Crackdown in Cambodia: Workers Seeking Higher Wages Meet Violent Repression

On January 2 and 3, 2014, Cambodian security forces engaged in deadly attacks on protesting garment workers in the country’s capital, Phnom Penh. The country’s military police killed at least four people and injured at least 38 by firing assault rifles at workers who were protesting outside garment factories, demanding higher wages. According to the country’s leading human rights organization, the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (known by its French acronym, LICADHO), military police fired at workers with live ammunition for a prolonged period with no apparent effort to avoid inflicting injury or death. Those killed included workers employed at factories supplying a number of major international brands and retailers, including Walmart, Hudson Bay, Sears, Abercrombie and Fitch, Nike, Russell, adidas, Puma, Uniqlo, HanesBrands, Primark, and Marks & Spencer.3

The deadly assault was a response to strikes and demonstrations by tens of thousands of garment factory workers calling for a wage adequate to meet their basic needs. The protests were sparked when the Cambodian government announced a new minimum wage in December 2013, and the increase declared fell below the widely publicized assessment, by an official tripartite body, of the wage workers actually need to meet their basic needs.

The recent wave of protests is not the first time that Cambodian apparel workers have walked out of factories in protest over the rock-bottom wages paid by the country’s garment industry, which are the world’s second-lowest ‒ above only those in Bangladesh ‒ among major apparel-producing countries. Indeed, wages in Cambodian garment factories are so low that workers often experience significant difficulties meeting their minimum nutritional needs, a factor that has been linked to the literally dozens of episodes of mass fainting in apparel plants over the past several years that have affected several thousands of workers.

Nor were the killings on January 3 the first time that Cambodian authorities have responded to garment worker protests with deadly violence. Instead, this was the third such shooting incident in as many years, following a February 2012 incident at factory supplying Puma, where a government official shot three protesting workers, and shootings by military police last November of ten persons, one fatally, at a march by striking workers from a plant supplying Levi-Strauss, Gap and H&M.

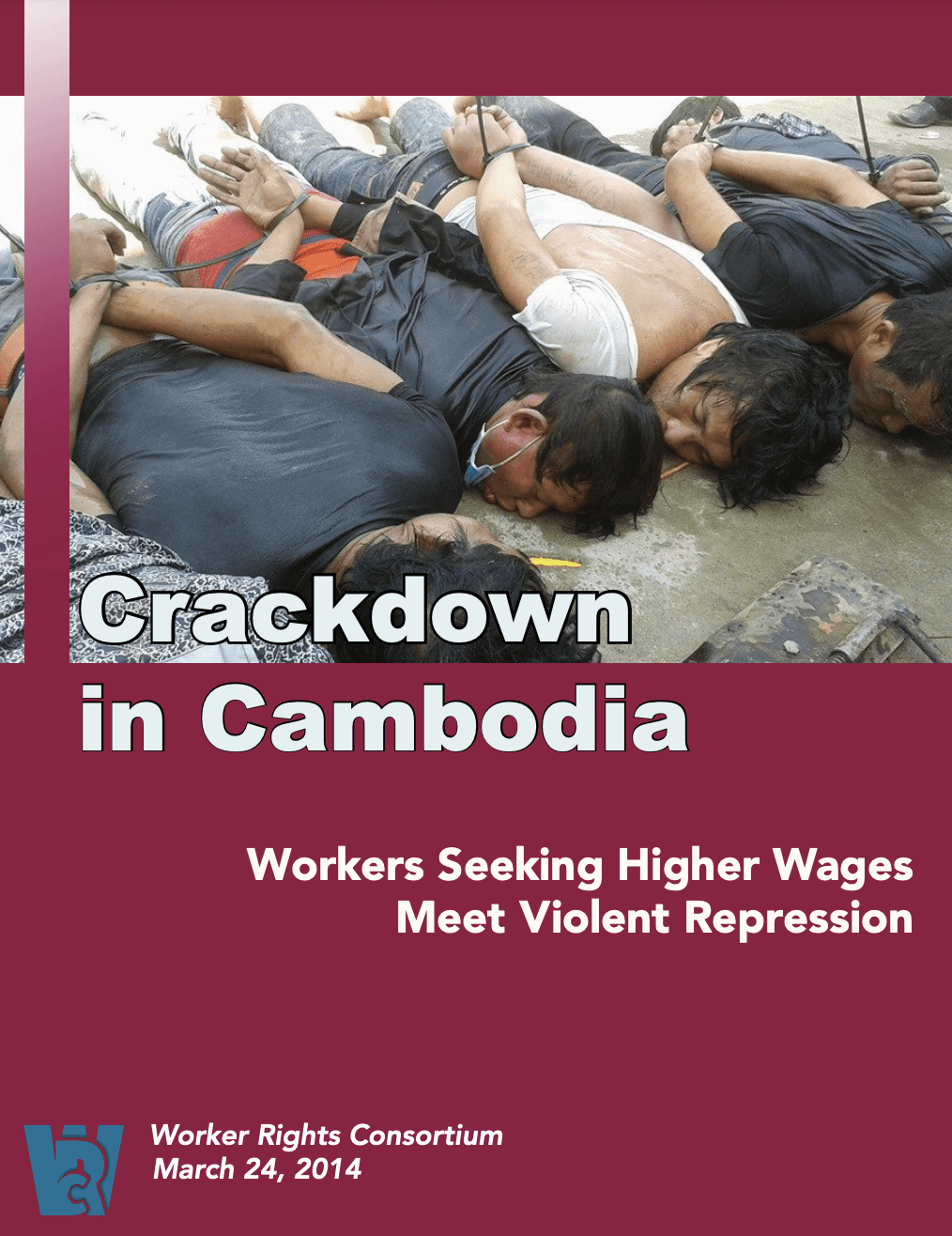

Since the shootings at the beginning of this year, repression of Cambodian garment workers’ fundamental human and labor rights of assembly, association and free speech has continued with little respite. During the past two months, state authorities have banned public gatherings completely, and still continue to hold 21 workers detained during the January crackdown. The individuals in detention, who reportedly were beaten after being seized by authorities, include workers employed by factories supplying Nike, Team Edition (Footlocker), PVH, Polo Ralph Lauren, Costco, Bloomingdales, Dillard’s, and Clark’s Footwear. Security forces have continued to put down any sign of worker protest, violently dispersing a peaceful demonstration by factory employees on January 26 using smoke grenades and electric batons;10 and the Ministry of Labor has blocked the legal formation of unions, refusing to register any newly-established unions.

The most direct responsibility for both the needless loss of human lives on January 2 and 3 and the repression of human and labor rights that followed clearly falls on the Cambodian government. However, Cambodian factory owners also are deeply implicated in this violent campaign against garment workers’ call for higher wages, as are their business partners ‒ the leading US and European apparel companies that obtain the greatest profits from these workers’ labor. Neither the massive protests by workers in December nor the violent repression by security forces in January likely would have occurred had not Cambodian factory owners feared that by acceding to workers’ wage demands they would render themselves unable to meet pricing requirements of Western brands and retailers.

The price squeeze confronting Cambodian garment factory owners ‒ between the demands of brands and retailers for cheap apparel and the demands of garment workers for livable wages ‒ explains not only why the industry has so aggressively opposed a significant increase in the minimum wage (even though real wages for Cambodian garment workers are no higher today than they were in 2000), but also why, since the mass protests erupted, industry leaders have tended to support escalation and confrontation over a negotiated settlement between labor and management. To cite just one example of this tendency, when workers at some factories launched a strike in mid-December in support of a higher minimum wage, the factory owners’ organization, the Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia (GMAC) called for, in effect, a nationwide lockout of the industry’s workers by its members, dramatically expanding the dispute.

Even more egregiously, in the week leading up to the crackdown, factory managers, in particular, those from certain factories with owners based in South Korea, specifically lobbied elements of the Cambodian military to intervene against the worker demonstrations, both directly and through the South Korean embassy. This military intervention at the request of factory owners, which was conducted by not only military police, but also combat units with a track record of human rights abuses, was a proximate cause of the deaths, beatings and illegal detentions suffered by Cambodian garment workers on January 2 and 3.

Nor have factory owners been reluctant to take action, themselves, to punish garment workers and worker representatives for calling for a livable wage. Since the wage strikes and protests began in December, garment factories have terminated 168 workers who are members and leaders of plant-level unions. The GMAC has filed lawsuits against the elected leaders of several national labor federations representing garment workers for their involvement in the strike, seeking damages for lost profits and alleged property losses.14 And, today, military personnel are stationed on the very premises of factories in the same area where security forces killed and detained workers during the January crackdown.

The Cambodian garment industry’s ongoing refusal to pay its workforce a minimally adequate wage ‒ a refusal, in effect, dictated by the business practices of Western brands and retailers ‒ has resulted in the worst episode of state violence and repression against civilians in Cambodia in more than a decade. The January shootings have been broadly denounced by international governmental and nongovernmental organizations including the United Nations (UN),17 the International Labour Organization (ILO), Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch (HRW). On January 9, 2014, Brad Adams, Asia Director for HRW, stated that, “[T]he [ruling party]’s violent crackdown, abuse of detainees, and ban on all protests seem aimed to prevent the broader exercise of democratic and labor rights in Cambodia…. Diplomats and donors should vigorously protest these rights abuses if they want to prevent Cambodia from sliding further into repression.”

The same warning also holds true for apparel brands and retailers doing business in Cambodia. Indeed, HRW also called on apparel companies to “urge the Cambodian government to revoke its ban on protests and to release and drop charges against all individuals arrested for protesting for their labor rights.”

The Cambodian government’s use of deadly force and other repressive measures against protesting garment workers has created a human rights crisis that is still continuing to unfold. The WRC shares the view that apparel firms doing business in Cambodia have a responsibility to influence the government towards a nonviolent and non-repressive responsive to workers’ protests, both directly and through their Cambodian suppliers.

The current crackdown in Cambodia is a cause for serious concern on the part of universities, colleges and companies in the collegiate licensed apparel sector. Sixteen university licensees have disclosed producing collegiate apparel in Cambodia. In 2013, these licensees produced apparel at a total of 20 factories in the country.

On January 3, 2014, the WRC contacted the largest university licensees producing in Cambodia concerning the shootings of protesting workers that had just occurred that day, calling on them to help halt the looming repression of labor and human rights in the country. As detailed in this report, the WRC recommends to university and collegiate licensees and other brands and retailers producing apparel in Cambodia that they take the following measures to address the current crisis:

- Ensure that their own supplier factories do not retaliate against workers on account of the exercise of associational rights; and require them to reinstate with back pay any workers whom they have terminated in retaliation for participation in a strike, protest or other associational activity, unless employers can demonstrate that these terminations were consistent with Cambodian law and international labor standards.

- Help end the Cambodian government’s repression of worker rights, by communicating to government officials that persons who have been detained as a consequence of their participation in or association with the recent wage protests should be immediately released ‒ without condition, unless the legal standard for criminal indictment is clearly met ‒ and that, until their release, such detainees should be treated in accordance with international human rights standards.

- Call on the Cambodian government to ensure that individuals responsible for excessive use of force, especially those responsible for causing death or injury, either directly or via command authority, are disciplined and prosecuted; and ensure that adequate compensation is paid to the victims of this violence.

- Meet and negotiate with representatives of Cambodian garment workers, a written platform for addressing the underlying causes of the current crisis, including commitments to:

- Require their supplier factories in Cambodia to pay workers a minimum of $160 per month, as the wage needed to meet an individual worker’s basic needs;

- Adjust their pricing practices as needed to permit their supplier factories to sustainably pay workers the $160 per month minimum; and

- Assuming compliance with other commercial requirements, to maintain their business with factories that implement the $160 per month minimum for at least the next two years

Both the GMAC and the Cambodian government have expressed concern that significant increases in wages for garment workers will cause brands and retailers to shift orders to other countries. If university licensees and other brands and retailers make firm commitments not only to require their supplier factories to meaningfully increase wages, but also to factor such an increase into the prices they pay for garments, university licensees and other brands and retailers can play a vital role in resolving the current crisis.

The following report discusses the current human and labor rights crisis affecting garment workers in Cambodia; its relationship to the underlying issue of inadequate wages; the response of university licensees to the WRC’s recent communications to them on this subject; and the WRC’s recommendations for further action by licensees and other brands and retailers doing business in Cambodia.

Read more here.