From moral responsibility to legal liability?

Modern day slavery conditions in the global garment supply chain and the need to strengthen regulatory frameworks: The case of Inditex-Zara in Brazil

Executive summary

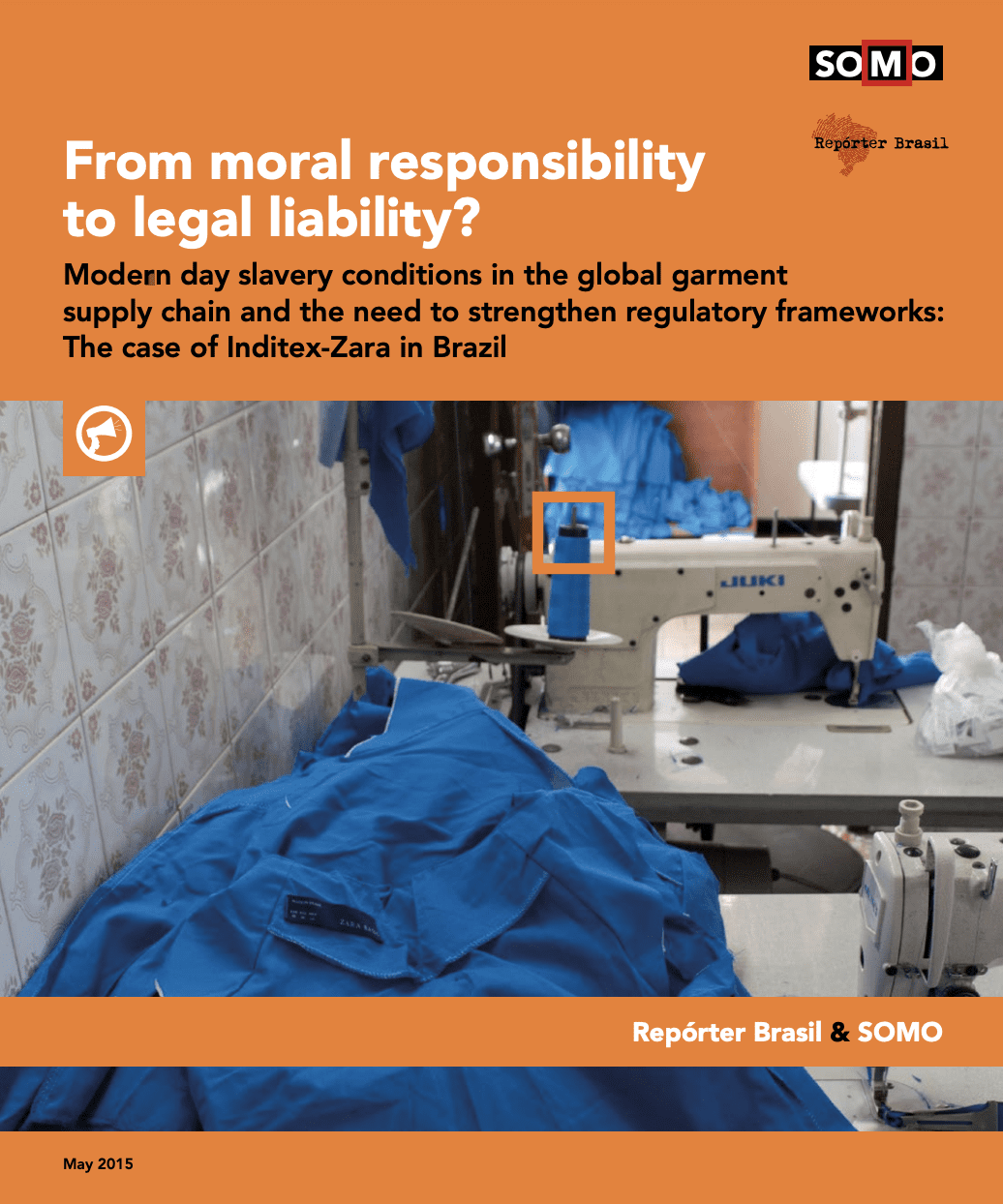

In August 2011, Brazilian federal government inspectors found 15 immigrants working and living under deplorable conditions in two small workshops in São Paolo. Workers had to work for long days – up to 16 hours – and were restricted in their freedom of movement. The inspectors later concluded that the conditions in the two workshops were to be classified as ‘analogous to slavery’. The workers were sewing clothes for Zara, a brand of Inditex, the world-renowned fast fashion pioneer from Spain. The workshops where the abuses took place were contracted by Zara’s supplier.

According to the inspection report, Zara Brasil exercised directive power over the supply chain and therefore should be seen as the real employer and should be held legally responsible for the situation of the rescued workers.

The company faced several sanctions: it was fined for 48 different infractions found during the inspection of the workshops; and the company risked entering the so-called ‘dirty list’ of slave labour – a public registry of individuals or enterprises caught employing workers under conditions analogous to slavery. Zara Brasil has been fighting these sanctions in court, which challenged the legitimacy of the dirty list as a tool. The current report questions this litigation strategy.

Objectives

Based on an analysis of the case of forced labour in Inditex’s supply chain, this report will demonstrate that voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives and self-regulation are insufficient as a tool to address human rights violations in the global garment industry. Additional legislation is required.

Several initiatives undertaken by the Brazilian government to counter forced and slave labour have been described as best practices. In order to adequately address serious labour rights concerns in the Brazilian garment industry, however, the Brazilian regulatory framework needs further strengthening. By publishing the current report, SOMO and Repórter Brasil aim to help further strengthen these measures, as well as making the case for introducing supply chain liability in the Brazilian regulatory framework.

Inditex’s actions following the case of modern day slavery conditions:

Improving CSR policy and practices

The slave labour scandal in workshops producing for Zara Brasil has led to a number of improvements in the company’s operations, such as a significant increase in the number of inspections, strengthening of its supplier monitoring mechanisms and investments in immigrant communities’ projects (for further information see chapter 6).

Persisting weakness in monitoring system

One of the major issues in the Brazilian garment industry is the high incidence of outsourcing and subcontracting through which informal workshops are incorporated in the supply chain. In these informal workshops, the risk of serious human rights and labour rights violations is high. SOMO and Repórter Brasil are of the opinion that Inditex’s monitoring mechanisms, although strengthened, are still not adequately addressing this problem. In July 2013, during a hearing at the Labour Prosecutor’s Office, Zara Brasil itself could not guarantee that informal workshops were no longer part of its supply chain.

The current research provides indications that the company’s supply chain monitoring is not 100% effective. The examples of companies included on Zara Brasil’s supplier list, even though they had been out of business for months, illustrate this (see cases of ND Confecções and Rolepam Lavanderia Industrial in Chapter 6).

In addition, labour rights infringements at a number of other suppliers and subcontractors (see annex I) were not reported to the Labour Prosecutor’s Office (MPT). Based on an agreement between Zara Brasil and the MPT, corrective action plans must be adopted and sent to the authorities if the company’s audits reveal inconsistencies with the Brazilian labour law and the Inditex code of conduct. Inditex is of the opinion that the labour rights infringements fall outside of the scope of the agreement. SOMO and Repórter Brasil are of the opinion that Inditex is not fulfilling all of its obligations as laid down in the agreement with the MPT, a view that is supported by the Parliamentary Inquiry Commission (CPI) that was created by the Legislative Assembly of São Paulo to investigate cases of slave labour in the state. And even though Inditex states that it was aware of and played an active role in resolving these issues, SOMO and Repórter Brasil have received no supporting evidence for this.

Harmful litigation strategy

In June 2012, Zara Brasil filed a lawsuit against the Brazilian authorities, contesting both the fines that were imposed on the company as well the decision to put Zara Brasil on the so-called ‘dirty list’. By means of this court case, Zara Brasil has not only been contesting its own legal responsibility, but also the constitutionality of the dirty list as a tool to fight slave labour. The argumentation used by the company is that the Ministry of Labour should not create penalties (eg: blacklisting), but should only apply those penalties already provided for in existing laws or collective bargains.

The company’s litigation efforts against the labour inspection and the ‘dirty list’ risk undermining the potential of the Brazilian authorities to effectively fight other situations of modern slavery in the country, not only in the garment industry but also in many other economic sectors1 . The list’s extinction would remove the main search reference for Brazilian companies committed to eliminating the use of slave labour in their business relationships. SOMO and Repórter Brasil argue that the company’s alleged commitment to human rights is incompatible with its explicit attempt to undermine a tool that is an international example of good practice in fighting forced labour.

Moral responsibility versus legal liability

In its response to the 2011 slave labour scandal, Inditex combined progressive measures in the voluntary CSR realm with reactive litigation in the legal realm. In other words: it voluntarily assumes ‘moral’ responsibility but resists legal responsibility for the working conditions within its supply chain. In fact, this combination of strategies reveals an inconsistency: in the CSR realm, Inditex assures its stakeholders that it is able to effectively monitor its supply chain, while in the legal realm, it refuses to assume responsibility for the conditions in the sewing workshops, arguing that outsourcing was unauthorised, Zara Brasil was not aware of it and that its contracting party had been deceiving audits, i.e. Zara Brasil is unable to control its supply chain.

There is another inconsistency in Inditex’s approach: while it has publicly acknowledged the value of the dirty list as a tool to combat slave labour by joining the National Pact for the Eradication of Slave Labour, the company’s legal strategy undermines the tool, as it jeopardizes the very existence of the list. Repórter Brasil and SOMO are of the opinion that the dirty list and other measures to combat slave labour in Brazil need strengthening instead of weakening.

Legal liability of brand owners: a step that needs to be taken

The present report demonstrates once again that private audit systems and certifications are not sufficient to overcome labour precarisation and human rights abuses in the textile and garment industry. There are many more examples of severe human rights abuses occurring in the supply chains of Western brands and retailers.2

Slavery, deadly fires and other kinds of rights violations faced by workers largely reflect a business model that focuses on low-cost production. A model in which big brands and retailers have broad discretion to influence the working conditions imposed on their manufacturer networks. In this scenario, the understanding that retailers have a mere “social responsibility” for workers’ rights must be urgently left behind.

Voluntary supply chain monitoring is neither a sufficient nor a fair solution to the problem of slave labour and other recurrent labour rights violations. It does not erase the economic impetus that is driving precarious and illegal workshops to be a significant part of the garment industry. In fact, it leaves the legal responsibility for labour and human basic standards with the workshop owners, while the powerful economic actors in the production network – brand owners and giant retailers – benefit from low-cost production while ’outsourcing’ the risks of legal sanctions for human and labour rights abuses.

Read more here.