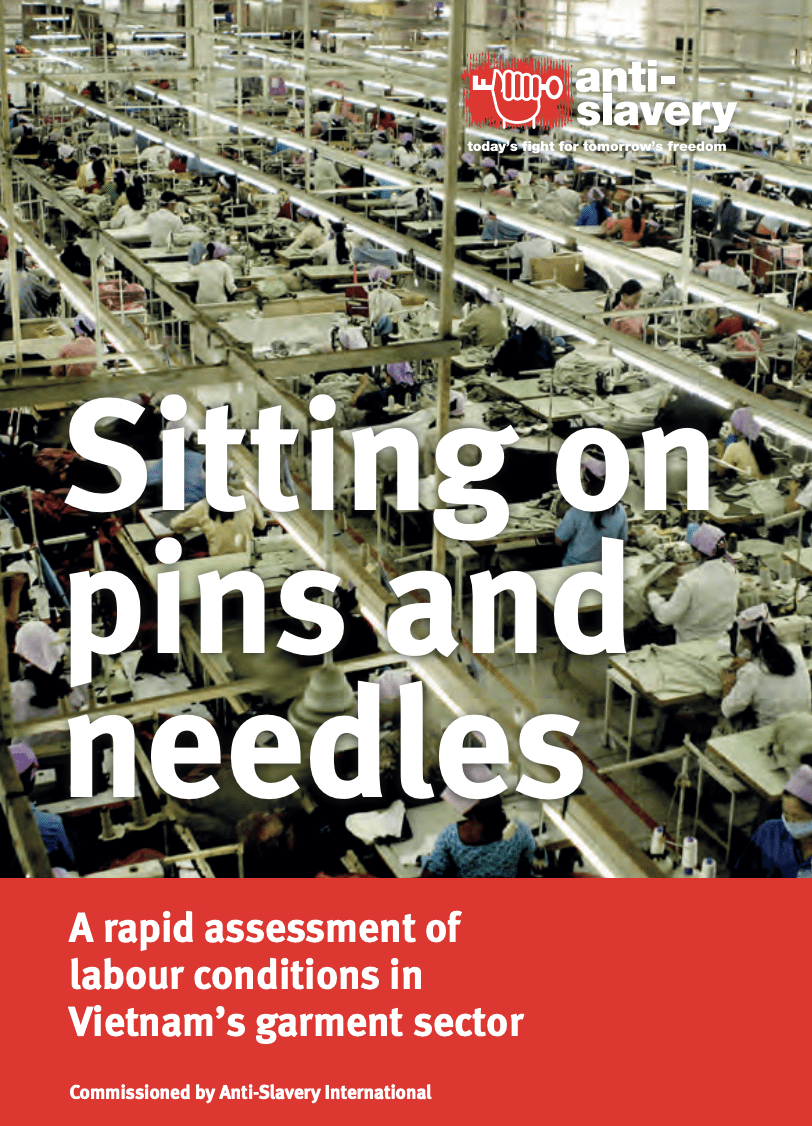

Sitting on pins and needles: Labour conditions in Vietnam’s garment sector

Vietnam is the largest garment producer in Asia after China. There are about 6,000 enterprises in the textile and garment industry in Vietnam, providing employment for an estimated 2.5 million people. Out of this, 2,500 enterprises serve the export market.1 The United States, Japan and the European Union (EU) are the biggest markets for garments from Vietnam.2 While the EU is Vietnam’s third largest trading partner, Vietnam is the EU’s 20th largest partner in the world, and the second largest in South East Asia after Singapore. The EU is not only a key trading partner for Vietnam but it is also Vietnam’s largest non-Asian investor, investing a total of US$ 1.5 billion in Vietnam in 2016. EU-Vietnam goods imports and exports grew at a doubledigit rates in 2016, quadrupling over the past 10 years to reach a total value of approximately US$ 49 billion.3 As Vietnam becomes a global giant in garment manufacturing, its records and responses to labour exploitation concerns garner increasingly more scrutiny.

This study assesses working conditions in export-oriented textile and garment industries in Vietnam, and the risk of labour rights violations, including forced labour, child labour and child slavery. To understand the context of the conditions and trends, this assessment also reviews government, corporate and other social frameworks and services for protection and standards of labour rights. Wherever possible, examples of positive business action on creating decent work conditions were assessed.

The analysis of data gathered highlights the risk of forced labour, child labour and child slavery. First and second hand accounts reveal indicators such as long hours of work, forced extension of work hours, denial of sick leave, and threat of employer retribution directed at workers who attempt to speak out.

Interviews with 21 workers across three Tier 1 factories in both the north and south of Vietnam reveal a lack of institutional protection of their rights at work. National laws are not properly enforced and as a result do little to facilitate workers’ access to their rights at work. Workers’ exposure and vulnerability to exploitation are worsened by a culture of fear, as well as intimidation and control that management assert over workers within the garment manufacturing industry. These factors prey on the workers’ lack of alternative employment should they decide to exercise or assert their rights.

Trade Unions in Vietnam are authoritarian symbols and are perceived as either extensions of management or at best serving a social function. Independent democratic trade unions are not permitted to operate in Vietnam. Workers are unclear about how trade unions really support them at work. The role of NGOs in supporting worker wellbeing in factories and supply chains is also limited, as access is restricted to specifically agreed mandates, such as training or workshops.

Workers experience a high level of stress and encounter structural vulnerabilities at the prospect of not being able to survive if they lose their jobs. Many workers are internal migrants and come from a background of subsistence farming and scarce employment. The culture of fear, intimidation and secrecy also speak to the need for greater transparency in the operations of the garment manufacturing industry in Vietnam.

Vietnam’s track record and context show that voluntary incentive-driven measures to promote business and human rights alone do not offer adequate protection to workers. Companies’ codes of conduct and auditing processes have only a limited positive impact. Identified violations in Tier 1 factories, where international brands have visibility and conduct audits, and which are usually considered low risk, show the deficiency of voluntary approaches. To reduce the risk of forced labour in garment supply chains, mandatory due diligence legislation is needed to ensure a level playing field.

The EU has a critical role to play in reducing the risk of goods tainted by labour rights violations, including child and forced labour, from entering the EU market. A systematic, pan-European approach to tackling rights violations in global supply chains is currently absent from EU policy. Moving forward, the European Commission should introduce new EU legislation that sets out clearly the human rights obligations of businesses operating in the EU.

Read more here.