand accounts. The research involved consultations with 118 individuals in Kenya, Ghana and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). These individuals represent a broad range of stakeholders including producers and suppliers, processing companies, traders, industry organisations, investors, community organisations, civil society, local government and trade unions. Findings from the DRC build on existing research from the four year Partnership Against Child Exploitation (PACE) programme.

For most participants, taking part in this research was the first time they had been asked about their experience of implementing BHR measures, as well as their perspective on what is working or not from efforts to-date. Stakeholder perspectives are increasingly drawn upon in the development of BHR measures (such as the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive or CSDDD) in order to try to ensure they are fit for purpose and avoid unintended consequences. However, the research found a need for a stronger bottom-up approach to creating and implementing BHR measures. Regulations have been criticised due to power imbalances in the supply chain between the top and the bottom as well as between buying and production countries. For example, while there is an inherent expectation in regulations that buyers, donors and governments in regulated markets should bear most of the responsibility for resourcing implementation of BHR measures, much of the resource burden ultimately falls to EMDE companies and other upstream stakeholders.

In many contexts, the research produced evidence that BHR measures do lead to greater respect for human rights. In DRC, for example, BHR traceability measures have contributed to reducing conflict at some mineral sites and have, to some extent, helped reduce the presence of children working on dangerous tasks. The research went beyond this, however, to obtain views on the balance between positive impacts, challenges and unintended consequences – for example in DRC where alongside desired outcomes, unintended consequences for jobs and livelihoods were also clearly highlighted. The experiences reported, and the recommendations made are invaluable for development and implementation of new BHR measures, guidance, interventions and future policy developmen