Image: Refugees at the Um Rakuba settlement in south-east Sudan. Photograph: Ed Ram

Living in UN camps in a rapidly collapsing Sudan, refugees from Ethiopia are being kidnapped, taken across the Sahara, and tortured for ransom – in a brutal, multimillion-dollar industry

Selassie’s nightmare began when men who said they were farmers picked him up, promising him agricultural work.

After managing to leave behind the violence of the civil war in his home region of Tigray, northern Ethiopia, in late 2020, he had done several such casual jobs, harvesting sorghum and digging irrigation ditches for farmers near Tunaydbah, a refugee camp in south-eastern Sudan.

This time, after Selassie and other refugees boarded the truck, they were driven deep into the desert, where the so-called farmers met accomplices armed with AK-47s. It was only then that “we realised we had been abducted”, he says.

From there, the refugees were trafficked north, to the Libyan border, and sold on to another gang. Over the next year, Selassie was held with other refugees from Somalia, Eritrea and Ethiopia, tortured almost daily and transferred between a series of cramped, airless warehouses in the desert.

The traffickers refused to release him until his family paid a ransom of $6,000 (£4,800). After that was paid, instead of releasing him, the gang simply sold him to others, who demanded a further $2,000. After that was paid, he was again passed to another group of kidnappers, who demanded the same sum.

“I didn’t think I would get out alive,” Selassie says.

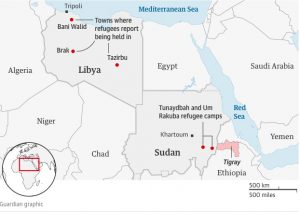

His experience is not unique. Activists and other Tigrayans caught up in the trade told the Guardian that traffickers are preying on people in Tunaydbah and Um Rakuba, two settlements that are among a series of camps run by the UN and the Sudanese government in south-eastern Sudan. Together the camps house 70,000 people who fled Tigray.

The refugees are the latest victims of the Sahara’s vast and brutal people-trafficking industry, believed to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year, stretching across Africa and trapping those fleeing wars, political persecution and economic hardship. Those who cannot pay the ransoms demanded by the gangs have no prospect of release.

Some of the Tigrayans were kidnapped by traffickers, like Selassie. Others sold on by Sudanese policemen, who had caught them travelling outside the camps without permission.

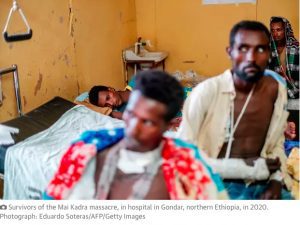

Selassie originally fled Tigray after he was caught up in violence in Mai Kadra, where he worked as a tractor driver, in November 2020. Stabbed in the chest and leg, he packed his wounds with leaves and torn-up bits of clothing.

Since his abduction from Tunaydbah, war has also erupted in Sudan as the national army and the rival Rapid Support Forces paramilitary group fight for control. Aid has dried up and refugees have started leaving the camps looking for food and shelter, exposing themselves to further predation as Sudan collapses into lawlessness.

A humanitarian worker says the safety of the Tigrayan refugees has been raised with the UN, but that no measures had been taken to help. “They didn’t really want to hear about it, to be honest. It felt like they were turning a blind eye to some clear refugee protection issues.”

Tigrayan refugees abducted before Sudan’s current conflict say they were taken to warehouses in Tazirbu, Bani Walid, Al Kufra and Brak al-Shati, towns in the Libyan desert, where they were held with thousands of others.

Traffickers demanding payment whip their victims on the feet and buttocks with cables and plastic water pipes, say several refugees. Some were burned with cigarettes. Selassie says his tormentors covered him in water and subjected him to electric shocks. When others were taken outside, he could hear their screams.

“There was no space, we were suffocated,” he says. “People were falling ill, everyone had lice. People were covered in scabs.”

While in a warehouse, he twice woke up to discover the person sleeping next to him had died. “I saw many bodies,” he says.

Two women and one man from Tigray say they were sexually abused by their captors in Sudan and Libya. One says all the women were raped in the warehouse where she was held in Al Kufra by Libyan and Eritrean traffickers.

“They took us any time they wanted,” she says. “I was raped several times. They were threatening to make us pregnant if we didn’t pay.”

The male refugee breaks down over the phone as he recounts his ordeal in a compound in Omdurman, the sister city of Khartoum, Sudan’s capital.

“One day I went to the toilet. Then a guy came and took me to another house. There was another guy in there. He pulled me in and pushed me down, and I was on the floor. They raped me. I went back to the toilet and I was contemplating suicide. I tried to tie up my belt to kill myself, but the man came in and stopped me. He locked me back where I was before with the other people.”

Inside the Libyan desert warehouses, refugees were given plain pasta and salty water. Often there was only enough food for one meal a day.

Yohannes, a 22-year-old welder from Wukro in Tigray, speaks from inside a warehouse in Brak al-Shati, where he is being held with 300 others, mostly Eritreans. He has been sick with malaria and developed sores all over his body.

“It’s a very hot place,” he says. “We’re packed so densely, I cannot turn around. On the floor there is no space to lie flat, we can only sleep on our sides. We can’t go outside because the door is locked. You don’t leave unless you pay.”