Exported and Exposed Abuses against Sri Lankan Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates

I. Summary

Even if I went to bed at 3:30 a.m., I had to get up by 5:30 a.m… I had continuous work until 1:00 a.m., sometimes 3:00 a.m…. Once I told the employer, “I am a human like you and I need an hour to rest.” She told me, “You have come to work; you are like my shoes, and you have to work tirelessly.”

The conditions were getting worse. I told the employer that I wanted to leave but she would not take me to the agency…. [Her husband] would say, “You want to go, you want to go?” and he would pull my hair and beat me with his hands. He went to the kitchen and took a knife and told me he would kill me, cut me up into little pieces, and put the little pieces of me in the cupboard… By this time they owed me four months’ salary….

There are more and more innocent women going abroad, and planning to go. It is up to the women to care of themselves. The [Sri Lankan] government gets a good profit from us; they must take care of us. They must do more to protect us. —Kumari Indunil, age 23, a former domestic worker in Kuwait

Desperate to support themselves and their families, and with few viable options at home, over 125,000 Sri Lankan women migrate to the Middle East as domestic workers each year. Their earnings have made a significant contribution to the Sri Lankan economy, yet many migrant women resort to this survival strategy at profound personal cost.

Unscrupulous labor agents and subagents in Sri Lanka often charge illegal, exorbitant recruitment fees and deceive women about their prospective jobs. In Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), labor laws exclude domestic workers, who are typically confined to the workplace and labor for excessively long hours for little pay. In some cases, employers or labor agents subject domestic workers to physical abuse, sexual abuse, or forced labor. While current figures likely underestimate the scale of abuse, the Sri Lankan government reports that 50 migrant domestic workers return to Sri Lanka “in distress” each day, and embassies abroad are flooded with workers complaining of unpaid wages, sexual harassment, and overwork.

The exploitation that migrant domestic workers confront is not secret, and the media in the region regularly carries stories of horrific abuse. This stream of news articles includes such headlines as, “Broken Finger and Wrist Bone Tell Tale of Torture,” “Lankan Maid’s Hand ‘Burnt for Cooking Tasteless Food,’” “Woman Tortured, Killed Maid for Being ‘Lazy,’’’ and “Lankan Housemaid ‘Forced to Eat Pet Cat’s Food.’”1

Despite this awareness, the governments of Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon, and the UAE have failed to extend even standard labor protections to these workers. Sri Lanka has yet to rein in a competitive and corrupt recruitment industry, and has not created adequate support services or effective complaint mechanisms for abused workers. The countries of employment have balked at guaranteeing rights that all other workers enjoy, including rest days, limits on working hours, and in some countries, a minimum wage.

Labor migration is extremely lucrative for Sri Lanka. In 2006, Sri Lanka’s mobile labor force brought in US$2.33 billion in remittances—more than 9 percent of the gross domestic product and US$526 million more than the country received in foreign aid and foreign direct investment combined. Remittances are now a greater source of revenue than tea exports, Sri Lanka’s second most important commodity export (after apparel). Labor migration relieves unemployment in Sri Lanka and serves as a crucial source of foreign exchange for the island.

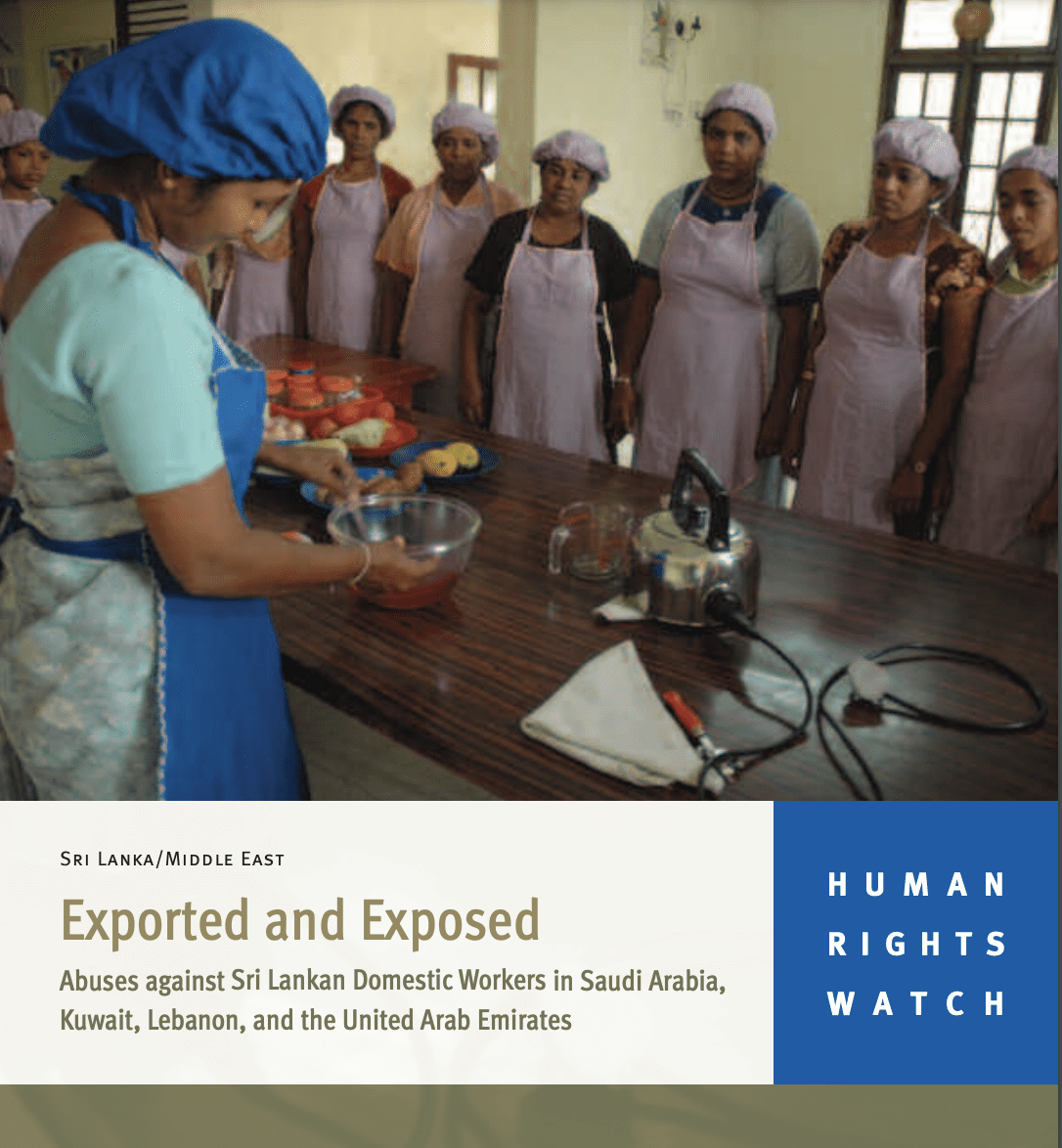

Because remittances are critical to the Sri Lankan government’s strategy for poverty reduction and lowering its trade deficit, the government actively pursues a policy of foreign employment promotion. Despite recent reforms, described below, these policies often lack a human element, treating migrant women as an export commodity marketed to wealthy, oil-producing countries where demand is high, yet falling short on human rights protections. Migrants’ rights groups in Sri Lanka have referred to the Sri Lankan government’s approach to its migrant workers as the “commodity supply approach,” characterized by the formula “select, train, pack, insure, and export,” with the imperative to protect workers noticeably absent.

Migration holds both risk and promise, and migrant women have experienced both abuse and success. Supporting an average of five family members back home, women workers migrate with the often illusory promise of earning as much as ten times more than they earn in Sri Lanka. With wages earned abroad, migrant domestic workers have built homes, started businesses, supported elderly relatives, and purchased children’s school books and uniforms. Many female migrant domestic workers have become the primary wage earner for their family, gained enhanced status in their families and communities after their return, and enjoyed increased decision-making power in the family and control over family resources.

The Sri Lankan government’s policies have improved over recent years and it deserves credit for initiating important steps to manage the outflow of migrant workers and to start providing protections. The government of Sri Lanka set up an institutional structure, the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE), in 1985 to ensure workers migrate through legal channels, minimize corruption and exploitation by recruitment agencies, and facilitate the flow of workers’ remittances. Yet significant gaps in protection remain.

The migration industry that has developed to facilitate Sri Lankan women’s labor migration is rife with irregularities that expose prospective domestic workers to the threat of later abuse. Unscrupulous labor agents and their unlicensed and unregulated subagents charge illegal and exorbitant fees to prospective migrant domestic workers for job placement services and other migration-related costs, charging fees that are triple or quadruple officially sanctioned rates. Domestic workers often incur heavy debts at usurious interest rates to cover these fees, circumscribing domestic workers’ options when they face abuse. Labor agents and subagents often deceive women about the country where they will work, their conditions of employment, and the salaries they will receive. These deceptive recruitment practices place migrant domestic workers at risk of exploitation after they migrate to the Middle East.

Migrant domestic workers are among the least protected workers of the labor force. They work in an unregulated and undervalued job sector, and they are at high risk of abuse and exploitation. In Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon, and the UAE, Sri Lankan women domestic workers face a range of abuses and forms of exploitation, many of which are gender-specific. Our research shows that they face pervasive workplace abuses: they generally work excessively long working hours, get no rest days, and are paid discriminatory wages, including earning less than their male migrant counterparts. In these four labor-receiving countries, Sri Lankan women domestic workers also suffer physical, psychological, and sexual abuse; nonpayment of wages; food deprivation; confiscation of their identity documents; forced confinement in the workplace; and limitations on their ability to return to their home countries when they wish to do so. In some cases, the combination of these pervasive workplace abuses create a situation in which women workers are trapped in forced labor.

Countries of employment in the Middle East admit migrant domestic workers as short-term contract laborers and accord them few rights. The labor laws of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon, and the UAE categorically exclude migrant domestic workers from protection. The governments of those countries deny migrant domestic workers equal protection under their country’s laws and limit their ability to change employers, even in cases of abuse.

This lack of legal protection, and limitations on women’s ability to vindicate their rights equally under the law when they seek remedy, compounds the violations women experience. Without clear legal rights and excluded from the protection of existing labor legislation, domestic workers have little recourse when they experience abuse or exploitation. Workers who seek assistance from the authorities to hold abusive employers accountable or recover unpaid wages often receive little or no protection and encounter numerous legal and practical obstacles to obtaining redress. Trapped by immigration policies that limit their ability to change employers, with nowhere to turn for help, many migrant domestic workers are unable to escape from abusive work situations and must endure ongoing abuse.

Largely excluded from local justice mechanisms, migrant domestic workers sometimes flee to their embassies or consulates in the countries of employment in a desperate bid for assistance. Sri Lankan migrant domestic workers who are able to flee their employers often end up living in poor, overcrowded conditions in Sri Lankan embassies and consulates. Women we spoke with told us that Sri Lankan consular officials often provide little or no assistance to domestic workers who approach them with cases of severe physical abuse, sexual abuse, unpaid wages, or exploitative working conditions. Domestic workers returning to Sri Lanka said they confronted obstacles to filing complaints and obtaining victim services.

Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon, and the UAE are failing to uphold their international human rights treaty obligations. To reduce domestic workers’ exposure to abuse when they migrate, the Sri Lankan government must do more to provide prospective domestic workers with information about their rights before they migrate, monitor and regulate labor agents and their subagents, provide fuller support to domestic workers at embassies and consulates in times of crisis, and enhance redress mechanisms and services provided to domestic workers upon return to Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka’s ability to protect prospective domestic workers and to assist migrant women in times of crisis depends heavily on the cooperation of the countries of employment. Increased cooperation between the Sri Lankan foreign missions and the countries of employment is necessary to arrange rescue of domestic workers in distress, create effective complaints mechanisms, and to craft and enforce mutually recognized contracts that provide real protections.

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in Sri Lanka in October and November 2006, and in Saudi Arabia in November and December 2006, and was in contact with numerous sources since that time. This report is based on in-depth interviews with 100 women migrant domestic workers. In Sri Lanka, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with 80 migrant domestic workers who had returned to Sri Lanka from the Middle East in the past 14 months. These women had worked in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon, and the UAE. Thirty-nine of these 80 migrant domestic workers interviewed had worked in more than one country in the Middle East, including Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and Jordan. Human Rights Watch interviewed migrant domestic workers in seven of the eight districts with the highest concentration of returned migrant domestic workers in Sri Lanka: Colombo, Kalutara, Kegalle, Kurunegala, Gampaha, Kandy, and Galle, as well as in Nuwara Eliya. In Saudi Arabia, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with 20 Sri Lankan migrant domestic workers. With a few exceptions, expressly noted in the footnotes, the names of domestic workers cited in this report have been changed to protect their identity.

In Sri Lanka, Human Rights Watch also interviewed nongovernmental organization activists and service providers; trade union leaders; and labor agents and subagents, including leaders of the Association of Licensed Foreign Employment Agencies (ALFEA). We also met with government officials, including officials from the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment, Ministry of Labour, Ministry of Foreign Relations’ consular division, Department of Immigration and Emigration, Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, and the Legal Aid Commission. In Saudi Arabia, Human Rights Watch interviewed three Sri Lankan embassy and consular officials, and conducted 12 individual and group interviews with Saudi government officials, including Labor, Social Welfare, Foreign Affairs, Prison, and Police officials.

Read more here.