Modern Slavery: The true cost of cobalt mining

Thousands of artisanal miners dig by hand in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Children, too. They have no industrial tools, no protective clothing, no hard hats, not even facemasks to shield toxic dust or shoes. They are searching for cobalt, the rare-earth metal powering the mobile revolution.

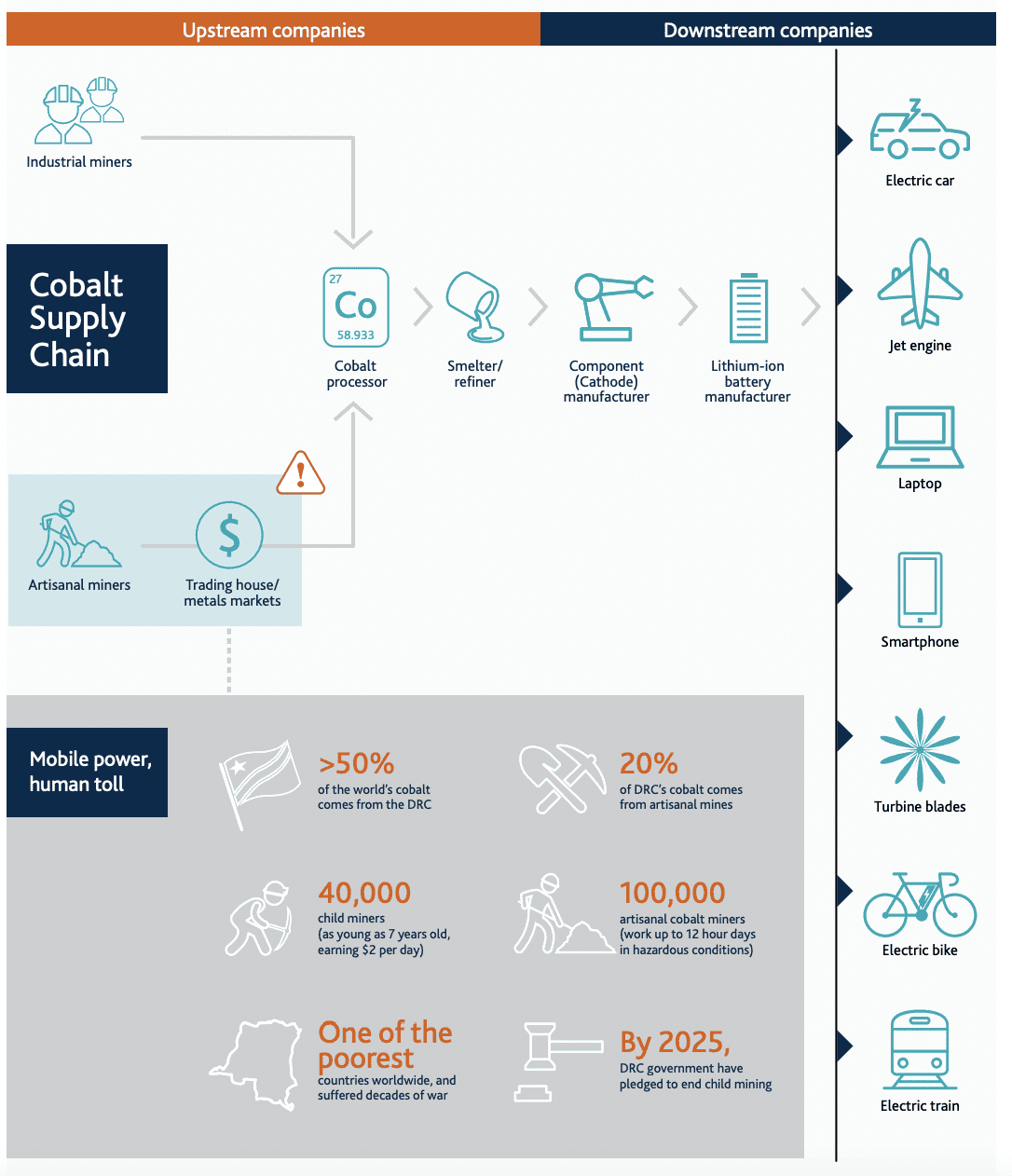

Cobalt is an essential component of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. The end product may be in your pocket, on your desk, in your garage, or even in your investment portfolio. It powers most electronic gadgets, including smartphones and laptops, and electric vehicles.

Cobalt-rich batteries are seen as a greener alternative to traditional lead-acid batteries. They are smaller, lighter and hold more energy. Favoured by tech giants, including Apple and Samsung, the innovative power packs allow consumers to reap the benefits of truly mobile technology.

The price of innovation

As innovation pushes for ever-more-slimline devices and governments look to phase out petrol and diesel cars in favour of their electric counterparts, cobalt is becoming a highly sought-after metal. In fact, some studies are predicting a 30-fold increase in demand by 2030.

This figure may seem high, but it is not unrealistic. Tesla plans to produce 500,000 electric vehicles a year by 2018, and will reportedly require 7,800 tons of cobalt to do so. The company has even built its own super-sized lithium-ion battery plant, named Gigafactory 1, to help it achieve this goal.

For investors in companies linked to cobalt mining, the most prolific of which is Glencore, this predicted surge in demand – coupled with the naturally short supply of the rare metal – means that the price of cobalt is likely to continue to rise for the foreseeable future. The flipside of cobalt’s stellar financial performance, however, is tainted by a hidden human toll.

Mobile power, human toll

More than half of the world’s cobalt is mined in the DRC, and the country’s government estimates that 20% of all cobalt production in the country comes from so-called artisanal mines that rely on human muscle (they would be better described as manual mines). In the DRC, there are at least 100,000 artisanal cobalt miners, and according to UNICEF, approximately 40,000 of those miners are children. But despite being a naturally resource-rich country, DRC is also the second poorest economy in the world. Life expectancy there is just 47 years for men, and 51 years for women. That compares to 81.2 years for the average UK citizen.

While some observers suggest that the expected surge in cobalt demand provides a much-needed source of income for people in the DRC, in reality artisanal miners are barely being paid enough to survive. Recent research by Amnesty International found that children as young as seven are working in cobalt mines, often for less than $2 a day.

To make matters worse, miners, including children, face constant risk and are ripe for exploitation. They work in wretched conditions that are extremely dangerous to their health – often with no safety equipment or protective clothing, as aforementioned. They are exposed to a near invisible poison, cobalt dust, which can cause fatal hard metal lung disease. Work hours are long, and miners labour in tunnels that are not properly supported. Rainfall can cause large areas of cobalt mines to suddenly collapse. At least 80 artisanal miners died underground in the DRC between September 2014 and December 2015 alone, and the bodies of children and adults alike are often left buried in the rubble.

A 21st century paradox

The reality of daily life for Congolese cobalt miners is clearly a long way from the lifestyles of the users of the latest tech devices. Furthermore, it seems that technological innovation is in fact fuelling the exploitation of the poor and vulnerable.

So, why are the world’s largest consumer brands willing to buy cobalt under such circumstances?

A large part of the problem is a lack of traceability along the supply chain – and the involvement of unscrupulous third parties. A significant proportion of cobalt from the DRC is sold to Chinese traders and smelters, who are often more concerned with price than with ethics.

The region’s largest cobalt purchaser is Congo Dongfang International, an ancillary of Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, which supplies cobalt to the majority of battery manufacturers around the globe. These batteries then make it ‘downstream’ into the supply chains of the consumer electronics firms, but the provenance of the cobalt used in them is often several layers removed from the corporate buyer. The use of subcontractors across the global supply chain only makes matters worse. In this way, it is difficult to determine whether cobalt from artisanal mines entered this complex supply chain.

So, even though many big brand companies claim to have a zero tolerance policy towards child labour, cobalt somehow seems to be the exception to the rule.

A lack of adequate regulation

At present, there is no regulation directly covering the global cobalt market – let alone local practices in the DRC. For example, cobalt does not fall under existing conflict minerals rules in the USA, which cover gold, tantalum, tin and tungsten mined in DRC. Activists are, however, calling for cobalt to be added to the list of conflict minerals. Without laws requiring companies to check and publicly disclose the origin of source minerals and those used by suppliers, activists believe corporates will continue to profit from human rights abuses.

Thanks to the efforts of several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) governments across the globe are starting to get the message that more needs to be done to improve the transparency of supply chains, and to stamp out all forms of modern slavery, not least child labour. For example, the 2015 UK Modern Slavery Act applies to all companies conducting any part of their business in the UK that have annual gross worldwide revenues of £36 million or more. Under this regulation, companies must now publish an annual slavery and human trafficking statement which verifies the different stages in their supply chain. Companies must also confirm that none of their corporate’s suppliers are involved in slavery. This includes identifying where and how cobalt in their products was mined.

International involvement

Interestingly, the statutory guidance of the Modern Slavery Act references the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, which “provide principles and standards for responsible business conduct in areas such as employment and industrial relations and human rights which may help organisations when seeking to respond to or prevent modern slavery.”

While the OECD Guidelines are merely recommendations, they are backed by 46 adhering governments. It has also developed a Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas, which are seen as the global standard for mineral supply chain responsibility.

Although the guidance is voluntary, the OECD has actively encouraged its adoption. For example, in May 2016, the OECD met with the Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals and Chemicals Importers and Exporters (CCCMC), a unit of China’s Ministry of Commerce, for the first time to discuss the application of the OECD’s due diligence guidance in a Chinese context.

External pressure

Ensuring ethical sourcing of cobalt from the DRC requires much more than action by policy-makers, however. Industries and investors must also make a stand if the scourge of child labour and horrendous working conditions are to be exposed and eradicated.

Amnesty International and African Resources Watch have lead the charge about human rights abuses in the DRC, particularly in cobalt, and mounted pressure on corporations to do the right thing. In a report published last year, both organisations called on multinational companies who use lithium-ion batteries in their products to “conduct human rights due diligence, investigate whether the cobalt is extracted under hazardous conditions or with child labour, and be more transparent about their suppliers.”

Read more here.