Xinjiang’s New Slavery

“Employment: Yarkant County satellite factory [for] persons in detention or reeducation.” The spreadsheet, obtained from a cache of local government files, lists the employment status of nearly 2,000 Uighurs—but the 148 entries that carry this particular designation stand out like a sore thumb.

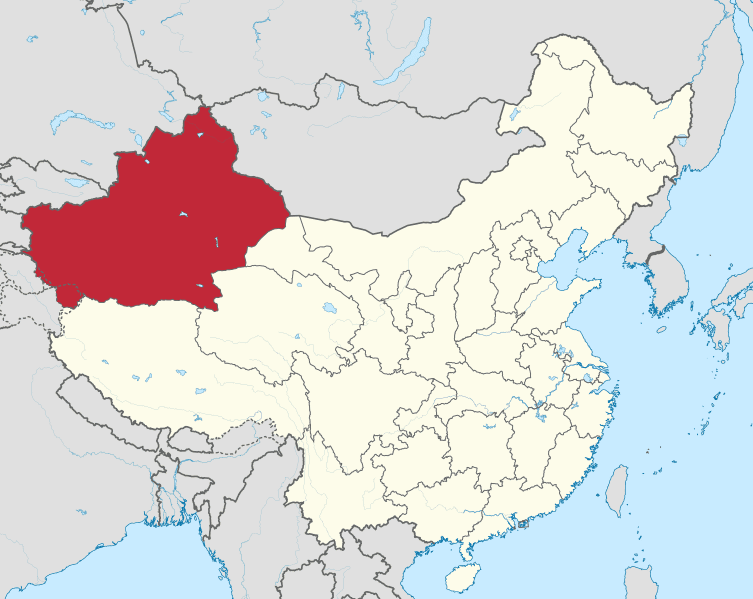

Since spring 2017, the Chinese government has placed vast numbers of Turkic minorities into internment camps, which it refers to as “reeducation camps,” in the northwestern Xinjiang region. This March, it claimed that these supposed students would gradually be released into work placements. Data such as this supports this claim, but not in the way that the government is trying to sell it. Rather, it is part of a rapidly growing set of evidence for how Beijing’s long-term strategy to subdue its northwestern minorities is predicated upon a perverse and intrusive combination of coercive labor, intergenerational separation, and complete social control.

In Xinjiang, state-mandated poverty alleviation goes along with different forms of involuntary labor placements. Under the banner of “industry-driven poverty alleviation,” minorities are being torn away from their own jobs and families. Just as brainwashing is masked as “job training,” forced labor is concealed behind the euphemistic facade of “poverty alleviation.”

The irony of placing interned Uighurs into labor-intensive sweatshops is that many of them were extremely skilled businesspeople, intellectuals, or scientists. Several years ago, flourishing Uighur businesses abroad were severely impacted by seizures of passports, and Uighurs have been progressively forced out of eastern Chinese labor markets. While there are many Uighurs living marginal economic existences, this group are not people who need unskilled labor jobs paid at around 85 cents per hour.

The first layer of the scheme is the most blatantly coercive. Under the label “vocational education and training plus,” the region is wooing mainland enterprises to train and employ internment camp detainees. Participating companies receive 1,800 RMB per camp detainee they train, and a further 5,000 RMB for each detainee they employ.

Perhaps unaware that this scheme constitutes a major violation of both Chinese and international law, Xinjiang’s regional government website openly admits that this post-internment labor scheme “has attracted a large number of coastal enterprises from the mainland to invest and build factories, which has powerfully expanded employment and promoted increased incomes.”

Read the full article here.