Eight-seven-five. Angel still remembers her number, months after leaving the UK. The number assigned to her by the farm. The number used instead of her name when her supervisor ordered her to work faster or punished her.

Angel, a single mother from South Africa, said that she felt like a prisoner, being shouted at and undermined constantly, no matter how hard she worked. Her name and the real number she was called by have been changed to protect her identity.

“Even before we start work the supervisors would be screaming at us… they would treat you like an animal,” she said.

Last year, during the hottest summer on record, Angel and hundreds of other workers on Dearnsdale fruit farm in Staffordshire were told to pick and sort about 100-150kg of strawberries every day inside polytunnels designed to trap heat. It was so hot that at least one worker fainted, she said. The strawberries they picked ended up on the shelves of some of the UK’s largest supermarkets, including Tesco, Co-op and Lidl.

An investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and VICE World News has uncovered widespread mistreatment of migrants working at more than 20 UK farms, nurseries and packhouses in 2022. Workers reported a litany of problems, from not going to the toilet for fear of not hitting targets, to being made to work in gale-force winds. Some said they would be shouted at or punished for having their mobile in their pocket or talking to work colleagues while on the field. Others said they were threatened by recruiters with being deported or blacklisted.

Many were left in debt and destitution, and some left the UK being owed money by their employers. One worker even had to pull out his own tooth because he could not find appropriate medical care. Our findings expose a poorly enforced government visa scheme that is flagrantly breached by farms and recruiters, and which leaves people vulnerable to exploitation.

At Dearnsdale, those who made mistakes or failed to hit targets were routinely sanctioned. The most common punishment was to have their shift cut short – every day several workers would be sent back to their caravans after only a few hours’ work. That meant that on a day when a worker was hoping to earn money for eight hours of work, they would be paid for only three. The practice is common on farms using the visa scheme.

For workers like Angel, who took on debt to pay for visas and flights to come to the UK, having their earnings cut was devastating. Even after picking fruit and vegetables for five months, she still has not been able to pay off her £1,250 loan.

Dearnsdale said: “We do refer to members of staff by their numbers, however this is not to degrade the individual but purely on a business need basis as is standard in the industry.” On the issue of workers having their hours cut short, it said: “We are not aware that people are sanctioned in the manner suggested.” The farm added that it took allegations of bullying and the health and safety of workers seriously and was ‘upset’ to be made aware of the allegations. It said that it actively monitors temperature inside polytunnels and ensures that appropriate steps are taken to maintain worker safety in hot conditions. It also said it took “appropriate steps” in response to medical emergencies.

Professor Dame Sara Thornton, the former independent anti-slavery commissioner, said TBIJ’s findings intensified her concerns that indicators of forced labour are present on British farms.

With food shortages repeatedly hitting headlines in recent weeks, there is likely to be increased pressure from farmers to issue more visas for migrant workers, she said. But to her, our findings suggested that problems with the visas remain, more than a year after a government review said conditions were “unacceptable”.

Culture of fear

Before the UK’s departure from the European Union, the vast majority of the 55,000 casual seasonal workers in British agriculture came from Europe. The seasonal worker visa scheme was launched in 2019 to cover the gaps left by Brexit, but labour rights organisations have warned that the way the six-month visa is designed puts workers at risk of exploitation.

Workers are in the UK for a short period of time and can only work for farms that have contracts with their recruiter, so have difficulty leaving situations in which they feel exploited. Workers often take out loans to pay for the costs of coming to the UK, which means that they are less likely to speak out for fear of losing work and not being able to pay off their debts.

But pressure from the National Farmers Union, an industry association representing farm owners, has resulted in the government increasing the number of workers that come to the UK on the scheme by thousands each year. In 2023, up to 55,000 visas could be issued, up from just 2,500 in 2019.

While these workers are often talked about as a solution to the UK’s labour and potential food shortages, their voices rarely form part of the conversation. Even the government’s review of labour shortages is led by a panel made up mainly by food business executives, without a single worker representative.

In order to understand the reality of working under this scheme, TBIJ conducted interviews with nearly 50 workers who had come to the UK from Nepal, Kazakhstan and South Africa, among other countries, and analysed data from The Work Rights Centre, a charity that advocates for the rights of migrants, covering an additional 23 workers’ experiences.

While the work is always tough and physically demanding, some farms and supervisors treated workers significantly better than others. For many workers the scheme is an opportunity to earn far more than would be possible in their country of residence.

However, nearly half of the workers TBIJ interviewed described a culture of fear. Supervisors at some farms would shout at workers or order them to pick faster, while threatening to cut their shifts or hours if they failed to hit targets. Roughly the same proportion felt that complaints to farm managers or recruiters were ignored, or that it was difficult to make complaints. Some also said they faced discrimination.

One Ukrainian worker said that managers at a nursery in Worcestershire made them pull down polytunnels during Storm Eunice, the most powerful storm to hit the UK in decades. He feared for his life. At one point, as he was pulling down the plastic sheet with several other workers, a gust blew and swept them a foot into the air.

A worker from Nepal said that at a farm in Scotland, they were forced to line up outside every morning for as long as 15 minutes, even in the rain, until the manager arrived, without any explanation as to why they had to do this. Those who did not line up would be denied work.

Growing debts

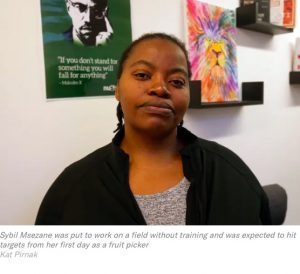

At about the same time Angel was starting her placement in Staffordshire, more South Africans were arriving at Tuesley Farm, Surrey, which supplies Tesco, Co-op and Waitrose. One of them was Sybil Msezane, 41, who decided to apply to work as a fruit picker in the UK when her work as a human rights consultant dried up during the COVID-19 pandemic. She had previously worked with trade unions in South Africa and was shocked to discover how few labour protections workers had in the UK.

“Slavery has been outlawed, but it still exists within the farm,” she said. “You can’t physically abuse people, but you can verbally abuse people and you can threaten them with their livelihood.”

From the first day, she said, she was put to work on the field without training and was expected to hit targets. While the visa scheme rules state that workers should be treated “fairly”, punishing workers who miss targets is widespread in farms across the country – workers told TBIJ of at least seven farms where this practice was common.

Like most soft fruit farms in the UK, Tuesley relies heavily on migrant workers. In 2017, Tuesley’s farm manager told Radio 4 that in the previous five years only one British person had worked on the farm, and had quit after one day.

Msezane said that in her first few weeks, she saw people crying as they returned from the fields. Two South African workers told TBIJ that they left the farm just weeks into the job after suffering bullying by supervisors and allergic reactions to the fruit they were picking that the farm did not address. One of them put in a detailed complaint to her recruiter, the charity Concordia, but never heard back.

Another worker at Tuesley, whose name we are withholding at her request, said that she couldn’t go to the toilet because she would miss targets; if she did not, she would get shouted at. “You get mentally, physically, and emotionally broken down,” she said. “The way they work with people I wouldn’t even do to my worst enemy. Then they tell you if you don’t want to work on these standards, you can go.”

Msezane said that she used the last of her savings to pay for her flights to the UK, but many of her compatriots approached loan sharks who charged as much as 70 percent in interest. This creates a system of “indentured servitude”, where workers are less likely to speak out for fear of being refused work and having their earnings cut, she said.

Tuesley Farm did not respond to a request for comment.

Some workers arrive in the UK with even bigger debts. Several Nepali workers told TBIJ that their flights and visa cost as much as £1,500. Some paid informal brokers more than £4,000, having been told it would guarantee them a place on the scheme.

While a culture of bullying and cutting shifts does not exist at every farm, workers at some farms still felt other kinds of financial pressures. Farmers often charge workers for accommodation, such as a small shared room in a caravan, and gas and electricity bills. Some also demand workers pay for their own bed linen – one farm charged £15 for a duvet and pillows – and pay £1 a go to use the washing machines. One worker said she even had to pay for transport to the fields. At least one farm, Gaskains in Kent, charged workers nearly £85 per week for a shared room in a caravan last year – more than the pay for eight hours of work. Gaskains said it complied with government caps on rent.

This is in sharp contrast with seasonal worker programmes in other countries, like the US, where flights and accommodation costs are covered by the farm, or Canada, where the cost of accommodation is capped at CA$30 (£18) per week.

Workers also have income tax deducted directly from their payslips, even though many will not earn enough in the six months they are in the UK to reach the £12,750 minimum taxable threshold.

A Waitrose spokesperson said: “Worker welfare is absolutely vital to us, and we’re really concerned to read these allegations. We’re looking into this with our supplier as a matter of urgency.”

Lidl and Co-op did not respond to requests for comment.

Tesco directed TBIJ and VICE World News to a statement by the British Retail Consortium, which said: “Protecting the welfare of people and communities in supply chains is fundamental to our members, and any practices that fall short of our high standards will not be tolerated. Our members are urgently reviewing the allegations raised by these workers, engaging with their primary suppliers to ensure a comprehensive investigation is undertaken.”

Lack of enforcement

The government has said that it is the responsibility of the recruiters who sponsor the workers’ visas to monitor and ensure their welfare. But in practice the scheme’s rules to ensure workers’ welfare are rarely enforced.

A report published last year by the independent chief inspector of borders and immigration found that even though workers told Home Office officials about poor treatment, discrimination, issues with accommodation and being obstructed from accessing healthcare, “no allegations were investigated by the Home Office, by scheme operators, or by other government organisations”. In one case, a Home Office compliance officer said a worker found it so hard to get healthcare that “he was in agony for about 4 hours and then he had to pull out his own tooth.” The report went on: “When serious concerns have been raised by workers themselves, [the Home Office] did not act promptly or seriously.”

The Home Office told TBIJ and VICE World News: “The welfare of visa holders is of paramount importance, including in the Seasonal Workers scheme, and we are clamping down on poor working conditions and exploitation … We will always take decisive action where we believe abusive practices are taking place.”

The government recently announced that from April 2023 it would stop requiring farms to pay seasonal workers above the minimum wage. But it also promised measures around safeguarding, including requiring farms to guarantee workers at least 32 hours of work per week.

Caroline Robinson, director of the Worker Support Centre, which helps seasonal workers in Scotland, fears that without adequate enforcement, guaranteed hours are unlikely to improve conditions for the workers who are most at risk of exploitation. She said: “The major problem left unaddressed with the seasonal worker visa scheme is the absence of targeted compliance activity by labour market enforcement bodies and an accessible complaints mechanism.”

Existing Home Office rules state that recruiters cannot “normally” refuse requests from workers to change employers, a vital safeguard that is supposed to ensure they are not left without work during the six months they are allowed to stay in the UK.

Yet, TBIJ found that some people were left without work for weeks or even months after being dismissed from a farm without being offered a new placement. Some people go back home after a few weeks because they can no longer afford to stay in the UK. Many end up thousands of pounds in debt. Others suck it up and burn through their cash until they get to the next farm. Thirty people told TBIJ and Work Rights Centre that they had difficulties getting transfers or were refused transfer requests by recruiters including AG Recruitment, Concordia and Pro-Force.

In the worst cases, workers who were brought to the UK at the end of the summer soft fruit picking season were told to return home just weeks after arriving.

In response to a Freedom of Information request, the Home Office said that more than 2,300 people on seasonal visas arrived in the UK in September 2022, as recruiters were apparently telling other workers they had to leave because there was no work available.

At least one recruiter, AG Recruitment, tried to force workers to leave the UK before their six months’ was up. In November, the company told several Nepali workers at Gaskains that there was no work available there or at any other farm, and went as far as threatening them with blacklisting if they did not leave the UK. At the same time, AG Recruitment was preparing to bring more Nepali workers to the UK.

Pro-Force did not respond to a request for comment, and Concordia declined to comment. AG Recruitment said: “Ensuring seasonal workers are treated fairly and respectfully is absolutely fundamental to who we are, what we do and how we do it” and that it “has not, cannot, and would not ever threaten workers to try and force them to leave the UK, not least because we do not have authority to do so”. Any refusal to transfer workers was because other placements were not available, it said. It added that “seasonal worker queries and grievances are always treated as a priority” and reported to the Home Office if necessary.

Since November, the company has had its licence to sponsor visas revoked, but remains a government-licensed recruiter.

Some workers were even threatened with deportation. Fikile Masuku, who came to the UK from South Africa in August, was told by Concordia that she had been reported to the Home Office as an absconder three months into her visa, even though she kept the recruiter informed of her whereabouts and had repeatedly asked them to give her more work.

Miljana Istokovic arrived from Serbia in September to work at Medlar Fruit Farm in Lancashire. Three weeks later she was dismissed, forcing her to get into £500 of debt to buy a return ticket home. She said that supervisors at the farm, which supplies Tesco and Lidl, would often shout or cut workers’ shifts if they briefly stopped picking, if they talked to colleagues or even if they had a phone in their pocket.

She waited in her caravan at Medlar for two weeks for her recruiter, Concordia, to transfer her to another farm. Eventually, her electricity was cut off, despite there being money left on the meter.

Medlar said the “welfare and happiness of our team is fundamental to us” and told TBIJ and VICE that they were investigating the claims, which they took “very seriously”.

Asked what she thought of the seasonal worker scheme, Istokovic replied: “They consider us cheap labour and worthless people.”