39 Vietnamese people died being smuggled into the UK in 2019. Most were from Nghe An province.

In late October 2019, ambulance crews in the United Kingdom were called to a scene of horror.

On a quiet road in a nondescript industrial park in Essex, the bodies of 39 people were found when the heavy steel doors of a refrigerated truck trailer were opened.

The victims had suffocated. Death came slowly as oxygen levels inside the airtight container depleted for the 28 men, eight women and three children as their attempt to be smuggled into the UK ended tragically.

The youngest were two 15-year-olds. All were from Vietnam and the majority were from one province – Nghe An.

“I’m sorry Dad and Mum,” 26-year-old Pham Thi Tra My tapped out in a final text message she composed for her parents.

“Mum, I love Dad and you so much. I’m dying because I can’t breathe … I am so sorry, Mum,” she wrote in a phone message that was widely reported on at the time.

The message was delivered long before her death was officially confirmed by police investigators in the UK.

In 2021, seven people were jailed in the UK for a total of 92 years for their role in the deaths of the 39. This week, an eighth suspect, described as a “right-hand man” in the smuggling ring, was sentenced to 12 years and seven months in prison by a UK court.

“Twenty-eight men, eight women and three children died agonising deaths … as a result of the conspiracy of which you were part,” Judge Neil Garnham told Marius Draghici, 50, as he handed down his sentence, the Reuters news agency reported.

As details emerged of the macabre discovery in Grays, Essex – approximately 35km (22 miles) from the centre of London – people smuggling operations received rare media attention. So, too, did the risks that many are willing to take for a chance at a better life.

The tragedy also briefly shone a spotlight on Vietnam’s north-central province of Nghe An, from where 21 of the 39 had journeyed to the UK.

With poor job prospects at home, large numbers of Vietnamese leave Nghe An in search of work opportunities overseas. This is not by chance. Local authorities have long promoted “labour export” and the policy has become so established in Nghe An that it appears that people are a key element of the province’s export plans.

On a recent visit to Nghe An, Al Jazeera spoke to locals who had mourned the dead from the Essex tragedy, but were making their own plans to work overseas – either legally or illegally. And while they were fully aware of the risks involved, they were also focused more on the potential rewards, which are visible to all living in Nghe An, particularly the residents of the “billionaire village”.

A typical teenager

Pham Thi Thanh Huyen may look like a typically shy teenager, but she does not talk like one. The 17-year-old speaks matter-of-factly about a bet she has placed on her future. A gamble with life that she is sure will pay off: Moving to South Korea as a migrant worker and earning money to send home to her family.

The South Korea idea has been with Huyen since she was 12 years old, she says. The eldest of three siblings, Huyen is already a housekeeper and carer for her younger brother and sister, as well as the primary caregiver for an aunt with disabilities.

Those domestic responsibilities are not so much by choice. Her mother works six days a week at a garment-making factory, and her father is employed in construction in Da Nang city, about 600km (373 miles) from the family’s home.

Huyen’s parents are doing everything to raise the money needed to send her to South Korea, which at a cost of some 300 million Vietnamese dong ($12,700) is an extraordinarily large sum for a rural family.

But the money is an investment in future returns in a business model that has thrived in Nghe An province.

“You see that little shabby house on the side?” Huyen asks, gesturing to a group of houses across a rice field from her home.

“They had that and then built that blue one next to it,” she says, indicating a modern, two-storey residence with blue roof tiles that stands out among the older, shabbier structures.

“I think the father went to Europe many years ago,” Huyen tells Al Jazeera, with the permission of her mother. Huyen’s little sister listens silently and closely nearby, hanging on every word uttered by her older sister.

Huyen knows of many people who have financed renovations for their family homes after migrating to South Korea for work and sending money back.

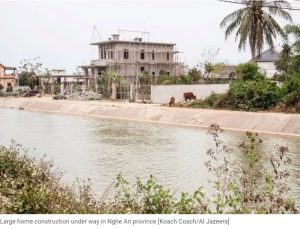

The proof is all around in the form of newer, larger houses built with worker remittances from near and far – from Europe and Australia to Laos, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea.

A relative who works in a labour brokerage company that facilitates sending Vietnamese workers to South Korea can help Huyen reach her dream, she says.

Paperwork required to apply for a South Korean visa, Korean language classes and a job in the service sector can all be arranged by her labour broker relative.

“I’m not afraid of migrating irregularly, but afraid of unreliable brokers,” she says, recounting the outpouring of grief near where she grew up in Nghe An on the day the remains of the victims of the Essex tragedy were returned to their homes.

For Huyen, what occurred in Essex was uncommon – an aberration.

She knows of three other people in her commune who migrated to Europe to find work and were able to send money home.

Now, Huyen is more than ready to leave Yen Thanh district, located about a 90-minute drive from the birthplace of the father of the nation – Ho Chi Minh.

Nghe An is revered in Vietnam’s revolutionary history as the birthplace of Ho Chi Minh, who led the country’s independence struggle against France and would later fight both South Vietnam and the US military that propped up successive regimes in then-Saigon.

Defeating the US and reunifying the country in 1975, Vietnam’s economy has thrived in recent decades, though not everywhere and not equally.

A combination of few local opportunities and inducements by labour brokers to become migrant workers has transformed the landscape in Nghe An – a province dominated by agricultural land where modest homes such as Huyen’s are sandwiched between vast expanses of paddy fields and interlinking canals.

Labour brokers lobby in the province’s high schools, promoting overseas work for most and study abroad schemes for some who can afford it.

Brokers target students in their senior year, Huyen says, because they are often at a crossroads in life between hoping to enter university or migrating overseas. State media has also reported on the trend in recent years of young people in many villages in Nghe An and neighbouring Ha Tinh province graduating high school just so they can migrate for work overseas.

But the export of people as labour has left families in Nghe An scattered, led generations to contemplate the life of foreign migrant workers, and some who mourn the loved one that will never return home – such as the families of the 21 young people from Nghe An who were found dead in an Essex truck container.

‘No language required, long-term visa, high incomes’

The impact of a migrant labour on Nghe An is palpable in the provincial capital, Vinh.

A modern city in the making, Vinh’s budding commercial sector and physical infrastructure mirrors Vietnam’s major cities of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

Vinh is a small, vibrant city with Instagrammable cafés attracting a millennial and Gen Z clientele. Cars far outnumber motorbikes in this city, an unusual phenomenon not just for Vietnam generally but for a province with one of the lowest per-capita annual incomes in the country. The abundance of cars is largely attributed to financial remittances from Vietnamese working overseas, as is the wealth on display among customers at Vinh’s Lotte Mart convenience stores, the CGV cinema and the Korean BBQ chain Gogi.

Remittances sent by Nghe An natives working in Asia, Europe and North America have buoyed the economic profile of the province, where 13 investment projects – valued at more than seven trillion dong ($296m) – and focused in the tourism and entertainment sectors, education, manufacturing and real estate are due to finances sent from Vietnamese working overseas. The province is also home to industrial zones with significant foreign direct investment.

Labour brokerage firms dot Vinh city with their signs advertising life-changing opportunities overseas. Ads are posted online and invitations to prospective overseas workers are posted in closed and public forums and social media groups.

“No languages required, long-term visa, high incomes”, declared one such sign advertising recruitment for jobs in Slovakia, or “old Czechoslovakia” as the signage points out.

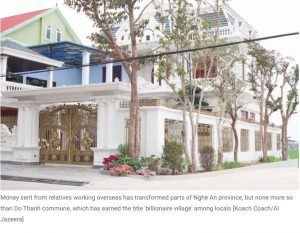

It is common among families in Nghe An for the elderly and young to take care of each other while those of working age leave for overseas or Vietnam’s larger cities. People are comfortable discussing their migrant labour experience, whether about family members, acquaintances, or themselves, and also point you in the direction of Do Thanh commune, known locally as “billionaire village”.

In Do Thanh, imposing villas with elaborately designed ornate metal gates dominate the neighbourhood. Dozens of luxurious homes with multicar families are threaded through the fabric of life in this rural commune. The aspirations the neighbourhood gives rise to are embedded in the minds of younger generations, such as Huyen’s.

A property in “billionaire village” viewed by Al Jazeera consisted of a multi-level white villa with the outline of a lion moulded into an ornate gated entrance. Parked out front was a luxury model Lexus car, which retails new in Vietnam at about $340,000, with a personalised licence plate comprising five identical numbers – a desirable and auspicious addition to Vietnamese vehicles that commands a hefty price.

A resident of the house said only that a younger brother had been working in the UK for years.

Pham Gia Ngan, a Nghe An native who currently lives in Hanoi, explained that building a new house for family is a priority for people from his province.

“There is this thing,” Ngan said. “Whenever we [Nghe An people] have money, we will build a house first, before anything else,” he told Al Jazeera.

But the thread of luxury running through Vinh and Do Thanh only stretches so far.

The further one travels from Vinh and “billionaire village” the clearer the wealth gap between the capital city and the province’s towns and communes becomes – decades after the Vietnamese government adopted the promotion of migration labour as a policy.

Vietnam’s ‘labour export’ policy

In 1980, the post-war and cash-strapped communist government in Hanoi adopted a policy of actively encouraging and sending Vietnamese people to friendly countries in the then-Soviet Union as migrant labour.

That was just five years after the end of the war, and the initiative helped to alleviate unemployment domestically and brought remittances back to grateful relatives in Vietnam.

Almost three decades on, in 2009, Vietnam’s then-Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung implemented a “labour export” policy known as Programme 71, which focused on alleviating poverty in 62 districts in 20 provinces, including Nghe An.

The policy offered incentives, such as low-interest loans and state-funded training, to facilitate Vietnamese travelling overseas to work in countries such as Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Macau, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The majority of Vietnamese labour migrants come from the north and north central region of the country – where Nghe An is located, and according to a Nghe An provincial state media report in March, remittances attributed to Vietnamese working on contracts overseas were valued at half a billion dollars annually for the province.

Such inflows of cash have contributed to putting Vietnam in 10th place among the largest remittance-receiving countries in the world.

And for five consecutive years to 2016, Nghe An sent more migrant workers abroad than any other locality in Vietnam, according to a study by the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

But the IOM report also said gaps in regulatory oversight of labour recruitment agencies, coupled with limited administrative and criminal law enforcement, allowed unethical recruitment practices to thrive, putting migrant workers at risk of forced labour and human trafficking.

Tran Minh Khanh experienced this firsthand.

The 34-year-old Nghe An native was one of about 500 workers involved in a high-profile migrant worker abuse case in Serbia in 2021 that drew international media attention.

Hired to work in Serbia building a tyre factory for a Chinese conglomerate, the workers had their passports confiscated and regularly had their wages withheld while dealing daily with long hours toiling in cold conditions and living in substandard accommodations.

Some of the workers sent to Serbia were allegedly duped into paying thousands of dollars to labour recruiters who had promised them well-paying jobs overseas with good working conditions.

After their plight gained media coverage and human rights activists took up their cause, pressure mounted on Serbian authorities to act, Khanh says, recounting that he and others had their passports returned, their withheld salaries paid and many were repatriated home to Vietnam.

Khanh stayed on, though.

He and others continued to build the factory regardless of poor work conditions, blistering cold Serbian winters, and subsequent instances of mistreatment and strikes.

Khanh wanted to pay off the debt he owed to pay for his travel to Serbia, and as bad as the situation was, he still needed to save all the money he could earn.

“It’s like I have nothing to lose. [I am] earning some money to send home to our family. I wouldn’t regret it if I die in a foreign land,” he recounts of his decision to stay on.

Serbia did teach him valuable skills in construction, he told Al Jazeera, speaking from Phu Quoc island off the coast of Vietnam where he returned late last year.

Working in Serbia did not make him rich, and Khanh has not yet visited his hometown in Nghe An, as of this writing.

“I’m afraid of people [in my neighbourhood] looking down on me,” he explained.

“They’d say, ‘Oh, I know this guy who went overseas for work for a few years, and he bought this and that. You also went abroad, but you returned with nothing,'” he says.

“Their words are very harsh,” he added.

Between legality and illegality

Though many leave Nghe An to work around the world through formal routes – either through brokerage services or their own networks – many also talk openly about their intention to migrate and work illegally overseas.

Several told Al Jazeera about the people they knew who had already done so.

Their routes involve initially entering countries as tourists or claiming to visit relatives or, in more extreme cases, through fake marriages.

Once in the intended country, they stay on as undocumented workers.

Some are also pushed towards working illegally due to circumstances quite beyond their control, such as Nhat Tien.

Travelling to South Korea as a language student, Tien, 39, was left with little but debt when the language school he had enrolled at in Busan went bankrupt.

Though his student visa did not allow him to work full-time, Tien decided to take jobs and earn money to pay off the 300 million Vietnamese dong ($12,700) he had borrowed to go to school in South Korea in the first place. That was a very large sum in 2005.

“I was worried if I went home early, I would be a burden to my family,” he told Al Jazeera.

Finding work as a painter at a South Korean factory, Tien cleared the debt he owed before his Korean colleagues reported him to the police, and he was deported back to Vietnam.

“I had to gamble,” he said of the risks he took working illegally in South Korea.

That it paid off may explain why, nine years later, Tien tried his luck working overseas again, this time as a mechanic in Japan.

Arriving in the country legally and sponsored by a local Japanese company, Tien witnessed many Vietnamese leave the employers they were contracted to work with to find work elsewhere, and then overstay their visas.

Low salaries, a lack of overtime pay, difficult employers, as well as labour brokerage firms taking a percent of their monthly salaries, all contribute to Vietnamese workers abandoning their sponsoring companies to look for better opportunities as illegal workers in Japan, he explained.

“Brokerage companies took a commission from our salaries every month. So many workers escaped [their contracts] because they could earn more elsewhere,” he says.

There are also those who choose to work illegally overseas and in illegal businesses, such as cultivating cannabis on farms in the UK.

Cannabis farming

According to a 2019 research paper on undocumented Vietnamese migrants in Europe, cannabis farming in the UK has become a common employment sector for migrant workers.

Since about the mid-1990s, Vietnamese criminal gangs had become experts in growing cannabis in the Vancouver region of Canada.

When the UK government in 2004 redesignated cannabis as a Class B to a Class C drug in 2004 – with less severe penalties – Vietnamese gangs moved their operations from Canada and quickly became the top dogs in the UK’s cannabis business, having figured out how to turn big houses into secret cannabis farms in urban areas.

Vietnamese-led organised crime gangs have also made Vietnam a top source country for the smuggling and trafficking of people into Europe, according to an article from 2020 in the Forced Migration Review journal.

The debts incurred by people taking such journeys are used by the gangs as leverage to control migrants who are often forced to work in exploitative situations.

Nghe An native Nguyen Minh Nhat told Al Jazeera how he was weighing up – what he described as the “long-term investment” – of working on a cannabis farm in the UK.

He had talked to brokers who said they could arrange for him to get into the UK through various irregular channels. Currently working as a hired driver and holding a college degree, Nhat told Al Jazeera how he was interested in illegal work because of the potential financial returns.

“Many friends of mine from Nghe An have worked in a cannabis farm. Nobody has reported harm or danger,” says Nhat, who described the 39 Vietnamese people who died in Essex as a “rare case”.

“The brokers usually take care of getting you to the destination,” Nhat says.

“They can advise, but they don’t find you jobs. That’s up to you in the UK.”

Being arrested or robbed by other criminal gangs was a risk in cannabis cultivation, but the rewards made it worth it, he says.

Commercial labour brokers do not offer services for working illegally overseas, Nhat explained, but there are some that provide information and access as a “hidden service”.

When Al Jazeera visited an address in Nghe An’s Vinh city, which Nhat gave as belonging to the labour broker he had spoken to about cannabis farming in the UK, a reporter found a run-down residential home with no obvious business signage apart from a note taped to an entrance that read: “Put your shoes in the stipulated place”.

Taking big risks for a shot at social mobility

Nghe An and Ha Tinh provinces are the two regions in Vietnam that account for the majority of Vietnamese working illegally or living as undocumented workers in the UK, according to a 2022 study by Chung Pham, a researcher with UK-based charity Locate International.

The majority of those who died in Essex in 2019 were from the two provinces, and most – 21 of them – were from Nghe An.

According to the study, the two regions are also home to a large number of unlicensed labour brokerage companies that have traded off the success of a small number of migrants becoming wealthy from working illegally overseas.

Some of those operating unlicensed recruitment agencies and organising illegal routes to enter the UK were themselves previously victims of trafficking or had spent time in the UK’s prisons, says Luong Thanh Hai, a criminologist and research fellow at the University of Queensland in Australia, who draws from a growing body of interviews with family members of arrested brokers – including relatives of some who died in the Essex tragedy.

Hai, who also hails from Nghe An province, said brokers with direct knowledge and experience of smuggling and criminal networks were “an important link” in the recruitment chain that funnels Vietnamese people to the UK and Australia to work illegally, including on cannabis farms.

Some migrant workers who returned to Vietnam with experience of smuggling routes have initiated the smuggling of others or found themselves approached by brokers seeking to collaborate in future smuggling operations, Hai said.

They did not set out to become human traffickers or smugglers, Hai said. But after being the victims of smuggling themselves and finding themselves in debt when their plans had failed, they turned to recoup their losses any way that they could.

“They were people who invested in their journey, but it became a failure, and they were deported and returned home to a big debt,” he said.

“So they had to do something big by getting directly involved [in smuggling networks].”

It is estimated that there are between 20,000 and 70,000 undocumented Vietnamese in the UK, most of whom end up working for Vietnamese employers in nail salons, restaurants or on cannabis farms, says Seb Rumsby, a lecturer at Queen Mary University of London.

Researching undocumented Vietnamese migrants in the UK, Rumsby noticed the dominance of Nghe An residents working in nail bars during his time doing research in Coventry, a small city in central England.

“The fundamental issue is that you can work in a nail salon in the UK for well below minimum wage and still earn a lot more than you could back in Nghe An,” Rumsby told Al Jazeera.

“The government just blames smugglers and traffickers, saying it’s all the fault of these evil traffickers, and this just distracts from or ignores the actual reasons and drivers … which are largely economic,” he explains.

“This imbalance in wage difference between Vietnamese and UK salaries is not going to change anytime soon”, he adds.

Based on interviews with people in Nghe An, the flow of Vietnamese people willing to risk the dangers of being smuggled into the UK – as well as other countries – is also not going to change soon.

The shot at social mobility is worth the risk of travelling overseas either legally or illegally.

Khanh, the former migrant worker who helped build a tyre factory in Serbia, told Al Jazeera how he entered the Balkan country legally. But he also tried to enter other countries illegally.

Feeling frustrated by mistreatment in Serbia, he and some Vietnamese colleagues attempted to enter Germany as undocumented workers with the help of some brokers. Their attempt failed.

German police caught them before they could cross the border, roughed them up and sent them back to Serbia, he says.

Back in Vietnam, Khanh is again working as a construction worker during the day and taking English lessons at night because he is planning to make another attempt at working overseas. This time in Australia, where he wants to train to become a rehabilitation physiotherapist.

People from Nghe An have a reputation for being driven, he tells Al Jazeera, of working hard in school in order to get ahead in life.

But some have to work even harder in life, he says.

“In my hometown, education is low. Plus, if your parents come from a lower class in society and earn little income, then it is very hard for their children to rise up,” Khanh says.

That is why he is trying to earn a little extra money so that he can study English, learn a profession, and hopefully help future generations in his family start out a little higher on the ladder of life.

As Khanh says, he wants to “rise up, for myself, and for the next generation”.