Hidden Chains: Rights Abuses and Forced Labor in Thailand’s Fishing Industry

Summary

Our money is with [the owner], so he can decide to give us permission [to change jobs] or not. They hold all the power and we can’t do anything. –Sinuon Sao, Cambodian migrant on a fishing vessel, Mueang Rayong, Rayong, November 2016

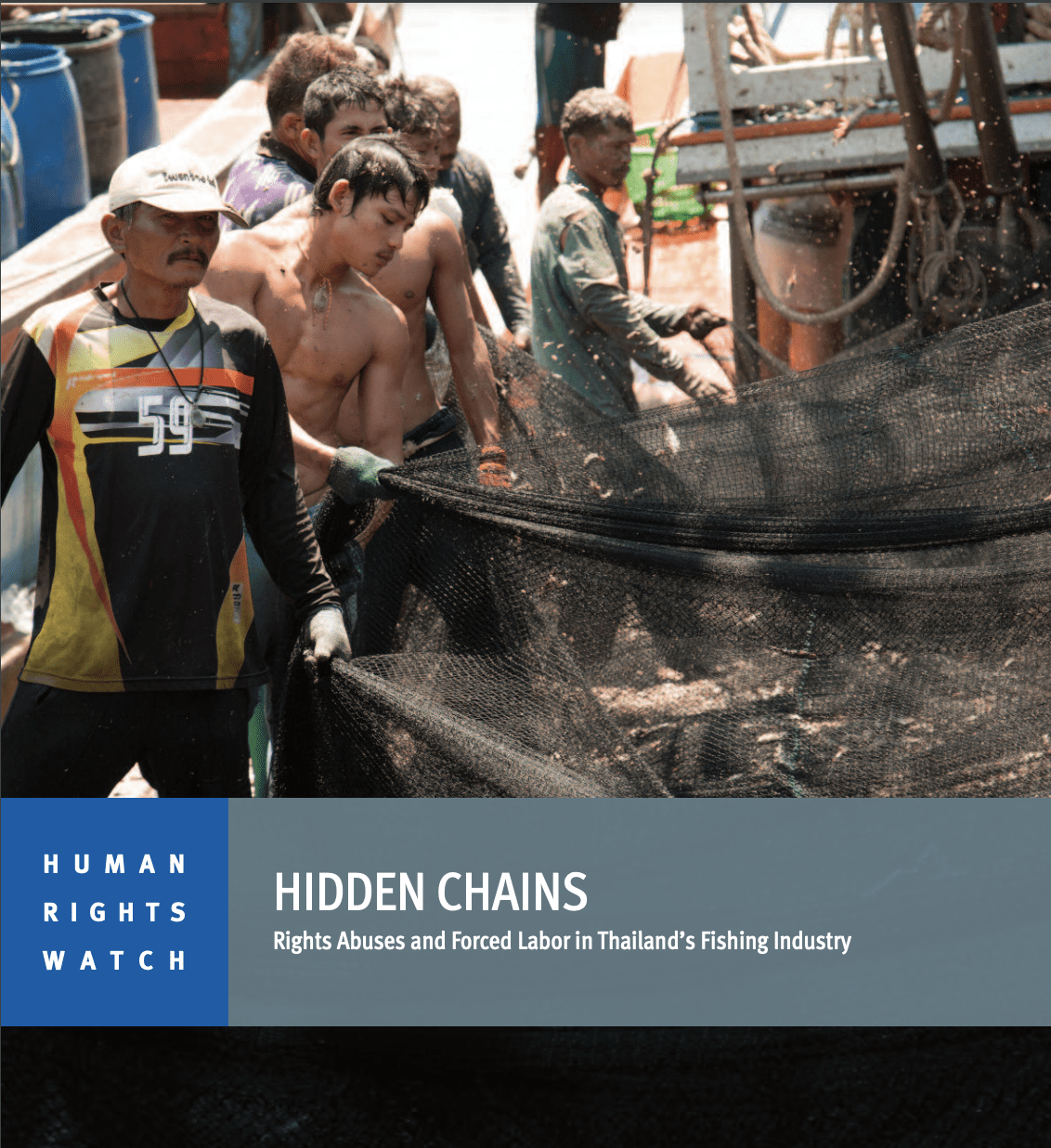

Despite several years of highly publicized efforts to address problems in the Thai fishing industry, the Thai government has not taken the steps necessary to end forced labor and other serious abuses on fishing boats.

This report documents forced labor and other human rights abuses in the Thai fishing sector. It identifies poor working conditions, recruitment processes, terms of employment, and industry practices that put already vulnerable migrant workers into abusive situations—and often keep them there. It assesses government efforts to address labor rights violations and other mistreatment of migrant fishers. It also highlights improvements and shortcomings in Thai law and the operational practice of frontline agencies that allow victims of forced labor to fall through gaps in existing prevention and protection frameworks. For example, in an official report from 2015, the Thai government noted that inspections of 474,334 fishery workers had failed, astonishingly, to identify a single case of forced labor.4

The prevalence of forced labor in the Thai fishing industry reflects a longstanding lack of respect for basic rights in the sector. Human Rights Watch’s findings show that labor and human rights violations come together under different configurations to put workers into situations of forced labor, as defined in the International Labour Organization (ILO) Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29).

In June 2014, the Guardian newspaper reported that fish caught by victims of trafficking working aboard Thai fishing boats were being used to feed shrimp grown and exported for sale in the freezers of the world’s top four retailers.5 Ten days later, the United States Department of State downgraded Thailand in its annual Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report to Tier 3, the lowest possible status. Prompted in part by numerous media exposés that raised serious concerns about killings, beatings, and trafficking of migrant fishers, many from Burma and Cambodia, the European Commission in April 2015 issued a “yellow card” warning to Thailand, identifying it as a possible non-cooperating country in fighting illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. A subsequent “red card” would lead to European Union sanctions.

In response, Thailand’s military junta, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), has overhauled fishing industry monitoring, control, and management regimes. New interagency inspection frameworks have been established across the country, and teams of officials are now supposed to check fishing boats each time they depart and arrive in port. Laws have been strengthened and penalties for infringing on fishers’ rights have substantially increased.

These reforms have focused primarily on establishing control over fishing operations and tackling IUU fishing. Yet they have had little effect on human rights abuses that workers face at the hands of ship owners, senior crew, brokers, and police officers. Meanwhile, the impact of stronger regulatory controls on improving conditions of work at sea has been limited as a result of poor implementation and enforcement.

In some respects, the situation has gotten worse. For instance, the government’s “pink card” registration scheme, introduced in 2014 in an effort to reduce the number of undocumented migrants working in Thailand, has tied fishers’ legal status to specific locations and employers whose permission they need to change jobs, creating an environment ripe for abuse. The pink card scheme, as well as practices where migrant workers are not informed about or provided copies of required employment contracts, has become means through which unscrupulous actors conceal coercion and deception behind a veneer of compliance. In this way, routine rights abuses go unchecked as officials are content to rely on paper records submitted by fishing companies and the government employs labor inspection frameworks that fail to closely examine actual labor practices at sea.

Many of the human rights problems in Thailand’s fishing industry are common to migrant workers in sectors throughout Thailand’s economy, whose exploitation is aggravated, and sometimes caused, by the government’s haphazard national policies on labor migration.

In its migration policies, the Thai government has sought to balance negative public attitudes about migration and alleged national security concerns about migrants with strong economic demand for low-cost labor. The result has been contradictory and inconsistent migration policymaking. Its current orientation toward stronger controls and crackdowns on irregular migration have proven ineffective and merely pushed migrants toward more expensive and less safe border crossings, increasing profits for smugglers and traffickers.

Read more here.