How Europe’s Migration Policy Helps Human Traffickers

In 2015, Europe was hit with a tsunami of migrants. Over a million people landed in Europe that year, fleeing war, poverty or political oppression in Syria, Sudan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Eritrea, Ethiopia and more. European countries most affected – Greece and Italy in particular – scrambled to establish deals with gateway countries – Turkey and Libya – to stem the steady flow across the choppy and perilous Mediterranean and Aegean waters. The 2016 deal between the EU and Turkey and the subsequent 2017 agreement between Italy and Libya created financial incentives to gateway countries to keep refugees from crossing the water. EU and Italy invested in the Turkish and Libyan coast guards and contributed financially to the upkeep and management of their migrant camps.

By financially investing in a crackdown rather than in increasing the efficiency of legal, safe migration routes into Europe, European policy narrows refugees’ options and effectively herds them into the hands of traffickers. More galling is that these policies are often implemented in the name of stopping human smuggling and human trafficking – two concepts that are conveniently conflated.

The EU deal with Turkey made it more difficult to cross the Aegean Sea, and as a result, more refugees began to travel through Libya. The EU deal with Turkey is based on the “untrue, but willfully ignored, premise that Turkey is a safe country for refugees and asylum-seekers.” While human rights conditions for migrants are deplorable in Turkey, Libya is far far worse. In fact, migrants traveling via Libya are “between seven and 10 times more likely to be abused than those reaching Europe from Turkey.” A CNN investigation in November 2016 found evidence of openly operating slave markets where human beings – mostly from West Africa – were being sold for as little as $400. But the slave markets are only a final stop after a long journey of abuse and exploitation.

Migrants traveling by land to reach Libya are desperate. Economically motivated migrants mix with refugees who are fleeing war, political oppression, and torture. European funded detention centers in Turkey and Libya do not have well-functioning methods for distinguishing between refugees and other migrants. Regardless of the push factors, many migrants in Libya soon find themselves trapped in a vicious and dangerous cycle of exploitation and abuse – so even if the original aim was to escape poverty alone, many migrants in Libya are now trying to escape violence and need protection.

Let us imagine a typical migrant – Andrew (not his real name). Andrew’s harrowing story was documented by Yomi Kazeem for Quartz Africa in October 2018. According to Kazeem, Andrew decided to leave his home of Edo, Nigeria in search of a better life. Edo is a haven for traffickers, and though Andrew knew this, he decided to try his luck. He paid $1750 to a local agent to arrange his transport. $1000 was to cover his journey from Nigeria into Niger, across the Sahara desert, and into Libya. $750 was to cover his passage from Libya into Italy. At each stop, the smugglers would read out the names of people whose agents had passed along the full fee. Anyone whose agents had swindled them was beaten and tortured until they found a way to pay – usually through high ransoms sent via Western Union by concerned family members back home. Andrew was lucky – at each step of the way, it seemed his agent had paid the full fee – until he reached a migrant detention center in Libya. With the crackdown on sea crossings, passage to Italy had become riskier and therefore more substantially more expensive. There he was told he owed $2500. He had no money left – he had depleted all his savings on food and bribes to border officials along the way. He was beaten for ten days until his parents wired him the funds. He was lucky – his parents had the money and the means. Those who cannot pay are taken to the slave markets, or forced to pay through sexual favors.

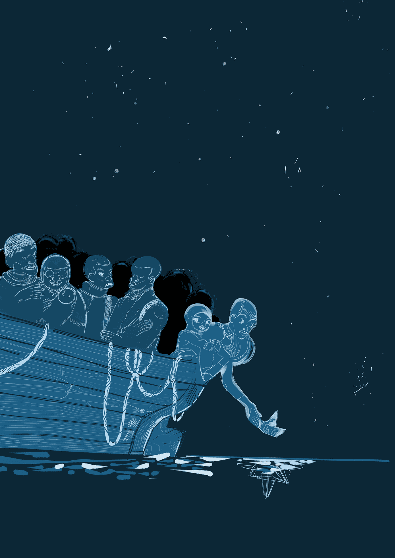

Andrew stayed on at the camp but relied on regular transfers from his parents – the smugglers deducting at times as much as a third of the transfers they sent. He waited and waited for a chance to cross to Italy. Now the Libyan coast guard – funded in large part by Italy, — were cracking down on the overcrowded rafts trying to reach Europe. Andrew tried one crossing and was turned back to the camp. More extortion, more bribes as he waited another six months for another chance to cross. Those who could not sustain the financial support from family back home were beaten then taken to the slave markets. Officials – often the same officials whose salaries were now being subsidized by Italy — were taking bribes. The camps – also funded in part by Italy – were distribution centers for slave markets. We know Andrew’s story because he was one of the lucky ones – he made it to Italy on an overcrowded raft that ultimately relied on the Italian coast guard for rescue. Now, he might not have been so lucky – the Italian government has recently refused to respond to rescue calls or to allow boats to disembark on Italian soil in an effort to dissuade crossing attempts.

In 2015, smuggling migrants into Europe generated an estimated $7 billion. Human smuggling — and within that the subset of human trafficking – has become a parallel economy. Although there has been a significant decrease in migrants reaching Europe in recent years, these economies continue to flourish. In fact, the money invested by Europe to prevent migrants from landing on its shores essentially subsidizes and boosts human smuggling profits. The more complex the border crossing, the more sophisticated the help that is needed. The more involved and risky the assistance, the more expensive it is, leading to an increase in fees, leading to more pay-later schemes – creating optimal conditions for human trafficking. The Italian-funded Libyan coast guard crackdown means fewer boats are making it across the water, which leads to a backlog of migrants in Libya. The fewer migrants who make it into Europe, the more who are trapped in insecure conditions, the more who are sold into slavery.

Image Source: “Le Barche sono come i corpi” by Kanjano – is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0