It is a new day in Conakry, the capital city of Guinea, and the port is buzzing with activity. At the break of dawn, a lone figure can be seen with a fishing net. The fisherman, identified as Keita, toils for long hours, and at the end of the day, he sits dejected with his catch. He soliloquises, reminiscing when his business flourished and he could handle his basic needs.

Mohammed Soumah, another artisanal fisherman at the Bonfi landing stage, also faces the same predicament. Both men struggle to make ends meet due to the declining fish stock partly caused by the damaging effects of illegal fishing.

The Gulf of Guinea, where these fishermen operate, is a significant location for fishing and shipping. Guinea’s port is critical in transporting oil, gas, and goods to central and southern Africa. However, the illegal fishing practices of local and foreign vessels operating without proper authorisation jeopardise the livelihoods of artisanal fishermen like Keita and Mohammed. The fishermen are now victims of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU).

“It hampers our efforts and disrupts our natural fishing environment. Our fish stock is depleting, and we no longer see some types of fish,” Mohammed lamented.

Illegal fishing, which refers to unauthorised and unregulated fishing activities, poses a significant threat to marine ecosystems worldwide. Alongside unreported fishing, where unidentified vessels engage in fishing activities, these practices violate the conservation of aquatic life and undermine governance efforts to protect marine resources. Unfortunately, like many other countries, Guinea has fallen victim to these crimes.

Government response

In response to this challenge, the government of Guinea has forged partnerships and collaborations with regional task forces to combat illegal fishing. For instance, the Ministry of Fishery and Marine Economy has joined forces with international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), including Ocean 5 and the World Partnership for Environmental and Marine Specialists, comprising GRID-Arendal, TMT, and PRCM. These partnerships aim to enhance the capacity of stakeholders, particularly those in the fisheries sector, to address the issue of illegal fishing.

The African Union and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) have also established regional think tanks, promoted cooperation among their navies and maritime agencies, and facilitated information sharing and training. These collaborative efforts are crucial in curbing illegal fishing and safeguarding marine ecosystems for present and future generations.

Nasir Saheed (not real name), an expert on maritime, security, and governance and member of the regional cooperation body in charge of monitoring and protecting the Gulf of Guinea, said, “IUU is one of the maritime crimes that affect the development of the blue economy potentials to benefit national prosperity across nations, states across the Gulf of Guinea from Senegal to Angola and even beyond. IUU ties into food security concerns of those committing the crime and the victims of crime that have to contend with the devastating effect of the crime in the Gulf with the increased reports from coastal communities on the diminished fish catch, and this affects other economic activities even that of meeting their basic needs.”

The European Union has also expressed deep concern about the threat posed by transnational crimes such as piracy, armed robbery, drug trafficking, and human and migrant trafficking at sea in the Gulf of Guinea.

Ship loitering

Guinea’s coastal fringe and large continental shelf contains dense river systems that provide abundant water resources. Unfortunately, the local population has yet to tap into these resources fully, and foreign nations often exploit them. These foreign vessels can be seen wandering around the shores of Guinea, exhibiting a behaviour known as “ship loitering.”

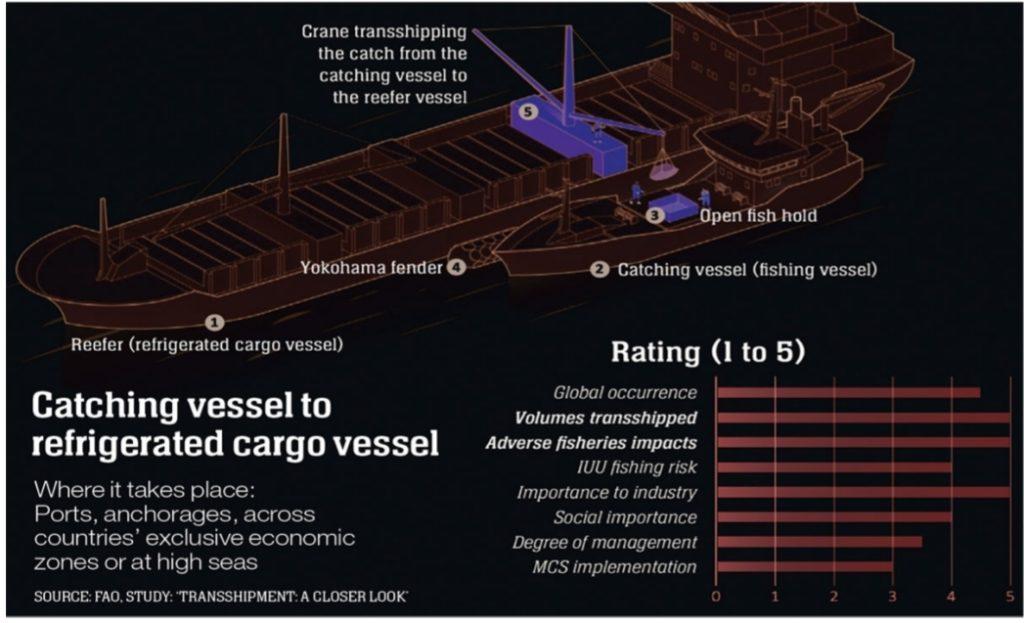

Ship loitering refers to a vessel’s frequent turning within a specific area, which indicates a potential encounter event. This behaviour is commonly observed at ports, anchorages, and in countries’ economic zones, as well as on the high seas. In most cases, transhipping is involved when loitering occurs. However, exceptions exist where a vessel may remain relatively steady, such as during maintenance or waiting for permission to dock outside a port.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), transshipment is the transfer of catch from one fishing vessel to another or a vessel used solely for cargo carriage. At sea, transshipment has been linked to IUU fishing and the facilitation of criminal activities.

Transferring fish caught from small fishing boats to larger refrigerated carriers or “reefers” may seem innocuous. Still, when left unmonitored and unregulated, it can contribute to biodiversity loss, overfishing, seafood fraud, and human rights violations such as forced labour, human trafficking, migration, and piracy.

One of the effects of IUU is human trafficking, which involves the exchange of humans as commodities. The Global Estimates of Modern Slavery 2022 report by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) notes that IUU fishing significantly contributes to forced labour risks, with an estimated 128,000 fishers trapped in forced labour aboard fishing vessels, often at deep sea.

In Guinea, human trafficking is a serious concern, with adults and children being forcibly taken away from their homes and loved ones. For example, the Center on Human Trafficking Research and Outreach reports that many children in Boké and Mamou are estimated to have experienced trafficking, with some incidents reported in the fishing sector.

Springboard for transnational crimes

Maritime experts have identified IUU fishing as a springboard for transnational crimes, including human trafficking. Guinean fishermen have reported close encounters with foreign ships reportedly engaging in human trafficking, arms trafficking, and drug trafficking. In one instance, fishermen narrowly escaped death after being allegedly fired at by a foreign boat, and investigations into the incident remain unresolved.

The impact of IUU fishing goes beyond human trafficking and includes biodiversity loss, overfishing, seafood fraud, and other crimes. Guinea’s fishermen are severely affected by IUU fishing and call on the Guinean authorities to take action to protect them and their livelihoods.

“If a vessel is already fishing illegally, it would also be open to serve as a platform to move illicit substances because it has come up as a criminal vessel fishing without papers or authorisation using cost-benefit analysis. As a criminal, they would reason why don’t they just add some other “venture” to it like drugs, and because they are already involved in other criminal enterprises, they would not find it hard or wrong to keep people against their will, and moving people from one part of the world to another” Saheed added.

Abdulganiyu Abubakar, the regional representative of the West Africa Coalition Against Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants (WACTIPSOM), has stated that Guinea is a significant source, transit, and destination country for human trafficking and other transnational crimes, including cybercrime, labour exploitation, and other forms of exploitation. He notes that these activities often go unnoticed and undetected.

Syndicate groups are also involved in human trafficking, with some Guinean nationals accused of collaborating with individuals from countries such as Senegal and The Gambia. This triad exploits men, women, and children across West Africa.

The 2022 Trafficking in Persons Report lists Guinea as a transit country for West African children subjected to forced labour in artisanal gold mining across the region. The report also notes that girls from West African countries migrate to Guinea, where traffickers exploit them in domestic service, street vending, and to a lesser extent, sex trafficking. In general, human trafficking has a detrimental effect on regional security, with external actors frequently enlisting the aid of local agents to serve as their proxies.

The US Department of State’s 2022 Trafficking in Persons Report states that the government of Guinea established the Comité National de Lutte Contre la Traite des Personnes et des Pratiques Assimilées (CNLTPPA) to combat human trafficking. The government allocated resources to the CNLTPPA, which set up a hotline for reporting trafficking cases and developed a national action plan to address this crime.

The CNLTPPA has been collaborating with NGOs, who reported an additional 128 forced labour trafficking victims, including 20 children.

One reason these incidents have gone largely unreported is the political situation in Guinea. The country has experienced numerous governance and power transitions. Following the military takeover, there has been a significant amount of repression and dictatorship, including a crackdown on journalists and media. While civil society organisations and pressure groups exist, they are in their infancy, unlike in other West African countries with a stronger presence.

Including human trafficking in the context of IUU fishing adds another dimension to the problems and challenges faced in Guinean waters. It overburdens the already stretched enforcement agencies that deal with these crimes that underscore the need for the government to prioritise its responsibility to protect life and property. It involves acknowledging the existence of criminal elements and promising to intensify awareness campaigns and support security agencies in combating these vices.

The role of law in combating IUU and its effects

IUU fishing and human trafficking pose a significant threat to Guinea’s marine ecosystems, resulting in annual revenue loss for the government. To combat these crimes, there should be intensified efforts to investigate, prosecute, and convict suspected traffickers and officials who collude with them. However, the government faces constraints in the form of limited finances, expertise, and technical know-how in the maritime industry. Therefore, collaboration and partnerships with relevant stakeholders should be considered.

To deter these crimes, the penal code should be amended to impose the strictest punishment appropriate for the offences committed. Sentencing provisions that allow fines instead of imprisonment should be removed, and punishments should be commensurate with other serious crimes. This would act as a deterrent and help prevent the continued revenue loss from these illegal activities.

Efforts to identify trafficking victims among vulnerable populations should also be increased. NGOs should receive more funding and in-kind support to ensure that identified trafficking victims receive the necessary services. On the other hand, law enforcement and service providers should be trained on standard procedures to identify and refer trafficking victims to appropriate services. This would not only provide victims with the necessary support but would also aid in preventing future incidents.

Extradition agreements with African and Middle Eastern countries should be developed and implemented to ensure that traffickers are brought to justice. This would prevent them from evading punishment by fleeing to other countries.

Moving ahead, it is essential for all agencies involved to collaborate in identifying the underlying causes of UUI fishing and implement measures to combat this criminal activity. However, it is equally important to prioritise the welfare of those affected by these illicit practices. By working together and keeping the best interests of all stakeholders in mind, the challenge can effectively address the issue and create a more sustainable and equitable future.

This story was supported by Code for Africa (CfA) in partnership with GRID-Arendal as part of the Environmental Journalism fellowship on IUU fishing in Guinea.