Transnational Crime and the Developing World

Executive Summary

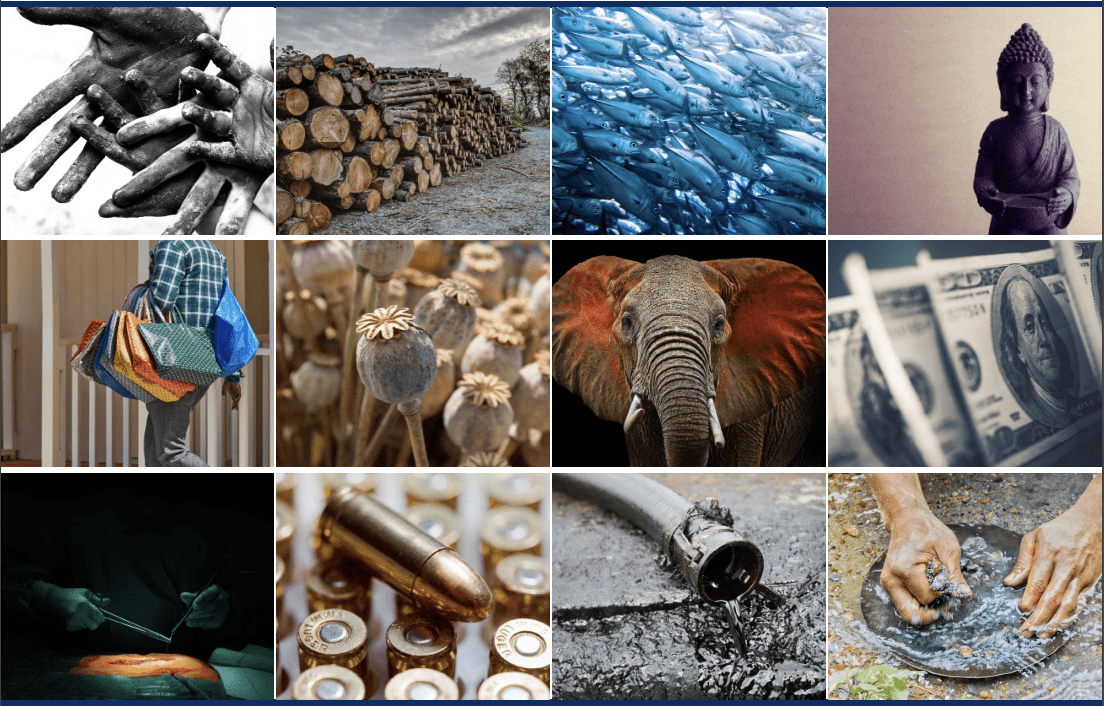

Overview

Transnational crime is a business, and business is very good. Money is the primary motivation for these illegal activities. The revenues generated from the 11 crimes covered in this report—estimated to range between US$1.6 trillion and $2.2 trillion per year—not only line the pockets of the perpetrators but also finance violence, corruption, and other abuses. These crimes undermine local and national economies, destroy the environment, and jeopardize the health and wellbeing of the public. Transnational crime will continue to grow until the paradigm of high profits and low risks is challenged. This report calls on governments, experts, the private sector, and civil society groups to seek to address the global shadow financial system by promoting greater financial transparency.

Drug Trafficking

The global drug trafficking market was worth US$426 billion to $652 billion in 2014. It represents about one-third of the total retail value of the transnational crimes studied here. Cannabis was responsible for the largest share of drug trafficking, followed in order by cocaine, opiates, and amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS). ATS and cannabis are produced all over the world, while the production of cocaine and opiates is concentrated in South America and Afghanistan, respectively. Drug trafficking organizations (DTOs), organized crime groups (OCGs), guerrilla groups, and terrorist organizations are all involved in drug trafficking. OCGs in West Africa have increased their control of the drug market in the region, and the volume of heroin trafficked from Afghanistan through East Africa is escalating, stoking consumption.

Arms Trafficking

The trafficking of small arms and light weapons (SALW) is one of the least profitable transnational crimes studied in this report, but it is also one of the most consequential for human security in developing countries. This market was worth US$1.7 billion to $3.5 billion in 2014, which represents 10 to 20 percent of the legal arms trade. Three main factors drive prices: an area’s level of conflict, political unrest, and political tension; the distance over which the items are smuggled; and, the levels of enforcement traffickers must overcome. Internet-based trafficking represents a growing challenge to combatting SALW smuggling. Decommissioned weapons that had been sold and then illegally reactivated were used in several recent terrorist attacks in Western Europe and represent another trending threat of arms trafficking.

Human Trafficking

Human trafficking, for labor and for sex, is one of the fastest-growing transnational organized crime markets. Twenty-one million men, women, and children around the world are currently thought to be victims of human trafficking, which the International Labor Organization estimates generates US$150.2 billion in profits each year. The Asia-Pacific region is responsible for US$51.8 billion of this market, with around 11.7 million victims. Developed Economies and the European Union is responsible for another third of the market value with US$46.9 billion, even though there are “only” 1.5 million victims, one-eighth as many as the Asia-Pacific region. Human trafficking is playing a growing role in terrorist and insurgent activities and groups, and the spread of the internet has provided traffickers with additional, far-reaching means to reach both victims and victimizers.

Illegal Organ Trade

Organ trafficking conservatively generates approximately US$840 million to $1.7 billion annually from around 12,000 illegal transplants. This estimate comprises the “sales” of the top five organs: kidney, liver, heart, lung, and pancreas. Kidneys are the most common for legal and illegal transplants and are the least expensive on the black market, because they can come from living donors. Brokers/scouts operate within sophisticated and specialized networks to recruit the vendors, the recipients, and the necessary medical professionals in traditional models of organ trafficking. In many cases the donor participates willingly, whereas there are further scenarios where they are pressured or forced into the transaction. Organ traffickers coerce migrants and refugees to sell kidneys to pay for passage to Europe, among others.

Cultural Property

The global annual revenue generated from the illicit trade in cultural property is estimated at approximately US$1.2 billion to $1.6 billion. This criminal market covers a range of illegal activities, including the theft of cultural property from museums, the illicit excavation and looting of archaeological sites, and the use of faked or forged documentation to enable both illegal import and export as well as illicit transfers in ownership. Estimates of ISIL’s profits from the illicit antiquities trade cover a wide range, from several million dollars to a few billion each year. China is one of the fastest growing art markets, legal and illegal, fueled in part by capital flight.

Counterfeit and Pirated Goods

The trade in counterfeit and pirated goods is the most valuable illicit trade examined in this report at US$923 billion to $1.13 trillion annually. An estimated two-thirds to three-quarters of counterfeit and pirated goods come from China. Counterfeit pharmaceuticals represent 10 to 30 percent of available drugs in developing countries. Worldwide these illicit goods are estimated to be worth between US$70 billion to $200 billion annually, which represents up to 25 percent of the total counterfeit market. Hazardous counterfeit food and useless and/or toxic counterfeit medicines endanger the health and safety of the public. For organized crime groups, counterfeiting provides an ideal avenue for laundering the profits of other transnational organized crime as well as financing other crimes.

Illegal Wildlife Trade

Estimates place the annual retail value of the illegal wildlife trade between US$5 billion and $23 billion. Ivory and rhino horn are two of the biggest components of the market value and receive the most public attention, yet the pangolin is actually the most trafficked animal in the world. Per kilo, the retail revenues for ivory or rhino horn can be equal to or greater than the equivalent amount of cocaine or heroin, yet the legal penalties are considerably more lenient. The illegal wildlife trade relies on a sophisticated global supply chain, run by well-funded organized crime groups. In developing countries wildlife trafficking robs local communities of much-needed revenue streams and has deleterious impacts on the environment, security, and rule of law, and little of the profit goes into the domestic economy.

Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing

Annual illegal and unreported marine fishing generates US$15.5 billion to $36.4 billion in illicit profits; of that, the majority is generated off the coasts of developing countries. This estimate is conservative as it does not include unregulated fishing as well as any IUU fishing in inland fishing areas. It has major environmental, societal, and security impacts in developing countries, particularly in areas where the local economy and the local diet depend on fishing. Firms that participate in IUU fishing have been linked to other crimes such as the smuggling of migrants and the trafficking of drugs and persons. The primary business model uses “flags of convenience,” whereby jurisdictions like Panama provide vessel registration for anyone in the world and typically exercise minimal oversight of the vessels, including not requiring or verifying the true, ultimate owner.

Illegal Logging

Illegal logging is estimated to be valued at US$52 billion to $157 billion dollars per year; this makes it the most profitable natural resource crime. Illegally-procured timber accounts for 10 to 30 percent of the total global trade in timber products, however this crime principally occurs in Southeast Asia, Central Africa, and South America, where an estimated 50 to 90 percent of timber from these regions is acquired illegally. Illegal logging in conflict zones often contributes to financing and fueling violence. Groups that engage in illegal logging continue to use trade misinvoicing and anonymous shell companies to evade logging restrictions and avoid scrutiny. China is the primary destination for the majority of illegally-sourced timber.

Illegal Mining

A 2016 United Nations Environment Programme and INTERPOL assessment estimates that the illegal extraction and trade in minerals is worth US$12 billion to $48 billion annually. Illegal mining is largely confined to developing countries. Experts estimate that illegal gold mining in nine Latin American countries is worth approximately US$7 billion each year. Conflict diamonds are generally thought to represent less than one percent of global production, however illicitly mined diamonds are estimated to account for 20 percent of worldwide production and were worth approximately US$2.74 billion in 2015. The exploitation of natural resources is a lucrative source of financing for organized crime groups, terrorist organizations, and insurgent groups.

Crude Oil Theft

Crude oil theft is estimated to be worth at least US$5.2 billion to US$11.9 billion annually as of 2015. However, this only includes data from six countries: Colombia, Indonesia, Mexico, Syria, Russia, and Nigeria, all of which have high levels of theft as well as available statistics. Nigeria has in recent years been the epicenter of worldwide crude oil theft. Crude oil theft in Syria currently represents the vast majority of the country’s total oil production due to the ISIL’s control of principal oil fields. The volumes of crude oil stolen in Mexico and Colombia each day are very small, but the participation of violent DTOs in oil theft in Mexico, and its use in cocaine production in Colombia, renders this a more serious issue.

Policy Recommendations

Greater financial transparency has the potential to simultaneously curtail every transnational crime in every part of the world. The networks involved in these illicit markets are akin to major global corporations, and they need access to finance and banking in order to be profitable and continue operating. Countries need to require that corporations registering and doing business within their borders declare the name(s) of the entity’s true, ultimate beneficial owner(s). Customs and central bank authorities should flag financial and trade transactions involving individuals and corporations in “secrecy jurisdictions” as high-risk and require extra documentation to try to ensure there is no illegal activity involved. Customs officers should scrutinize import and export invoices for signs of misinvoicing, which may indicate technical and/or physical smuggling. Customs agencies can use world market price databases such as GFTradeTM to estimate the risk of misinvoicing for the declared values and investigate suspicious transactions. Government agencies and departments in each country also need to share more information on the illicit markets and actors that exist within their borders. Sharing this data and this knowledge will help to avoid gaps, bolster investigations into possible abuses, and support stronger enforcement of the country’s laws. Criminals cannot afford to face this level of risk of their money or goods being detected.

Methodology

The basis of the value estimates in this report is a compilation of numerous datasets and price statistics from governments, non-governmental bodies, law enforcement, and other experts. Each illicit market chapter briefly notes the methodology and data sources used for those goods, and a detailed description of certain methodologies, as well as tables with all of the data and sources used, are provided in the Appendix. Most of the estimates the report highlights are ranges rather than a single figure, because there is less precision in data pertaining to activities that are trying to stay hidden, such as transnational crime.

Read more here.