Burmese workers that produced F+F jeans for Tesco in Thailand report being trapped in effective forced labour, working 99-hour weeks for illegally low pay in appalling conditions, a Guardian investigation has found.

Tesco faces a landmark lawsuit in the UK from 130 former workers at VK Garment Factory (VKG), who are suing them for alleged negligence and unjust enrichment. The workers made jeans, denim jackets and other F&F clothes for adults and children for the Thai branch of Tesco’s business between 2017 and 2020.

Tesco said the garments were sold only on the Thai market, though the Guardian has seen images of labels written in English on clothes understood to be made there. Profits from sales in Thailand went back to the UK.

It is believed to be the first time a UK company has been threatened with litigation in the English courts over a foreign garment factory in its supply chain that it does not own.

The factory is in Mae Sot, a city at the Myanmar border that relies on Burmese migrant labour, and which has developed a reputation over the last decade as a “wild west” for workers’ rights. The lawsuit argues that Tesco should have known the area was notorious for exploitation.

The Guardian has investigated the allegations made by the former factory workers and interviewed 21 of them in Mae Sot. They described:

- Being paid as little as £3 a day to work from 8am to 11pm with just one day off a month.

- Detailed records kept by supervisors seen by the Guardian show the majority of workers on their lines were paid less than £4 a day and only according to how much they could make. The Thai minimum wage then was £7 for an 8-hour day.

- Having to work through the night for 24 hours at least once a month to fulfil large F&F orders, and becoming so exhausted they fell asleep at their sewing tables.

- Some reported serious injuries; one man described slicing open his arm carrying a dangerously heavy interlocker machine, requiring 13 stitches. Another said he lost the tip of his index finger after slicing it in a button machine while making F&F denim jackets.

- Many said they were shouted at and threatened by managers within the factory if they did not keep working overtime and meet targets.

- More than a dozen of the workers interviewed said the factory opened bank accounts for them and then confiscated the cards and passwords so they could make it appear they were paid minimum wage while paying much less in cash.

- Most workers relied on VKG for their immigration status and some said their immigration documents were held by the factory, leaving them in debt bondage.

- Factory accommodation within the compound consisted of overcrowded rooms with concrete floors to sleep on and dirty pond water in a bucket to wash. Workers say most rooms had no door, just a curtain.

Tesco said that protecting the rights of everyone in its supply chain was absolutely essential and that had it identified serious issues like these at the time it would have ended its relationship with VKG immediately.

Tesco started using the factory in 2017, despite its own initial inspection identifying areas of non-compliance that experts say should have been red flags.

Tesco was not involved in the day-to-day running of the factory beyond setting and checking standards and placing orders. In a groundbreaking move, however, workers in Tesco’s supply chain are seeking to hold Tesco to account for allegedly failing to protect them.

Tesco made £2.2bn profits in 2020, the last year that its Thai business used VKG.

Win Win Mya, 53, who said she was paid about £3 a day to sweep fabric offcuts from the factory floor, said: “They took that profit from us. They already have it but we don’t have anything.”

Labour experts say large clothing brands such as F&F deliberately outsource the production of clothes and the auditing of factories to avoid liability and reputational damage while keeping prices cheap and protecting profits.

The case, which is being brought by Leigh Day, challenges the outsourcing structure. Oliver Holland, the workers’ solicitor, said: “Tesco is one of the UK’s most profitable companies and our clients allege that they’re making vast profits through outsourcing the production, through workers being paid very low wages, working excessive hours, and under terrible conditions.

“It is argued that this is all solely for the profit of the companies in the UK, and so that consumers can buy very cheap clothing. Clothing that costs as little as F&F clothing is likely to be causing harm somewhere along the supply chain and that is what we have seen in this case.”

A claim has been issued in the high court and is expected to be served in the new year. Also facing legal action are Ek Chai, which had been the Thai branch of Tesco’s business, until it was sold to Charoen Pokphand Group in December 2020.

The claim has also been brought against the auditors, Intertek. Lawyers believe this is the first time that a social auditor has been brought into this kind of lawsuit.

Intertek Thailand inspected the factory regularly but did not identify serious issues until July 2020, when workers say they blew the whistle about their conditions. Workers said the factory was given notice of audits and that VKG managers coached them to lie.

The damning audit report found that nine out of 26 interviewed workers said they were not paid a day rate or the minimum wage, that they worked on Sundays and were scared to speak out.

It also said one worker reported having their ATM card taken from them and concluded that it could not verify whether the factory was compliant on hours, wages and benefits because of inconsistencies in VKG’s records.

Tesco received the audit pack in August 2020, yet VKG remained a supplier until it sold Ek-Chai in December 2020. Tesco said it immediately undertook an investigation and decided to exit the supplier but did not manage to do this before the business was sold.

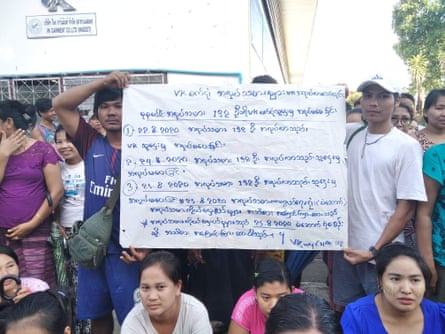

In August 2020, 136 workers at VKG were dismissed, which they said happened after they asked for better pay and conditions in the wake of the audit. They tried to get compensation from the factory directly.

In October that year, the workers filed a case with the Thai department of labour protection and welfare. They claimed they were entitled to unpaid wages made up of two years’ full wages; wages for working on traditional holidays; overtime pay; holiday pay and weekly rest day pay. But the department only ordered the payment of severance pay and notice pay.

The case then went to the Thai labour court, which reached the same conclusion. Nothing has been paid and an appeal is expected to be lodged shortly by the workers. Most are now pinning their hopes on the English case.

Thai labour experts and lawyers believe the Thai case failed in part because VKG relied on audit reports produced by Intertek that they consider to be deficient, as until 2020 it reported that VKG had complied with labour laws.

David Welsh, the country director of the Solidarity Center Thailand, said the courts tended to side with employers and that Mae Sot was “very much the wild west of the global supply chain”.

Welsh said Mae Sot was characterised by weak rule of law, poor wages and working conditions, no union access and a migrant workforce “with little to no legal protections.”

Charit Meesit, a lawyer who represented the workers in the Thai courts, has been fighting labour cases in the courts for 42 years. He said: “The authorities know what’s going on but they turn a blind eye. The courts in Thailand need to step up and do more. What I have seen for a long, long time is that employers abuse the system.”

A Tesco spokesperson said: “Protecting the rights of everyone working in our supply chain is absolutely essential to how we do business. In order to uphold our stringent human rights standards, we have a robust auditing process in place across our supply chain and the communities where we operate.

“Any risk of human rights abuses is completely unacceptable, but on the very rare occasions where they are identified, we take great care to ensure they are dealt with appropriately, and that workers have their human rights and freedoms respected.

“The allegations highlighted in this report are incredibly serious, and had we identified issues like this at the time they took place, we would have ended our relationship with this supplier immediately.

“We understand the Thai labour court has awarded compensation to those involved, and we would continue to urge the supplier to reimburse employees for any wages they’re owed.”

Sirikul Tatiyawongpaibul, the managing director of VKG, called the allegations “hearsay” and said they should be presented in court and could not be commented on, given an ongoing case in the Thai labour courts.

She said: “The company’s rules and regulations are in line with Thailand’s labour law, with employment and working conditions in line with conditions laid out by the department of labour protection and welfare and customers … the company has fought the case with facts and does not plan to shut down operations. It is necessary for the company to demand justice under Thailand’s judicial process.”

A spokesperson for Intertek said: “As a responsible business, we take the matters raised in your correspondence very seriously.

“We also note these matters are currently the subject of Thai and English legal proceedings, and therefore we are not able to comment while these proceedings are ongoing.”