Briefing: Disposable Workers the Future of the UK’s Migrant Workforce

In December 2018, the UK government published its immigration white paper, outlining its plans for the UK’s future immigration system.3 The immigration white paper includes two TMPs:

- A Seasonal Workers Pilot to bring a limited number of temporary migrants from outside the EEA4 to come and work in UK agriculture for six months within any 12-month period

- A 12-month scheme, as a transitional measure, to bring workers “at any skill level” from specified “low-risk” countries to come and work in the UK for a maximum of 12 months without the possibility for immediate extension.

Lessons from other TMPs around the world and historically within the UK show that migrant workers are at higher risk of abuse or exploitation due to common risks in these schemes’ designs, including: lack of access to public funds, restrictions on migrant workers’ movement within the labour market, language barriers amongst temporary workers, lack of knowledge of local labour law and lack of localised support, such as trade union membership. In recognition of these real and substantial risks to temporary migrant workers, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) – the United Nations agency which oversees the Forced Labour Convention – has cautioned that “the proliferation of temporary migration schemes should not lead to the curtailment of the rights of migrant workers.”5 Due to the welldocumented abuses under TMPs, introducing such schemes risks creating a two-tiered labour market in the UK with citizens and those on longterm visas on the upper tier, with access to a full range of labour rights and state support, and temporary migrant workers on the lower tier with limited access to support for tackling poor working conditions and, as a result, left at a high risk of abuse and exploitation.

TMPs are significantly more restrictive than free movement, which grants EEA migrants the same employment rights as citizens, pathways to settlement and family reunification, and the possibility of switching jobs and moving freely from one sector to another. Under free movement, qualifying EEA nationals have access to tax credits and welfare benefits such as social housing and job seekers’ allowance, which makes it easier to leave exploitative working or living situations, including situations of domestic violence, without fear of destitution.6 EEA nationals also have the option of taking up or combining part-time and short-term work, a strategy for supplementing income in lowwage, seasonal or precarious jobs, or balancing paid work with unpaid care responsibilities. The TMPs with which the government is proposing to replace free movement are much more restrictive, being time limited, without entitlements to “public funds or rights to extend a stay, switch to other routes, bring dependants or lead to permanent settlement”.7

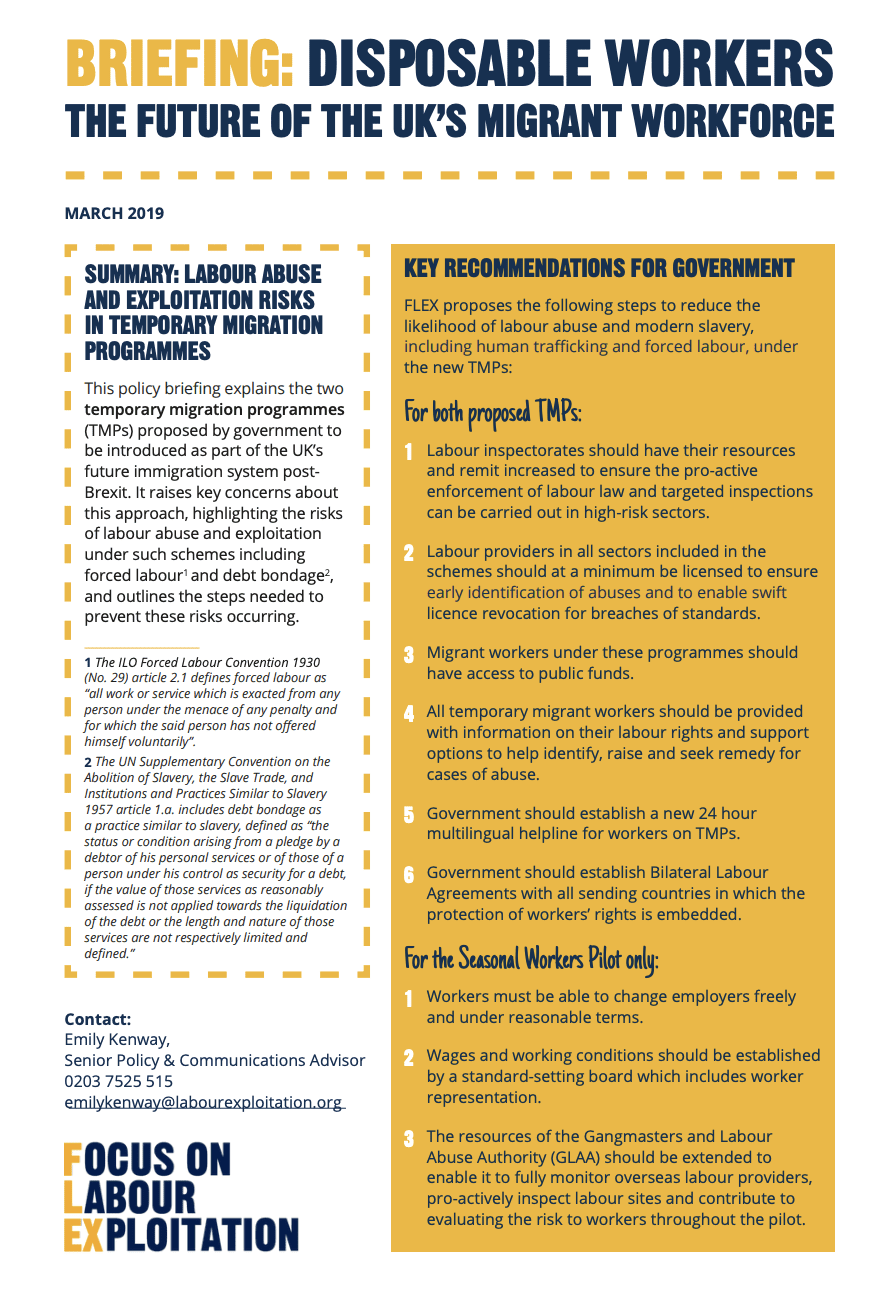

FLEX does not support migration policy which serves to limit the rights of migrant workers, thereby placing them at risk of abuse and exploitation. In doing so, FLEX is fully committed to assisting the UK to meet the aims of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 8.8 which calls for all countries to “protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers”8. Therefore, this paper engages with the TMPs as set out in the immigration white paper but calls into question how migrant workers’ labour rights can be upheld as the schemes are currently conceived, making strong recommendations for change in order to prevent their abuse and exploitation.

Read more here.