The Fair Food Program works to ensure that companies like Whole Foods and McDonald’s are using agricultural suppliers with fair labor practices.

Lupe Gonzalo had been harvesting tomatoes, blueberries, sweet potatoes, and other crops for a little over a decade when, one day in 2011, workers with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers showed up at her farm. CIW, a worker-led human rights organization in Immokalee, Florida, was there to hold an education session for the farmworkers.

“They started to talk about our rights, and the changes being implemented in the field,” Gonzalo says, speaking through a translator. “And it was something that I hadn’t heard of before—the right to take a break, the right to not face things like sexual harassment while working.”

Before that session, Gonzalo says she both faced and witnessed horrible work conditions, from wage theft to sexual harassment in the fields to days without water or shade for breaks. If she or her fellow workers tried to speak up or make a complaint, she says they’d be fired or punished with the hardest work—sent to the rows of crops with the fewest or most rotten tomatoes, so it would be more difficult to harvest enough to make money. In some cases they weren’t paid for buckets they filled with crops.

“There were always repercussions,” she says. “There was no one to go to, nowhere to make a complaint. We could leave that farm we were working on but we would just go to another farm where oftentimes the abuses were either the same or could be even worse.”

Gonzalo is far from alone: Farmworkers in the U.S. frequently face labor issues. One report found that more than 70% of Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division investigations of farms have uncovered violations, including wage theft and inadequate housing. The scope of farm labor issues in Florida prompted a Justice Department official in 2003 to call the state, home to 47,000 farms, “ground zero for modern slavery.” CIW itself has an anti-slavery program that has helped free more than 1,200 farmworkers.

The day that CIW educated Gonzalo and her fellow field-workers on their rights, everything began to change on that farm, she says. The farm had joined CIW’s Fair Food Program, which meant the grower had agreed to uphold certain work conditions. From the top down, managers and crew leaders were fired if they didn’t comply with the new rules, and workers got access to clean water, bathrooms, and shade.

The Fair Food Program is a partnership between growers, farmworkers, and the food company buyers to improve conditions for farmworkers. “It was a very sudden change, and a big difference between the fields that had the Fair Food Program and the ones that didn’t,” Gonzalo says.

Since the Fair Food Program launched in 2011, major food companies including Burger King, McDonald’s, Yum Brands (which includes KFC, Pizza Hut, and Taco Bell), Whole Foods, and Trader Joe’s have signed on, as have more than 20 growers, representing more than 110 farm locations. The program launched with tomato farms, and now growers representing more than 90% of Florida tomato production are part of the Fair Food Program.

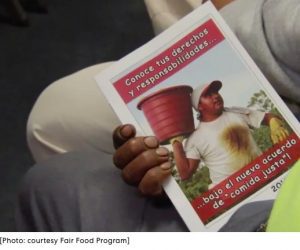

Through its 24-hour hotline for workers, the program has received more than 3,600 complaints and resolved 82% of them in less than a month. (Farmworkers can report Fair Food Program violations to the hotline; the number is on their pay slips, and education sessions also explain how to lodge complaints.) More than 72,000 workers have attended education sessions on Fair Food farms, and Fair Food audits have uncovered—and helped address—more than 9,300 labor violations.

The Fair Food Program has also received multiple awards and recognitions, most notably a U.S. Presidential Medal for CIW’s work combating human trafficking, and a MacArthur Genius Award for CIW cofounder Greg Asbed, who also helped create the Fair Foods Standards Council, the monitoring arm of the Fair Food Program. The program has expanded beyond the Florida tomato farms where it began to seven other states, and now also includes crops like lettuce and sunflowers. Last month, the Department of Labor announced a $2.5 million grant to expand the program into cut-flower farms. It could even be a model beyond agriculture; Fair Food Program representatives have consulted on projects for construction workers’ rights.

One of the significant innovations at the heart of the Fair Food Program was getting major brands like McDonald’s and Whole Foods on board. “How far does moral suasion get you with the growers? They had to put pressure on the brands themselves,” says Janice Fine, a professor at the School of Management and Labor Relations at Rutgers University.

Often, that pressure results in volunteer corporate social responsibility initiatives that are essentially pledges to do better. “But in this case, the companies at the top of the supply chains signed binding contracts with the Fair Food Program,” adds Fine, who also heads the Workplace Justice Lab at Rutgers. Those contracts require buyers to cut off relationships with growers who don’t meet Fair Food Program standards (they also pay a premium for the crops, which gets passed to farmworkers as a bonus).

This, in turn, provides an incentive to growers. “They have market pressure that’s real, so growers that want to sell their tomatoes to these major brands can’t do it if they’re found to have major exploitation at their farms,” Fine says. The program also has 10 full-time field auditors on the ground who conduct regular unannounced audits, a distinction from voluntary corporate social responsibility initiatives where audits may be few and far between. The program regularly inspects farms, including, Fine says, going up and down the rows of crops to talk to nearly every worker, and looking at their payroll records.

That has helped build trust among workers. “They were on the ground. They were there for the long haul. And workers really talked to them,” Fine says. The 24-hour hotline has also helped assuage fears of retaliation, which is one of the biggest reasons that workers don’t make labor complaints. (If a worker is on a non-Fair Food Program farm, they can still call the line, though the program doesn’t have the same powers to correct those complaints or protect workers; in those instances, the program refers the cases to the appropriate government agencies.)

“Nowhere was there more fear of retaliation and blacklisting than on farms,” Fine says. “So what they’ve made possible is for workers to feel like they won’t get fired if they come forward, won’t get punished if they come forward, and won’t get blacklisted if they come forward.”

Getting major buyers on board hasn’t been easy. The CIW has frequently held marches, boycotts, and other campaigns to apply pressure. And they’re still having to do that. Beginning March 14, Gonzalo, along with more than 100 other farmworkers and their allies, will march from Pahokee, Florida, to Palm Beach over five days, both to celebrate more than 10 years of the Fair Food Program, and to call on Wendy’s, Publix, and Kroger to join it.

Kroger and Publix (the latter is a Florida company, where CIW is based) are among the top grocery chains in the country, and CIW says Wendy’s is the only company among the top-five fast-food chains not to join—McDonald’s, Subway, Burger King, and Taco Bell are all members. While Kroger and Publix are far from the only retail food companies not in the program, they’ve rejected calls to join for years. The Department of Labor also recently identified Kroger as a retailer that purchased watermelons harvested by a company that used forced labor.

The site of that labor camp, in Pahokee, Florida, serves as the start to the 50-mile march. The investigation into that camp began in 2017 after workers called the CIW for help; in December 2022, the Labor Department announced that the farm labor contractor was sentenced to 118 months in prison. The five-day march will end in Palm Beach, where Nelson Peltz, Wendy’s board chairman, lives.

CIW has been calling on Wendy’s in particular to join the Fair Food Program for years; it launched its boycott against the fast-food company in March 2016. Wendy’s has previously said that it doesn’t participate in the program because “there is no nexus between the program and our supply chain,” that it sources its tomatoes from indoor greenhouses, and that it has its own code of conduct for suppliers.

CIW and labor experts note that greenhouse farms aren’t necessarily better than outdoor fields for labor conditions, and they also take issue with self-monitoring systems. “It’s the same reason why most companies aggressively resist unionization,” Fine says. “What they say over and over again is that they can handle this themselves, they don’t need some outsider coming in and telling them what to do. Trying to portray the union or a program like the Fair Food Program as some alien force, that’s always the first line of attack.”

But Gonzalo—who is now a senior staff member with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers and who helped plan this march—still has hope, not just that Wendy’s will eventually join the program but also that it will expand even further. “It’s the thing that keeps us going, that we hope for the most,” she says, “to be able to expand this program [and] these protections to fellow workers in the industry.”