A committee studying racism in the Alabama Constitution gave tacit approval Wednesday to a plan to remove language on school segregation, poll taxes, and involuntary servitude.

The Committee on the Recompilation of the Constitution did not take a formal vote on the proposal from Othni Lathram, the director of the Legislative Services Agency. But no member of the committee raised objections to it.

“I’m reading today’s action as that the committee is generally comfortable with the direction on racist language,” Lathram said.

Lathram’s proposal would:

- Alter the state prohibition on slavery to remove a clause allowing involuntary servitude “for the punishment of crime, of which the party shall have been duly convicted.” That clause served as the legal basis for Alabama’s convict-labor system, used until 1928 to all arrest Black Alabamians, often on dubious pretexts, and force them into difficult and often deadly work. Three states — Colorado, Nebraska and Utah — have removed similar language from their constitutions since 2018.

- Strike language directing poll tax revenues to counties for educational purposes. Poll taxes disenfranchised Black Alabamians and poor whites. The 24th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1964, banned the practice. Most other poll tax provisions in the Alabama Constitution were removed by Amendment 579, Lathram said.

- Strike language from a 1956 amendment to the Constitution, passed in the wake of Brown vs. Board of Education, that would authorize the Legislature to allow children to “attend schools provided for their own race,” as well as a provision allowing the Legislature to intervene in schools in the name of “peace and order.” Supporters of segregation used the phrase in the 1950s. Alabama Attorney General John Patterson argued in August 1956 that the city of Montgomery could not maintain “peace and order … if, by court decree, a Negro man is permitted to sit by a white woman.”

Committee members did not raise objections to the plan. A formal vote on the proposal should take place within the next few weeks.

“I just want to make sure that we’re all on the same page, because at the end of the day, I want to say that this is a document that was bipartisan,” said Rep. Merika Coleman, D-Pleasant Grove, who chairs the committee and sponsored the 2020 constitutional amendment that led to its formation. “Really nonpartisan, because it shouldn’t be partisan at all.”

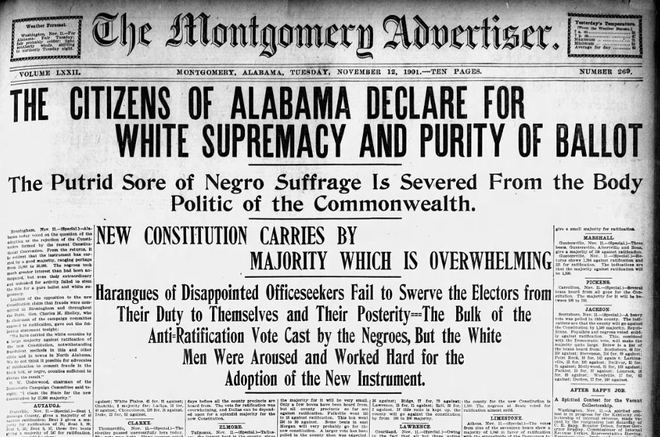

The framers of Alabama’s 1901 constitution — still the state’s governing document — designed it to disenfranchise Black Alabamians and poor whites, and waged a racist campaign to see it enacted.

More:The defeated: A brief history of Alabama’s first 200 years

“And what is it we want to do?” John Knox, the president of the convention, told the delegates to the convention in May 1901. “Why, it is within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this state.”

The constitutional amendment setting up the commission, sponsored by Coleman, had bipartisan support and got the approval of about two-thirds of Alabama voters in 2020.

Some committee members who supported the changes expressed concerns about the potential for future litigation. Stan Gregory, an attorney serving on the committee, said that if the mandate of the committee was to address racist language, addressing issues like the poll tax — which, on its face, was applied to all — could open a door to litigation.

“It’s not much,” said Gregory, who said he supported the removal of the poll tax language. “I think that it’s defensible. I just point that out — that’s something that worries me.”

Lathram said he understood the concern but said the applications of the provisions throughout state history were racist. He said h believed the proposal considered in its “totality” would withstand legal challenges.

The 1956 amendment asserts that there is not “any right to education or training at public expense.” That language would remain in the document under the plan.

The Legislature will take up the committee’s recommendations when they return in January, in the form of a constitutional amendment. If the amendment passes, it will go to voters in November 2022.

Federal laws and court rulings have nullified most of the racist provisions that remain within the state constitution. But Coleman said the changes would send a message.

“Our state constitution is reflective of who we are,” she said after the meeting. “Those racist provisions in that constitution, those outdated provisions — we hope that’s not who we are, and we definitely know we’re not a 1901 Alabama, and we need to reflect that in the document.”