Image: ‘Guyana, once one of the richest of the British sugar colonies, is now among the poorest countries in the northern hemisphere.’ Coffee plantation in British Guiana in the early 1800s. Photograph: Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Families like mine have listened to the descendants of enslaved people. Today we launch a new lobbying group, Heirs of Slavery

How many people in Britain today have benefited from industrialised slavery in the Caribbean? A vast and many-stranded enterprise, it was responsible for 11% of British GDP at its height in 1800. Wealth and privilege seeps down the generations, and British slavery ended only 185 years ago: there must be hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Britons whose lives are touched by the money it generated.

“You aren’t responsible for what your ancestors did. You are responsible for what you do,” says the writer on culture and racism Emma Dabiri. I examined my ancestors’ involvement in a book published two years ago. Now I, and others with similar histories, have decided we should go further.

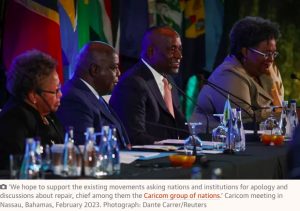

We’ve tried to listen and learn from the descendants of those who were enslaved. Today, we launch a new lobbying group – Heirs of Slavery. We hope to support the existing movements asking nations and institutions for apology and discussions about repair. First on that list is the Caricom group of nations and its 10-point action plan for reparative justice, delivered to Britain and other European nations in 2014. That request for talks has been derided and ignored in Britain (though not by the governments of Denmark and the Netherlands).

Acknowledgement, repair and reconciliation: these are good things to work for in modern Britain. We hope more heirs will join us.

They are many. Records from the 1830s show that 46,000 individuals, including two of my three-times great-grandfathers, received British governmental compensation for “giving up their slaves” at abolition, which was completed in 1838. Some put the money into land, or into shares in railways and the other tech startups of the British industrial revolution. That huge injection of cash seeded new fortunes: some of those families remain among the richest and most powerful in our country today.

You can check if your ancestors were among those compensated after abolition, sharing some £17bn in today’s money, through University College London’s Legacies of British Slavery project (LBS), and its searchable database. I know many people who have had a big shock after looking through it, their notions of their family history and of themselves turned upside down.

But LBS’s list is just of the people who held the 700,000 enslaved of the Caribbean as property at abolition – it is only a snapshot of an industry that went on for 250 years. There were a host of ways to make a fortune, or a living, out of the vast enterprise of exploiting the free labour of enslaved human beings – most without ever setting eyes on the horror that was a sugar plantation or a slave ship.

Shipbuilders, gunmakers, rum distillers, cutlery manufacturers all profited. As ever, the big money was made by the financiers – money-lenders, mortgagers and insurers – many of whose companies were gobbled up later by the banks whose names we know today.

Looking at my own family’s history, you see just how wide the economic reach of their business was. Every year they shipped out basic British manufactured goods – from salted herring and beef to cloth woven in the east of Scotland – to feed and clothe the enslaved Africans and the hired Scots men who ran their plantations.

The profits from sugar were so great that it was cheaper for the plantation owners to manufacture everything – from bricks to saddles – back in Britain and buy new enslaved people from Africa when they had worked those they had to death. The life expectancy of an African adult newly arrived in the Caribbean colonies at the height of the trade was just four years.

And at the other end of the story is government. My ancestors’ records show they paid more in tax on their slavery businesses than the family ever made from them. It is clear, too, that involvement in banks that lent money to slavers was far more lucrative than the business of running a sugar plantation. The men who helped found the Manchester Guardian for the most part made their fortunes not from slave ownership, but from manufacturing with slave-grown cotton. Obviously, that makes the people behind those institutions no less culpable.

What do you do with this knowledge? People have been getting in touch with me since I published my not-for-profit book. Like me, many are aware that though not directly wealthy from slavery, we have privilege that derives from our recent ancestors’ comfortable and empowered lives, and the violence and greed that enabled those.

“I can’t feel guilty about something I had no part in, but I do feel shame,” such people say. There’s much to feel ashamed of, then and now. But there is atonement of a sort available.

The obvious thing is to ask people who are descended from those who were enslaved what we should do. In my experience, the first answer is almost always “apologise”. Britain has apologised for its part in the Irish famine of the 1840s, for the murder of civilians in Kenya in the 1950s – why not for this great crime against humanity? Apology has power: those who mock proposals for reparation and reconciliation with west Africa and the Caribbean fear it.

And then there’s justice and money. Simply put, how can it be fair that those descended from the enslaved are so much poorer today than those descended from the enslavers? That’s generally true in unequal Britain and in the Caribbean. Guyana, once one of the richest of the British sugar colonies, is now among the poorest countries in the northern hemisphere.

Some of my family, and others I’m in touch with, give to educational projects and other organisations here and in the Caribbean. Glasgow University and the Scott Trust, owner of the Guardian, have started their own multimillion pound reparations projects. Lloyds of London and Greene King brewers have made promises. Hundreds of other institutions are watching.

We all understand this work is a token. In our case, how can you compensate for the 900 or so people who died on the plantations, and for their descendants, left to live in poverty? How to calculate the worth of a ruined life?

Charitable giving is just the easiest of many options: coalition is more interesting. Our privilege and influence can be put to use in the work that our institutions and our nation should do.

Britain’s governments and the royal family legitimised and encouraged British transatlantic slavery; it is for the whole country to address the racism, poverty and inequality that derive from it. We who are the heirs of slavery’s wealth have a part to play in that. “We cannot change the past,” says Sir Geoff Palmer, the Jamaican-born Scottish campaigner for acknowledgment of the legacies of slavery, “but we can change the consequences of the past.” That is inspiring.

- Alex Renton’s Blood Legacy: Reckoning With a Family’s Story of Slavery is published by Canongate. He is a co-founder of Heirs of Slavery