Faced With Questions About Forced Labor in China, the I.O.C. Is Tight-Lipped

Olympic officials are reluctant to probe whether any Beijing 2022 merchandise might have been made under duress by Uyghurs, an activist group charges.

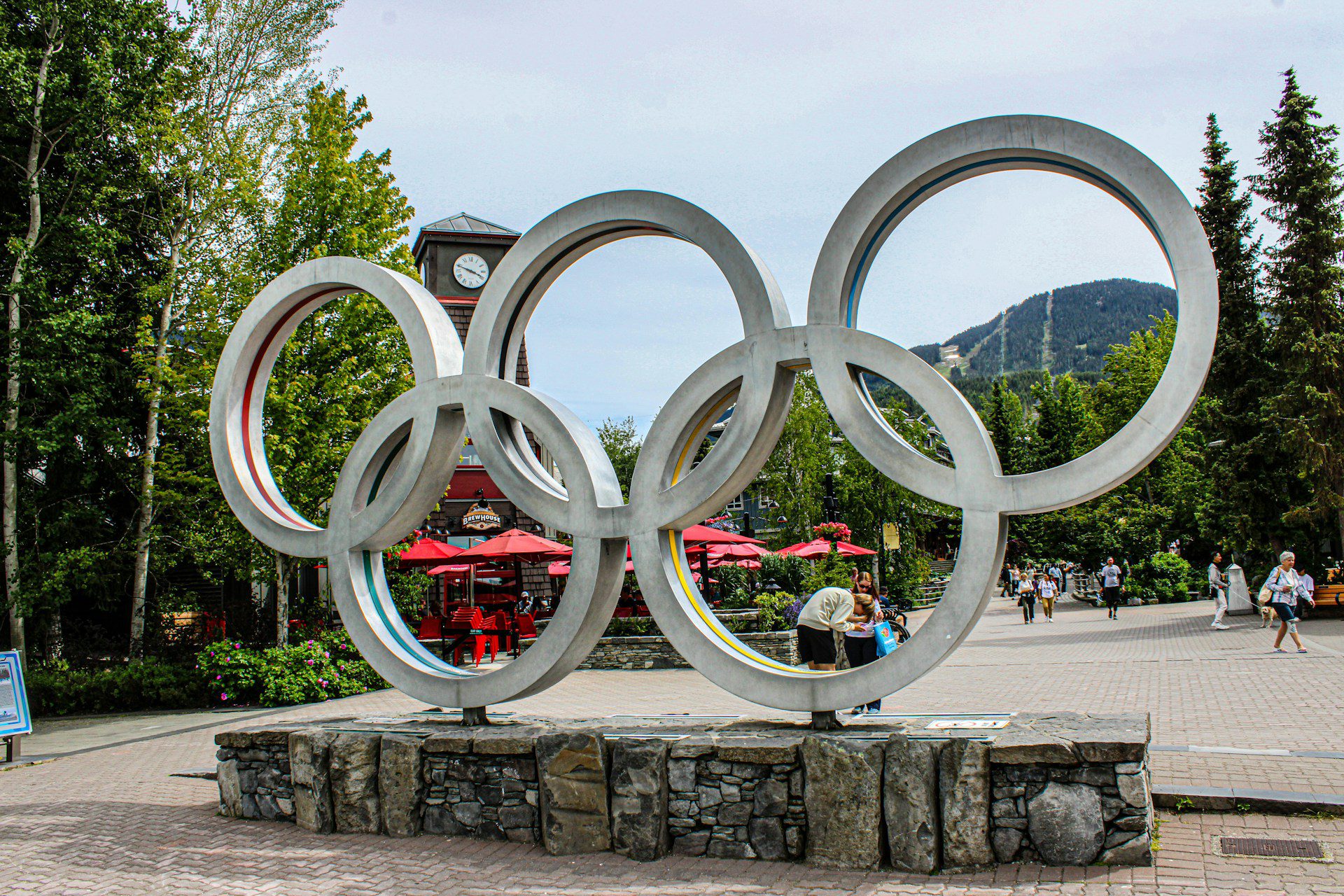

Image: Credit…Visual China Group, via Getty Images

The activists’ request was straightforward: They wanted to share their concerns about human rights in China, in particular the possibility that official merchandise for the Beijing Olympics was being made with forced labor, and to hear what the International Olympic Committee was doing to ensure it was not.

For months, they pressed Olympics officials for a conversation. At first, the I.O.C. demurred. Eventually, officials from the committee agreed to meet — but only for an “active listening exercise,” not to share any information. And the talk would have to remain secret.

Finally, late last month, the I.O.C. pulled out entirely from meeting with the activist group, the Coalition to End Forced Labor in the Uyghur Region.

“While the I.O.C. will continue strengthening its work in relation to labor rights,” said the email from Magali Martowicz, the I.O.C.’s head of human rights, “we regret to conclude that your organization and the I.O.C. will not be able to engage in a dialogue this time as a result of differences in approach, including regarding scope, process and confidentiality.”

Concerns about China’s human rights record loom over the country’s preparations to host the Winter Olympics in Beijing next month. World leaders and activists have focused on the authorities’ suppression of the predominantly Muslim Uyghur minority, in the western Xinjiang region, and allegations that Uyghurs are being pressed into forced labor. The United States, Britain, Canada and Australia have announced diplomatic boycotts.

The I.O.C. has consistently deflected calls to exert more pressure on China — a lucrative market and an important financial and organizational partner for the Olympics — for its potential abuses. When Peng Shuai, a three-time Olympian, disappeared from public life after accusing a top Chinese leader of coercing her into sex, the I.O.C. held a video call with her and said she appeared to be safe, despite widespread global concern. When challenged on China’s suppression of civil liberties in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Tibet, officials have argued that the Games are not political.