Chatri stared out the window at the unfamiliar landscape, trapped in a country that wasn’t his. He was with some two dozen people like himself—mostly Thai nationals, in their teens and early 20s.

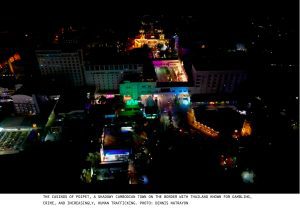

The 16-year-old was attempting to figure out where they were when he noticed a gleam of lights ahead. He didn’t know it at the time, but they were the casinos of Poipet—a shadowy Cambodian town on the border with Thailand known for gambling, crime, and increasingly, human trafficking.

“I didn’t know how I would survive this. It was like going to hell all over again,” Chatri, a pseudonym given for his safety, told VICE World News in an interview in Thailand after his rescue from Cambodia.

The bus had been driving for nine hours from the Cambodian coastal city of Sihanoukville. Following behind were anti-trafficking volunteers, tailing the vehicle through the night. They were in communication with another victim inside who had kept a phone hidden from his captors. When the bus pulled over at a gas station, the young man messaged an investigator leading the operation.

“I think we’re coming to a stop,” he wrote. “Are you coming now?”

The operation late last year—led by the Immanuel Foundation, a newly-formed anti-trafficking group consisting of former police investigators, retired military, and other volunteers—had been in the works for weeks. It represents just one of a growing number of rescue efforts responding to a human trafficking crisis that has taken root in Southeast Asia since 2020, as low-wage workers have been lured from across the region into industrial-scale scam mills. There, they’re abused and forced to steal from strangers worldwide using sophisticated online scams, in an industry responsible for the theft of potentially billions of dollars each year.

Sandwiched between Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos—three countries playing host to major scam operations—Thailand is increasingly serving as a major source of, and transit point for, trafficking victims to those countries. That’s where the Immanuel Foundation steps in, conducting rescues at the request of victims and their families.

A Thai man in his 40s, Tawanchai is the Immanuel Foundation’s director, and led five volunteers conducting that rescue. He requested a pseudonym to protect himself from the criminal syndicates he targets through his work as he recalled how events unfolded in an interview with VICE World News in Bangkok.

“All night my team was awake, following closely behind them,” he said. “I called the victim with the hidden phone and explained that we’re not far behind.”

Once the bus came to a stop, the volunteers burst from their vehicles, Tawanchai said. This time they were lucky—there were no armed guards accompanying the trafficking victims, a rare occurrence but something that he said they must be prepared for.

While they waited for the land border crossing to open up, the rescuers and victims hunkered down together in a small hotel. When one of the young trafficking victims went downstairs to browse for snacks at a corner store, an unidentified man, likely with the Chinese cartel, tried to force him into his tuk tuk. Tawanchai’s volunteers saw what was happening and intervened, pulling the victim away before he disappeared into Poipet’s crowded streets.

“For us, it’s very dangerous,” he said. “We know who we’re dealing with. But often with these interceptions, the victims are delivered in public vans, or the driver has been told very little, or in many cases they just give up the victims when we confront them. We know they don’t want any problems.”

A significant number of victims are Chinese nationals, while Malaysian, Taiwanese, Indonesian, Philippine, Vietnamese, and Thai nationals have all been reported among trafficking victims. A VICE World News investigation in July pieced together various estimates from officials and victims, placing the number of victims in Cambodia alone at more than 10,000. Thai law enforcement sources and Immanuel Foundation told VICE World News that the number could be close to 100,000 considering the range of locations across Southeast Asia.

Jacob Sims, Cambodia director for International Justice Mission, an NGO that works with victims of human trafficking and forced labor, told VICE World News in July, “What’s going on inside these scamming compounds feels like a true humanitarian crisis.”

It’s unclear who is behind the operations, but experts say many criminal groups are tapping into this new illicit market. What is known, however, is that they are often run by Chinese nationals, working closely with corrupt local officials. Experts believe that the casinos in Cambodia and elsewhere in the region, already known for laundering money with links to organized crime, are involved.

In response to international pressure, Cambodian authorities have made attempts to clamp down on the syndicates, occasionally raiding compounds and freeing victims. But despite crackdowns on compounds throughout the country, sources on the front line of a cross-border effort to rescue victims say the crisis isn’t going away.

Based on over a dozen interviews with recent victims of trafficking, and interviews with law enforcement and others responding to the crisis, the criminal cartels appear undeterred. According to the Immanuel Foundation and Thai authorities, the criminal syndicates are relocating to Myanmar, the Philippines, and even as far afield as Dubai.

“It’s worse than before. The amount of slave labor is just as high, if not higher, and now we understand the extent of the problem,” Tawanchai said. “The Chinese groups are just changing locations, and the cases are increasing.”

In Poipet’s city center, the destination of the bus intercepted by Tawanchai, hawkers sell fake cigarettes and counterfeit bottles of Johnny Walker. Metal shacks stand in contrast to the billion-dollar casinos that pepper the area. Children and the disabled beg for loose change as Chinese and Southeast Asian tourists stumble across the land border. At night street children comb the streets looking for scrap metal to sell for pennies.

From above, the complex resembles a small international airport. Situated less than 10 kilometers from Poipet’s main border crossing with Thailand, the enormous scam compound sits awkwardly against a backdrop of small shops and low-income housing.

Approaching the compound, a former local security guard for one of the syndicates, accompanying VICE World News on a ride along, explained the bleak situation he saw inside the scam center’s walls during his eight months working there.

“Inside there are hundreds of workers who cannot leave. I’ve seen this with my own eyes,” he said on condition of anonymity. “The workers inside are beaten or electrocuted if they misbehave. I’ve seen people try to escape, but no one was successful.”

The former security guard comes from an extremely low income background, working odd jobs for years. But he said he could no longer continue to work at the compound after he had witnessed what was happening there.

Minutes earlier, VICE World News passed by a separate block near the hustle of Poipet’s city center, which according to the guard, contains two smaller occupied compounds. As the car circled the buildings, blue metallic fencing encased concrete walls, and barbed wire crept everywhere.

At the entrance, a group of security guards stood in military fatigues. When the car approached, one of the guards spotted the team. He made hostile expressions as he eyed-down the SUV. The guard said it still holds an unknown number of victims.

Since the pandemic hit, Tawanchai’s team has been rescuing victims trafficked across the region. On the outskirts of the Thai capital Bangkok, he takes VICE World News to meet a pair of recently rescued trafficking victims.

Tawanchai comes from humble beginnings. Born to an ethnic minority group in Thailand, his family lived in the countryside as Christian missionaries. He was in middle school when he first encountered modern slavery. One of his friends, a young girl, was taken away from her parents and forced to be a sex worker. In Thailand, this form of “recruitment” is relatively common: strange men approach desperate parents in rural parts of the country offering money to take their daughters to work in large cities, often working in bars or massage parlors.

That’s when he knew one day he would work against this harmful form of exploitation. A decade later, he joined an anti-trafficking department with the Thai police. Later he went to work for an international anti-trafficking organization combating sex-trafficking. He says the job is a calling, and accepts it comes with risks.

Four years ago, a criminal syndicate tried to track him down for his work. He was followed and threatened, and pushed into hiding. Eventually the criminal group, who were involved in sex-trafficking underage girls, were jailed.

But rescuing victims in the current scam-mill context is not as straightforward as it may seem. Thai authorities say that in some cases, people working in the compounds are there by choice, making upwards of $2,000 a month to conduct the sophisticated scams, muddying the waters on who are criminals and who are victims. Today, when victims of trafficking are brought back across to Thailand or elsewhere in the region, law enforcement sometimes charge them for violating local cyber crime laws despite pleading with police that they’ve been deceived by gangs.

The Immanuel Foundation team is urging the Thai government to adopt new police screening methods that would distinguish genuine cyber criminals from victims of human trafficking. For Tawanchai, it’s all about proving to authorities that the people he helps are victims—not criminals.

“I witnessed at least four people being physically assaulted. They also pushed me down to the floor and started hitting me,” she said. “One of them shocked me with a taser, and started kicking me and my friends on the floor.”

At one point, she recalled the entire office had to move buildings to avoid a police raid. When they relocated, the criminals became increasingly agitated.

“They cuffed all of us together,” she said. “On the fourth day after we got moved, because of the raid, that’s when they started starving us. We had to drink water from the faucet to stay alive. The abuser was there constantly and the translator, he was always there. He held the taser in his hand the whole time. Never let it go.”

After two months, her worst moment arose shortly after her family came up with ransom money for her release. Before they let her go, the criminals forced her to fully undress in front of them. The men pulled out their phones and started taking photographs of her naked body to use as blackmail.

“If you go to the police we will share these images of you online,” Som recalled the Chinese office manager telling her. “Remember, we have people who are much more vicious in Thailand. If you tell the police what happened here, then they’ll come handle you.”

The Manila-based compound is reportedly still operating with approximately 1,000-1,500 forced laborers, 300 of which are Thai, in the compound at the time of writing, according to Immanuel Foundation estimates.

Som’s experience mirrors countless others who have faced similar horrors.

Saranya, also a pseudonym used for her protection, told VICE World News that she was trafficked to the Cambodia-Vietnam border of Krong Bavet in late December.

“They confiscate everyone’s identification—passports, ID cards, everything,” she said. “There was a young boy who came with us at the same time, they attacked him, and choked him.” Another group of victims trafficked to Sihanoukville told VICE World News that if they fought back, they would be beaten or even killed. Saranya’s compound in Bavet currently holds close to 1,000 victims, according to Immanuel Foundation estimates.

“One day we heard someone died,” one victim who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity told VICE World News. “We looked outside from our window and we saw a body lying on the ground who had fallen from a high floor above. They threw him off the balcony.”

Inside Poipet’s Crown casino, all you hear is the roar of digital spinning reels, loud beeps and chimes. Rows of slot machines, digital roulette tops, and blackjack tables fill the space. Cigarette smoke drafts through the area as gamblers openly light up between sips of cheap cocktails. The bright lights are unbearable–designed to keep you disoriented, awake all night.

“The online rooms are just down those escalators. That’s where they take people to work all night, all day,” said Annop, a pseudonym to protect him from legal reprisals. Annop co-owns and manages one of Poipet’s small scale online casino operations, competing with the brick and mortar casinos like Crown near his office. He’s a Thai national in his mid twenties, overweight, sports a small handlebar mustache and tattoos trace up most of his arms.

“There’s so much money in this online work. We’re not the only ones opening these businesses.”

Online casinos have been outlawed in Cambodia since 2019 but many career criminals like Annop are not afraid of law enforcement. He says local police are paid off to look the other way. However, in cities like Phnom Penh and Bangkok, police are cracking down on the illicit businesses as they’re known to commit fraud and exploit their laborers, according to law enforcement and other experts.

Later that night Annop and his crew visited one of Poipet’s KTVs, a nightclub where clients can rent a private room with a karaoke system. In places like Poipet, people don’t use them for singing: instead the privacy of the soundproofed rooms allows for prostitution, drug use, and other debauchery. Inside, electronic music blared over the unsettling flash of countless green LED lights. Women snorted long lines of a mixture of ketamine and ecstasy, drank happy water, and danced to pulsating music.

Annop pulled out his phone and started showing VICE World News images from inside his cyber casino. Rows of computers are seen filling a large room. It looks like a small operation, but then he said the business makes millions of dollars a month with 12 people working in shifts, 24 hours a day.

Before setting up his operation, Annop sold methamphetamine in northern Bangkok. But when he heard how much money he could make from “working online” as he often casually refers to the shady business, the option to change careers became clear.

When pressed for more details on how he opened the cyber casino, Annop became cagey with the details. He admits that a Thai business tycoon owns the majority of the operation, while he owns a fraction of shares. He said the man is a powerful figure in Thai politics, but refused to name him.

He claimed that they don’t hold workers against their will, while acknowledging that other groups like his do.

“I know they traffic people,” Annop says of the brick and mortar casinos in the town. “I know they hurt a lot of people too.”

But Annop’s group of criminals are not a harmless bunch. They admit to using violence to protect them from “our enemies,” and openly carry 45. caliber revolvers casually tucked into their waist bands. Ananda’s close associate claims to be a former assassin.

“Sometimes we have to make difficult choices,” he said. “We know what we’re doing isn’t legal, it’s a gray business, but we must make a living.”

It later became apparent that Annop wasn’t telling the full story. Although VICE World News could not verify if his business was entangled in human trafficking, a former employee said they were involved in fraud and exploitation.

VICE World News spoke to a former employee of the cyber casino, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. He said that he went into hiding after he left for “making mistakes,” describing the reality of working under the group.

“It’s a free city; gambling, drugs, guns. That’s why people come here,” he said.

“Online casinos like ours are illegal because they scam customers,” he told VICE World News. “When customers make a deposit, they’d shut down their website.”

When asked further about how they scam customers, he said: “Are they rigged? As in arranging for customers to lose? Some [of our]websites are like that. They call it ‘bet fix.’ It’s a system that makes customers lose.”

He explained the managers don’t explicitly hold workers against their will, but if the employees didn’t hit their targets things could get ugly. He said Annop’s team and the mysterious boss were capable of using violence and intimidation to keep employees in line. Although the employees received pay, he says the wages were extremely low in comparison to the profits the business was making.

All of the workers were kept under tight surveillance and would be punished if they “sold information” or “made mistakes,” he said. On top of this, he made it clear that competing cyber casino groups were capable of being violent. When VICE World News asked what that violence looked like—he was blunt.

“Abductions, kidnappings, and killings,” he said, referring to the risks of rival cyber gangs.

Victims keep surfacing all across the region. Tawanchai admits he’s struggling to keep up with the magnitude of the problem. One week, he’ll help bring a group of Thais across the border, but then others are duped into working for the syndicates days later. He spent the last few weeks trying to bring home a 14-year-old girl who had been languishing in a Cambodian immigration detention center after she was released from a scam compound. After traveling to Phnom Penh, he successfully negotiated her release a few weeks ago.

“We finally got her out,” he said. “But there are still so many more,” he added, before estimating some 3,000 Thais are still stuck in immigration detention centers in Cambodia.

It’s a complex problem also acknowledged by Thai law enforcement. In exclusive interviews with VICE World News, agents from Thailand’s Department of Special Investigation, often referred to as Thailand’s equivalent of the FBI, said the scale of the problem is overwhelming. Despite significant efforts, the problem demands increased cross-government coordination and assistance from Cambodian authorities: assistance investigators allude isn’t always provided.

“It’s getting better, a little bit, as we are able to rescue people and governments are noticing this problem,” Police Major Siriwish Chantechasitkul, the director of the DSI’s Human Trafficking Bureau, told VICE World News. “But this problem is not going away.”

Siriwish said the Chinese groups were shifting to Myanmar. But he also noted that there were new cases of trafficking coming out of the Philippines and Dubai, signaling that the Chinese cartels have set up shop in locations beyond the Mekong region. Other than online fraud, his team has received reports about Thai women being brought to the United Arab Emirates for sex trafficking. He said this could be connected to organized crime in Thailand.

“We’re seeing that most of the bosses in Dubai are Chinese nationals,” he said.

He added that the operations in Dubai lured in mostly Thai women, offering domestic working jobs or employment at massage parlors. But once they landed in Dubai, they were met by Chinese gangs, then quickly forced to perform sexual services.

“If they don’t work, we are hearing reports of physical abuse as well,” Siriwish added. “And it’s the same there too, in order to leave the country, they also have to pay a ransom.”

A Thai private investigator, who goes by the nickname Bird, has been helping rescue trafficking victims of scam centers since 2020. He said he had also heard reports of Thai women trafficked to Dubai for sex work and believes it could be the same gangs running online scams in the Mekong region. He’s aware of at least ten cases of Thai women being trafficked to Dubai for sex work since December.

That evidence, for now, remains anecdotal; the women who have returned told him that the “bosses” were all Chinese, and he said the sex traffickers used the same types of advertisements on social media as the online scams.

Tawanchai, the Immanuel Foundation director, shares the concern that trafficking is expanding despite the heightened scrutiny from authorities. His primary fear is that the criminal groups, whoever is behind them, are getting smarter and more sophisticated.

“They’re better at evading detection now, better at evading arrest. And they don’t feel threatened because there have been very few charges, no legal response,” he said. “So they have this idea that they can just get away with it.”

“If we don’t stop them soon, then they will just keep getting worse. There will be more and more victims.”