At least four major suppliers of Hyundai Motor Co and sister Kia Corp have employed child labor at Alabama factories in recent years, a Reuters investigation found, and state and federal agencies are probing whether kids have worked at as many as a half dozen additional manufacturers throughout the automakers’ supply chain in the southern U.S. state.

At a plant owned by Hwashin America Corp, a supplier to the two car brands in the south Alabama town of Greenville, a 14-year-old Guatemalan girl worked this May assembling auto body components, according to interviews with her father and law enforcement officials. At plants owned by Korean auto-parts maker Ajin Industrial Co, in the east Alabama town of Cusseta, a former production engineer told Reuters he worked with at least 10 minors. And six other ex-employees of Ajin said they, too, worked alongside multiple underage laborers.

In two separate statements sent by the same public relations firm, Hwashin and Ajin said their policies forbid the hiring of any worker not of legally employable age. Using identical language, both companies said they hadn’t, “to the best of our knowledge,” hired underage workers.

The employment of children at Hwashin and Ajin hasn’t been previously reported. The news follows a Reuters report in July that revealed the use of child workers, one as young as 12, by SMART Alabama LLC, a Hyundai subsidiary in the south Alabama town of Luverne. In August, the U.S. Department of Labor said that SL Alabama LLC, another Hyundai supplier and a unit of South Korea’s SL Corp, employed underage workers, including a 13-year-old, at its factory in Alexander City.

Since then, as many as 10 Alabama plants that supply parts to Hyundai or Kia have been investigated for child labor by various state and federal law enforcement or regulatory agencies, according to two people familiar with the probes. The investigations are being conducted across small towns and rural outposts where many of the suppliers and the job recruiters that staff them are located. It isn’t yet clear whether the probes will lead to criminal charges, fines or other penalties, the two people said.

On Aug. 22 a team of Labor Department and Alabama state inspectors arrived unannounced at one of Ajin’s plants, according to people familiar with the operation. As the team arrived, workers rushed out the back and left the premises before they could be questioned, one of the inspectors told a meeting of Alabama’s anti-human trafficking task force last month, according to two people who attended. The inspection hasn’t previously been reported.

A Labor Department spokesman, Eric Lucero, told Reuters that the agency’s Wage and Hour Division has an open investigation into Ajin, but declined to confirm whether the probe was related to child labor.

In its statement, Ajin said it “will cooperate fully” with any investigations by regulators and law enforcement.

Hyundai, in a statement, told Reuters it “does not condone or tolerate violations of labor law” and requires that “our suppliers and business partners strictly adhere to the law.” Kia, for its part, said it “strongly condemns any practice of child labor and does not tolerate any unlawful or unethical workplace practices internally or within our business partners and suppliers.”

Hyundai and Kia, South Korea’s two largest automakers, are sister companies controlled by parent Hyundai Motor Group. Both companies told Reuters they are reviewing hiring practices used by their suppliers.

The discovery of child labor at additional plants in Hyundai’s American supply chain could deal a fresh reputational blow to a company whose fast growth and popularity in recent years has led it to become the third-largest automaker by U.S. sales. The earlier reports of child labor drew law enforcement and regulatory scrutiny to the company’s ability to meet its own professed ethical standards and comply with basic labor regulations in the United States.

In-house human rights policies, posted by both brands online, prohibit child labor at Hyundai and Kia facilities and among their suppliers, too. Alabama and U.S. law restrict factory work for people under age 16, and all workers under 18 are forbidden from many hazardous jobs in auto plants, where metal presses, cutting machines and speeding forklifts can endanger life and limb.

After the earlier reporting by Reuters on child labor at suppliers SMART and SL, Hyundai’s chief operating officer, José Muñoz, told the news agency he ordered the carmaker’s purchasing department to cease business with the suppliers named in the news reports “as soon as possible.” He also said the company would investigate all suppliers to Hyundai’s Alabama operations. Hyundai, Muñoz added, would seek to end the use of third-party staffing agencies that many of its suppliers have relied upon to vet and hire workers.

Hyundai is now backing away from Muñoz’s remarks.

In its recent statement to Reuters, Hyundai said it has canceled its plans to cut off suppliers where minors have worked. Two of its suppliers, SMART and SL, have taken “corrective actions” to fire staffing agencies they found problematic, it said. Noting the “important economic role” that parts makers play in many small Alabama towns, Hyundai added, “additional oversight is a better course at this time than severing ties with these suppliers.”

Hyundai declined to make COO Muñoz available for a follow-up interview.

The use of third-party staffing agencies is a common practice among manufacturers and other labor-intensive sectors throughout the United States. The tactic has long been criticized by labor activists because it gives factory owners and other employers the ability to outsource responsibility for the screening, hiring and regulatory compliance of their workforces.

Earlier this year, Reuters showed how staffing agencies in rural Alabama recruited undocumented workers from Central America, including minors who had entered the U.S. without parents or guardians, and supplied them to chicken processing plants. As with those minors, at least some of the children who worked at Hyundai suppliers used false identities and documentation obtained through black-market brokers, sometimes with the help of staffing firms themselves.

To understand how child labor took root in the supply chain of one of the world’s most successful automakers and in the job market of the world’s richest country, Reuters interviewed more than 100 current and former factory workers and managers, labor recruiters, state and federal officials, and others. Reporters spent weeks around auto parts factories in rural Alabama and reviewed thousands of pages of court records, corporate documents, police reports and other records.

“It’s shocking,” David Weil, a former administrator of the Wage and Hour Division of the Labor Department, said of the signs of widespread child factory work. “The ages involved, the danger of what they are being employed to do, it’s a clear violation.”

Across Alabama, a sprawling and partially interconnected network of suppliers and staffing agencies, many Korean-owned, exists to serve the Hyundai brands. Hyundai operates an assembly plant in Montgomery, the state capital. Kia builds cars across the state line in West Point, Georgia. Both states, so-called “right to work” jurisdictions whose laws allow workers to reject unions and thereby undercut the power of organized labor, have attracted numerous automakers and follow-on investments, as recently as this year, granting them billions of dollars in tax breaks and other incentives along the way.

A key element of Hyundai’s supply network is its ability to provide “just-in-time” delivery of parts, a staple of modern manufacturing meant to minimize stockpiles of materials. To avoid halting assembly lines, Hyundai can fine suppliers – sometimes thousands of dollars per minute – for any delay, according to people familiar with its operations. Pressure to deliver, several current and former employees at suppliers told Reuters, intensified in recent years because of the labor and supply shortages that crippled manufacturers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The struggle to meet demand, labor law experts say, has increased chances that employers cut corners to keep assembly lines staffed, whether employees are legally allowed to work or not. “It seems like the stage was set for this to happen,” said Terri Gerstein, director of the state and local enforcement project at Harvard Law School’s Labor and Worklife Program. “Plants in remote, rural areas. A region with low union density. Not enough regulatory enforcement. Use of staffing agencies.”

“It’s shocking. The ages involved, the danger of what they are being employed to do, it’s a clear violation.”

The shortage of labor across manufacturing, and the low pay offered by some plants and agents for factory jobs, often attract job candidates most pressed for work – particularly undocumented migrants and minors. “When you have workers who are desperate for jobs and they’re not empowered and you have a lot of competition, you often see a race to the bottom,” said Jordan Barab, a former deputy assistant secretary at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the federal workplace regulator.

So far, SL, the manufacturer in the central Alabama town of Alexander City, is the only Hyundai or Kia supplier charged with violating child labor laws. On Aug. 9, state and federal labor and law enforcement officials found seven workers between the ages of 13 and 16 on the SL factory floor, according to people familiar with the operation and government documents.

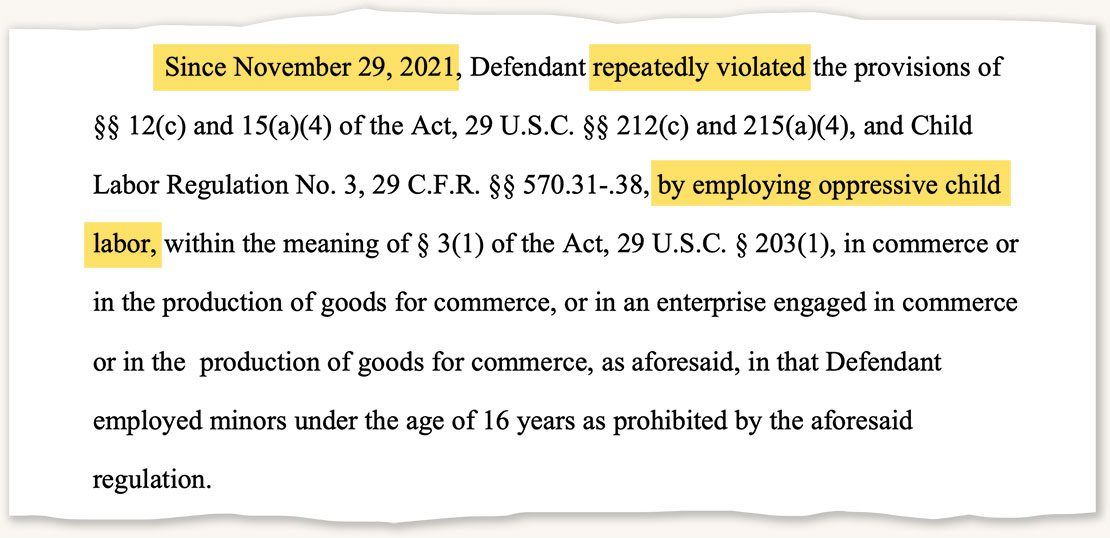

The U.S. Labor Department in a court filing said SL Alabama had “repeatedly violated” the law “by employing oppressive child labor.” It fined the company about $30,000. Alabama’s Department of Labor fined SL and one of its staffing agencies a total of about $36,000.

SL told Reuters in October it was cooperating with investigators and auditing its employment policies. The company said it had terminated the staffing agency fined by Alabama labor regulators and fired the president of SL’s Alexander City plant. The plant’s former president couldn’t be reached for comment.

Among the children found working at the plant, Reuters learned, were two Guatemalan brothers, aged 13 and 15, who were taken into protective custody by federal authorities. While they worked at SL, the brothers lived without their parents, staying with other factory workers in a sparsely furnished house owned by the president of the staffing agency that hired them, according to property records, family members, and a former coworker interviewed at the home in Alabama.

A teenage cousin who worked at the factory with the brothers said that no one at SL ever verified workers’ ages. “They didn’t ask any questions,” the cousin said. Reuters isn’t naming the cousin and other minors and undocumented migrants interviewed for this story, but confirmed their identities and local employment history with authorities.

Since Reuters’ first report on child labor in Hyundai’s supply chain, staffing firms have fired foreign workers from at least five factories, current and former employees said, particularly any who appeared too young to legally work in the plants. The dismissals make it harder for authorities to investigate, officials said, because the employees may have been working under aliases and some moved away after being fired.

“NOW HIRING”

Hyundai opened its massive Montgomery vehicle assembly plant in December 2005. The Georgia Kia factory, 100 miles to the east, opened five years later. To support the two brands, many of Hyundai’s suppliers from Korea set up in the area, building parts factories that revived local economies. Hyundai and Kia now have dozens of suppliers in Alabama, according to the Economic Development Partnership of Alabama, a business group.

Authorities first caught wind of child labor among automotive suppliers in early 2021. A school official in Alabama’s rural Butler County told state officials that some children – including at least one immigrant girl around 12 years old – appeared to be working at Hwashin, the parts maker in Greenville. The manufacturer, which builds metallic body parts in a factory the size of four football fields, is now the biggest employer in a town once better known for cotton farming.

After the tip, officials familiar with the matter told Reuters they began examining Hwashin. The tipster and the officials spoke on condition they not be identified by name or by agency.

Even as authorities were investigating, a 14-year-old migrant was recruited to the factory floor at Hwashin. The girl’s father said he and his daughter arrived in Alabama four years earlier, after a long trek from Guatemala. The teen looks younger than her age. On a visit to their home, a small house shared with other migrants south of Greenville, Reuters met the girl, who is just over four feet tall, with rosy cheeks and a timid smile.

Early this year, the father had been working poultry jobs. Troubled by the family’s meager income and hoping to send money to family back in Central America, the girl, who wasn’t attending school, asked her father if she too could get a job, he said. He agreed. “I wish I had said no,” he said.

In April, the father turned to a Spanish-speaking recruiter who was regularly seeking laborers. The recruiter, the father said, worked for a company he knew as JSS, a name familiar in the area as a staffing agency for Hyundai suppliers. Reuters was unable to reach the recruiter.

As with many staffing firms, the ownership structure of JSS isn’t entirely clear in public records. A review of more than two dozen labor brokers found a complex web of overlapping companies that form and dissolve quickly to serve Hyundai suppliers.

Two other people, speaking on condition of anonymity, told Reuters they had worked as recruiters for JSS. The agency, they said, hired underage workers while they worked there. Those former recruiters gave Reuters an address in the state capital and said that JSS’s top executive, Jae Kim, often worked there.

In October, Reuters visited the office, located in a Montgomery strip mall. Inside, paperwork and logos for various agencies, including “JSS Staffing,” lay on desks. Javier Martinez, an employee, confirmed in a brief interview that the office is run by a businessman named Jae Kim. He said Kim wasn’t in that day.

On LinkedIn, Jae Kim is listed as chief executive of a staffing firm called Advanced Job Solutions LLC, or AJS. Kim didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

In Greenville, three miles from the Hwashin factory, a storefront for “JSS Staffing” advertised jobs this month in a big window display in Spanish and English. “Estamos contratando!” the sign reads. “NOW HIRING.” A property manager for the site said the office is rented to a company known as Job Supply System LLC.

In a phone call to the Greenville office, an attendant referred Reuters back to Martinez, the employee at Kim’s office in Montgomery. Martinez told Reuters by email that he was responding on behalf of Job Supply Systems Alabama LLC, or JSSA – a slight variation on the name of the company renting the Greenville office. Despite the overlap, the firms are different entities, Martinez wrote. Reuters couldn’t determine if the agencies shared ownership, management structure or any common history.

“JSSA is not affiliated with and has no involvement in the management or operations” of Job Supply System, Martinez wrote. JSSA’s policy, he wrote, is “not to hire, employ, or refer any minor for employment.” The company, he added, was aware of ongoing child labor investigations and “has complied with requests from investigators.”

When the Guatemalan girl’s father contacted the recruiter, he said he asked whether his daughter’s age would be an issue. No, the recruiter told him. On the black market, the girl’s father procured a fake ID, seen by Reuters, that says she is an 18-year-old California resident. The name and picture on the card are the daughter’s, but the birth year is phony.

By May, the father said, he and his daughter were both working at Hwashin, each earning about $11 per hour. That’s higher than the federal minimum wage of $7.25 – Alabama doesn’t impose a state minimum. But the rate is below what many other industrial jobs in the region pay, including poultry processors, where workers usually earn at least $14 per hour.

Father and daughter worked long shifts, commuting 90 minutes each way from their home, the cost of van rides deducted from their weekly pay, the father said. Many staffing agencies operate van fleets and provide transportation to companies for which they recruit labor.

Shortly after father and daughter started, word circulated among factory workers that authorities were planning a crackdown on migrant child labor. It isn’t clear what prompted the rumors. But months earlier, another young girl from Guatemala, who worked at SMART, the Hyundai-owned supplier in nearby Luverne, disappeared briefly with an adult coworker. That girl’s case was detailed in Reuters’ first report about child labor among Hyundai suppliers.

By late May, the father said, his daughter and other minors working at Hwashin were abruptly fired by the staffing agency. “You’ve got to leave,” he said the recruiter told his daughter and other dismissed minors. “The authorities will be arriving here soon.”

The father said he also left Hwashin by early June. At that time, investigators hadn’t appeared. Reuters couldn’t determine whether authorities have visited the plant since. Hwashin said it isn’t aware of any probe of its labor practices and that it would cooperate with any investigation.

“It was obvious there were minors”

Some adult factory workers in Alabama’s Hyundai supply chain told Reuters they knew or suspected that children worked alongside them, but feared raising the issue would cost them their jobs.

Raul Roa, a 27-year-old production engineer from Mexico, had arrived in 2020 at the east Alabama town of Cusseta to work at Ajin, one of the two metal stamping plants owned by the Korean parent company of the same name. Roa said Ajin, working with a recruitment firm, secured him a TN visa. The visa, a type of entry permit authorized by a trade agreement with Mexico and Canada, allows highly skilled professionals from those countries to work in the United States. Roa was among many Mexican professionals recruited by Hyundai suppliers in recent years, according to interviews, court records, and company documents reviewed by Reuters.

Shortly after his arrival, Roa said, he began noticing a significant increase in the number of migrant workers recruited locally. Among them, he suspected, were minors. With time, he got to know some of the younger workers. At least 10 told him they were underage, he said, most of them just 15 or 16 years old.

“I was very surprised,” said Roa, who left Ajin earlier this year for a job outside the automotive industry. “It was my first job in the United States and this is not what you would expect to see here.”

Six other former workers told Reuters they, too, saw underage workers at Ajin’s two factories in Cusseta. All six spoke on condition that they not be identified.

One of the six former workers, an American manager at one of Ajin’s plants, told Reuters he did alert superiors last year to the presence of workers who looked underage. A boss at the plant, he said, dismissed his concerns and advised him to “focus on production.”

Reuters was unable to reach the superior. Ajin declined to comment on the manager’s assertion that a superior had ignored his concerns.

At SMART, Carlos Herrera, a 29-year-old production engineer, said he heard a similar message.

Like Roa, the Ajin employee, Herrera said he had been recruited by SMART directly from Mexico with a TN visa. After starting at SMART in October 2020, Herrera said he noticed at least 20 young boys and girls working at the plant, many of them from Guatemala. He said some of the minors told him they were between the ages of 12 and 16. They worked under fake names, Herrera said, and did the same jobs as adults, some of them even driving forklifts and operating welding equipment.

In January, Herrera said, he saw a 16-year-old forklift driver sprain his hand after a fall. Another teen, he said, also fell around that time and injured his elbow. Herrera said he raised concerns about the underage workers with managers at SMART, but was brushed off. “I would tell them: This person shouldn’t be working,” he said. “But they didn’t care.”

SMART, in a statement provided by the same public relations firm hired by the other parts makers, said it cut ties with a staffing agency that supplied it with one underage worker. It said it was “unaware of any evidence” that any other firm had supplied “an employee who was not of legally employable age.” SMART didn’t respond to questions about the injuries Herrera said he saw minors incur at its plant.

SMART makes interior components for popular Hyundai models including the Santa Fe and Elantra, and is majority-owned by the carmaker.

Herrera said on several occasions he saw personnel from Hyundai visit the plant. Other former SMART employees also told Reuters Hyundai officials regularly visited the factory. The officials, wearing shirts that bore Hyundai logos, inspected the assembly line even as underage workers labored there, Herrera said. “I don’t know if they were paying attention to people’s faces,” he said, “but it was obvious there were minors.”

Hyundai didn’t respond to questions about the company’s visits to SMART or whether its officials saw underage workers there.

Herrera left SMART earlier this year and is in the process of joining a class action lawsuit filed by a group of TN visa holders against the company and several recruiting firms. The workers allege SMART and its staffing agencies recruited them abroad to come work as engineers but instead assigned them to rote assembly work at the factory. SMART in court documents has called the suit baseless.

After Reuters documented the disappearance of the young girl who worked at SMART, a team of state and federal authorities conducted the Aug. 9 inspection at SL, in Alexander City. They discovered seven minors there, including the two Guatemalan brothers, among employees making lights and mirrors for Hyundai and Kia. Alabama’s Department of Labor fined SL and JK USA Inc, a staffing agency, $17,800 each.

A state penalty letter against JK is addressed to a top executive of the staffing agency: “Sam Hong – President.” Alabama property records show the house where the two brothers lived with other SL workers is owned by a company registered in Sam Hong’s name. By email this week, Hong said JK is conducting an “internal investigation.” He declined to answer detailed questions about the penalty and the company’s hiring practices.

On a Tuesday afternoon in October, Christi Richardson, identified on JK’s website as the manager of the firm’s Alexander City branch, was packing boxes in the office, located in a small house with a red door. She told Reuters she was closing down the office, and declined to comment further. JK’s website is no longer online.

A 4-minute drive away, Reuters visited a ramshackle gray house where the young Guatemalan brothers lived earlier this year. An adult former colleague there said he had been working at the SL plant alongside the boys the day the inspectors came. Wearing a blue, long-sleeve shirt with the JK logo, the man, also Guatemalan, said he no longer worked at SL. The day after the kids were found at the plant, he said, SL managers asked all remaining workers to present legitimate documentation. He didn’t have proper papers, he said, but soon got a job at another automotive plant nearby.

In a statement provided by the same public relations agency, SL told Reuters it had ended its relationship with JK. The staffing agency, it added, provided underage workers without SL’s “knowledge, awareness, or consent.”

Both of the young Guatemalan brothers crossed the southern U.S. border alone last year, said family members and an official familiar with their entry. They are now at a shelter in Kansas operated by the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement, or ORR, according to government documents and interviews with family members. The agency, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, houses unaccompanied children after they have entered the United States. A spokesperson said the agency can’t comment on cases involving migrant minors.

Among the issues state and federal investigators are now probing is whether children who worked among Hyundai suppliers may have gotten there through human trafficking networks, three people familiar with the investigations said. “Minor is part of a child labor trafficking case,” read notes reviewed by Reuters from one of the brothers’ ORR case files.

In the notes, authorities wrote the children described “exploitation from debt bondage (repaying smuggling debts).” They added that an unnamed “third party labor service company” made the youths believe it could have them removed from the United States.

“Some children expressed fear of deportation based on comments made by company officials to them,” the notes said.