When Daniel Self, 17, a high school senior in a small town in Alabama, heard in early October about a new app that allows people to send anonymous compliments to their friends, he downloaded it immediately.

How a viral teen app became the center of a sex trafficking hoax

The Gas app lets high-schoolers send praise to one another, but an unfounded rumor has left the company facing violent threats and working overtime to save the platform. It’s not the first time this has happened.

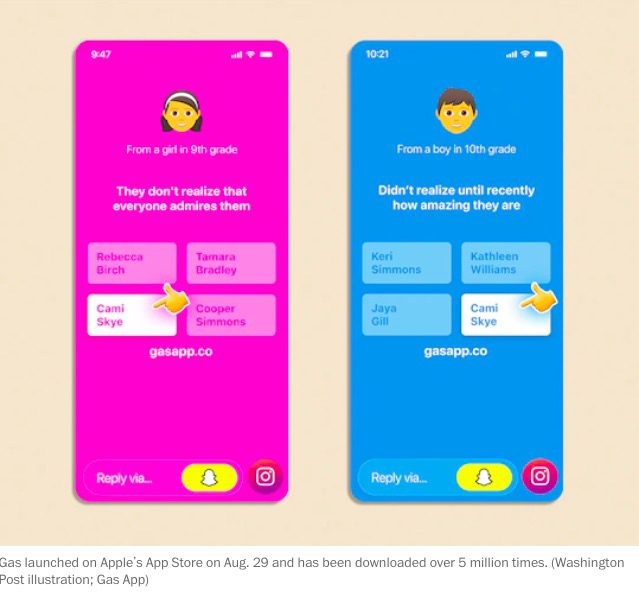

Millions of teenagers across America agreed. Since its debut in Apple’s app store in late August, Gas has been downloaded over 5.1 million times. Teenagers post about it on meme pages and their private Snapchat stories.

Self saw the rise of the app firsthand. Nearly overnight, every single person at his school seemed to have Gas. “It was crazy, it was like a light switch, it was so fast. I’d never heard of [Gas] one day, then literally everyone I knew had it and was posting about it,” he said.

Then everything changed.

A week before Halloween, Self was huddled with some classmates before school, phones out, comparing compliments on Gas, when a friend of theirs walked over. “You know, that app is for sex trafficking,” the friend told them in a nervous voice. “You shouldn’t have that, you really need to delete it.” Panicked, students at the school began deleting it en masse.

Gas has never been linked to any form of human trafficking, and the app’s very structure makes it impossible, experts say. The app has limited features, doesn’t track users’ locations and can’t be used to message someone. It’s a basic polling platform that allows users to vote anonymously on preset compliments to send to mutual connections.

But the rumor remains pervasive, plaguing the fledgling start-up and its founding team and worrying users and their parents alike.

It’s the latest example of a troubling pattern: A buzzy, consumer-facing app becomes an overnight hit, only to be beset by rumors that it’s a front for sex trafficking. It happened in May 2016 to the social app Down To Lunch; in 2018 to IRL, a social app that helps users plan in-person meetups; and in 2021 to WalkSafe, an app designed to help women gauge the safety of neighborhoods.

Despite the similar pattern, the source of the rumors remains unclear. But the narrative about Gas has been spread by police departments, local TV news and school district officials.