Domestic Slave Labor in Brazil: A Delta 8.7 report

This blog post is part of our effort to support the goals of SDG Target 8.7, which saw 193 countries pledge their commitment to take effective measures to eradicate modern slavery, human trafficking, and forced and child labour. Towards that we are sharing work under Delta 8.7—part of the SDG Target 8.7 that aims to help policy actors understand and use data responsibly to inform policies that contribute to achieving Target 8.7.

In September 2021, the Brazilian Labour Inspection Secretariat reached the mark of 56,722 workers rescued from modern slavery in Brazil. The robust public policy to combat modern slavery was launched in 1995, when labour inspectors created the Special Mobile Inspection Group, which operates throughout the country. Over the past 27 years, the Mobile Group has become a global model in combating modern slavery, recognized by the International Labour Organization (ILO) as a good practice.

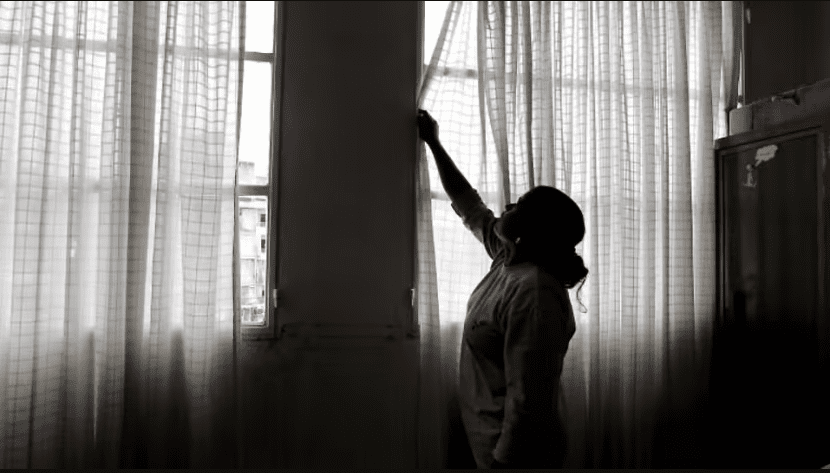

Unfortunately, new forms of exploitation that violate basic human rights continue to emerge in various sectors and, more recently, in domestic work. This latter type of exploitation, hidden in homes throughout Brazil for years, has its peculiar patterns, namely the social profile of the victims who have very similar life stories and vulnerabilities. In 2020, a case of domestic slavery gained notoriety in the Brazilian and international media, which resulted in a dramatic rise in the number of cases reported and a concomitant increase in the number of operations to remove domestic workers from exploitative situations.

Human rights violations — especially prevalent in rural areas where they have been identified and reported since the 1970s by the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) — were first discovered in urban settings starting 2002. Domestic work was one such violation that primarily takes place in urban areas. With the enactment of Constitutional Amendment 72/2013 and its subsequent regulation through Complementary Law 150/2015, domestic work gained legal visibility, and in 2017, the first rescue of a domestic worker from modern slavery took place in Brazil.

The first rescue

On 10 July 2017, a team of the Special Mobile Inspection Group initiated a labour inspection in the municipality of Rubim, in the state of Minas Gerais (MG) to verify a complaint received about the exploitation of a domestic worker. The inspectors found a 68-year-old domestic worker, who had been working without payment or time off for eight years. The worker was also unaware of her rights, thinking that her exploitative employers were doing her a favour. The Labour Inspection report notes:

The victim, (…), had known the employer’s family, (…) for almost thirty years. Initially, Mrs. (…) and her husband, when alive, worked for the employer’s father, (…). They worked and lived on the Córrego da Fartura farm in the municipality of Rubim/MG…After her husband’s death, in 2008, Mrs. (…) returned to the house (…) and went to live and work as a maid in Mrs.’s (…) house..(…) having no other residence to live in, nor an alternative livelihood, she was left to exchange her services for the shelter offered (…). Meanwhile, she was granted a pension for her husband’s death. Unaware of her rights, she was very grateful to her employer, (…), imagining that she was responsible for bestowing a benefit.

In addition to the labour exploitation, the employer also used the domestic worker’s name to take out a bank loan:

Concomitantly, the employer (…) contracted payroll-deductible loans from financial institutions, whose payment guarantee was the victim’s social security benefit (…). The victim was aware of a payroll loan, which she believed had been made by her late husband. However, after the granting of the benefit, 10 payroll-deductible loans were made, of which 3 were still active.

After the Labour Inspection was notified, the offending employer paid R$ 72,461.30 (£ 10,144.58) to the worker and an additional R$ 5,737 (£ 803.18) as individual reparation. After being rescued, the domestic worker was assisted by the Reference Centre for Social Assistance, a public institution in Rubim, Minas Gerais.

Due to the administrative origin of the infraction notice drawn up by the labour inspectors for the finding the domestic worker in that condition, the employer was added to the Register of Employers that have submitted workers to modern slavery on 10 May 2018. The employer remained for two years in this public register, more widely known as the “Dirty List”.

The Madalena Effect

Following this first rescue of a domestic worker from conditions analogous to slave labour, there has been an increase in the number of cases identified and remedied. For example, at the end of 2017, a domestic worker was rescued in Elísio Medrado, a city in the state of Bahia, after being exploited for 36 years under conditions of modern slavery. In 2018, there were two rescues, one of a domestic worker who was exploited for 29 years, and the second of an 18- year-old Venezuelan immigrant.

But the case that changed the history of combating domestic slave labour in Brazil occurred at the end of 2020, with the rescue of Madalena Gordiano in Patos de Minas in the State of Minas Gerais. The Labour Inspection found out that she had been subjected to modern slavery for over 38 years.

According to the testimony collected by the labour inspectors, Madalena reported that contact with the ex-employer began at the age of 8, when she knocked on her door to ask for food: “I went there to ask for a loaf of bread because I was hungry. She said she wouldn’t give it to me if I didn’t live with her.” Even as a child, she was banned from attending school after being “adopted”. Madalena never received a regular salary in accordance with the labour laws: “She gave me R$ 200 (£ 28) or R$ 300 (£ 42) per month,” Madalena said. This amount is one-third of the minimum wage in Brazil.

Madalena’s abusers also used her for social security fraud. They signed notary papers for Madalena’s marriage to an elderly uncle related to the family. The marriage never actually took place. The elder, who had no heirs, was a retired military man and died a year after the false marriage. The family thus appropriated the pension of R$ 8,000 (£ 1,120) a month for 17 years. Furthermore, Madalena told the inspectors that she “was given” to her first employer’s son. Her case involved the longest period of exploitation of all identified cases of modern slavery in Brazil since 2003, and it was widely covered by the Brazilian media and the international press.

Since Madalena’s case came to public awareness, the number of tips for similar cases increased, which resulted in more inspections and in more workers rescued in 2021. Even in some cases, where the employment relationship did not, in fact, constitute modern slavery, inspectors found that there were often long periods of undeclared work that was not registered. Nine months following Madalena’s rescue, the number of domestic workers rescued in 2021 was higher than in the previous four years.

Profile of Rescued Domestic Workers

Although women comprise only 6 per cent of identified people subjected to slave-like conditions in Brazil, within the domestic work sector, women constitute 80 per cent of identified victims. Regarding self-declaration of race, 72 per cent declared themselves Black, 11 per cent White, 11 per cent Asian, and 6 per cent Indigenous. This proportion is comparable to the profile of those rescued in 2020 in all economic activities, where 77 per cent were Black, 18 per cent were White, and 5 per cent were Indigenous.

Over half of the female workers rescued from domestic slave labour had completed only up to the 5th year of elementary school, with 24 per cent being illiterate, 6 per cent having completed primary education, 6 per cent incomplete primary education and 12 per cent completing high school. As for the place of birth, 25 per cent were born in Bahia, 15 per cent in Minas Gerais, 30 per cent were born in the States of Amazonas, Ceará, Goiás, Mato Grosso, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo; and 30 per cent were migrants from the Philippines, Venezuela, Bolivia and Iran.

Nine months following the rescue of Madalena Gordiano, the number of victims rescued in the country was five times higher than in 2020, and the number of inspections aimed at combating domestic slave labour rose from 4 to 30 in 2021. According to the Slave Labour Radar — the Labour Inspection’s statistics and information dashboard — 15 people were rescued from domestic slavery in Brazil in 2021 (according to inspections completed by 30 September 2021). And the number of cases continues to increase. For instance, in August, a 25-year-old woman jumped from the third floor of an apartment, where she worked as a nanny, trying to escape from her employer’s aggressions in Salvador, Bahia. In this tragic case, the Labour Inspection was still able to identify other victims of the same employer and seek restitution of their labour rights.

Challenges and gender issues

Although the identification of cases of domestic slave labour has occurred only recently — in comparison to the 25-year history of combating modern slavery in Brazil — violations have been found with the longest exploitation period ever recorded. In addition to the very similar stories of social vulnerability, factors of gender and race were also at play in cases of domestic slave labour as they are in other sectors. For example, the same patriarchal culture that makes women more vulnerable to domestic slave labour underlies the dynamic whereby, in most cases, men go out in search of support for the family, while women stay looking after the house and children — in fact, one of the primary reasons domestic slave labour is difficult to identify is because it takes place within private domestic settings. The interrelationship between race and slavery is also very pronounced in domestic slave labour, highlighting the historical debt that Brazil continues to have vis-à-vis Afro-descendants.

Labour inspections of the Mobile Group and regional projects to combat slave labour thus remain essential to combating all forms of modern slavery in Brazil. And even when they do not find slave-like conditions that lead to the rescue of workers, they often still find situations of child labour and undeclared work. Therefore, the proactive work of the Labour Inspection Secretariat serves to promote decent work and to ensure the rights of workers and children are upheld. R$ 1 = £ 0,14. Quotation on 15 November 2021.

This article has been prepared by Maurício Krepsky Fagundes as a contribution to Delta 8.7. As provided for in the Terms and Conditions of Use of Delta 8.7, the opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of UNU or its partners.