Sex Trafficking: Don’t Neglect the Victims

Media attention to sex trafficking has a predictable ebb and flow. As it played out recently in a high-profile case in Florida, it starts with police stings, arrests and recovered victims. Then we recoil as we learn who was arrested, which in the Florida case, included two Disney employees, a state corrections officer, a state police officer and several school teachers.

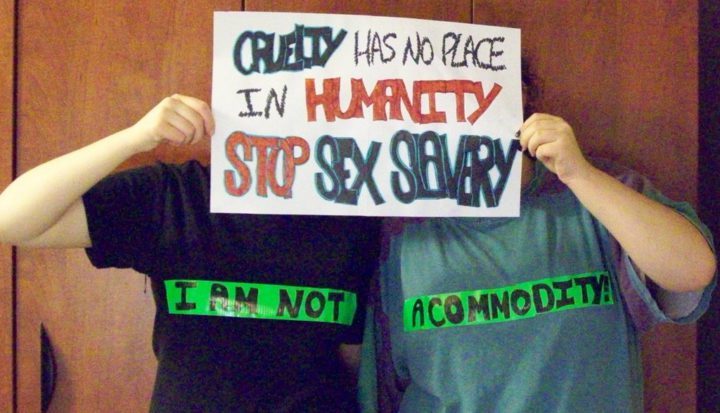

We feel sympathy for the victims. But sympathy is expressed in different ways. Some argue that we wouldn’t have this problem in society if sex work were decriminalized, or if we weren’t sexually immoral, or if we cared more about children, or sexual minorities, or women, or God.

And then we collectively move on, neglecting the fact that recovered victims often cannot.

Sex trafficking occurs when a person is misled, forced, or coerced to exchange a sex act for money or goods, or when the person exchanging the sex act is under the age of 18.

While anyone can be trafficked for sex, victims are disproportionately young, female, or members of racial and sexual minority groups. They have often experienced multiple forms of violence and trauma prior to their sex trafficking victimization.

While focused on survival, they may have missed out on important life course milestones like obtaining a high school diploma or college degree, securing conventional employment, building relationships with safe people, and saving up money for an apartment deposit or a down payment on a car.

Some are offered a window to leave their traffickers, but leaving is not so simple.

With no money, housing, transportation, education, employment history, or social support from people outside “the life,” there may be nowhere else to turn.

This is why sex trafficking researchers have found that victims are rarely able to exit on their first attempt, but will often return to their traffickers multiple times before they are able to cut ties for good.

When I worked with sex trafficking survivors as a social worker, I witnessed these barriers firsthand.

The barriers twisted into a kind of Gordian knot that could feel unsolvable, insurmountable.

One young woman I worked with shared a common story: She’d run away from an abusive home as a teenager, ended up on the streets, was tricked into exchanging sex for a place to stay, and quickly became pregnant by her trafficker.

By the time she came to me, it would have taken several years and significant financial resources for her to establish stability—and only if everything went right. It didn’t, though. Her car was repossessed, she lost parental rights to her child, and I didn’t see her again.

This woman’s story haunted me.

Even though I was her case manager, and I worked for an agency specifically focused on sex trafficking survivors, I did not have access to the quantity and type of resources that she needed to forge a way out.

My advocacy efforts and my agency’s program had failed her. I wanted to better understand why.

A few years ago, a colleague and I sat down to discuss barriers to sex trafficking exit with seven women who had survived and successfully made it out. We wanted to understand how these women had coped, and the types of services they had encountered during their exiting process.

Each of these women now work as anti-trafficking advocates, so they had both personal and professional experience to share with us for our research study.

In these conversations, it became even more clear to me that meaningful victim recovery cannot just include law enforcement stings and referrals to short-term victim services, even though this is what society seems to emphasize.

Indeed, the women we talked to stated that the sheer number and type of barriers that they faced means that services must be trauma-informed, long-term and comprehensive.

While different models for this type of care exist, the effective ones are likely to share some common features. First, they offer programs that can quickly link survivors to case management, counseling, crisis intervention services, shelter, and medical assistance.

Second, these types of programs are offered in-house, so that survivors are not given a runaround when trying to access services in multiple locations.

Third, effective programs have a plan for how to provide services to incarcerated victims, immigrants and refugees, and tribal victims, as these subpopulations are often overlooked.

“We just don’t have the right programs,” One survivor explained. “Don’t they need to be long-term?

“They need to be 18-month to three-year programs. We need to be able to give and meet all of their needs for that basic part first, because otherwise they’re going to [return] back.”

Other survivors echoed her sentiments. They stated that meaningful anti-trafficking programs must be fully funded and comprehensive enough to provide survivors with necessary care to promote their full recovery.

Many anti-trafficking programs just aren’t equipped to provide what survivors need most.

Mary Twis

If we truly care about sex trafficking and want to see it stop, we must understand that caring for survivors does not and cannot end with law enforcement and crisis intervention services.

We must provide enough resources – time, funding and professionalization of services – to ensure that survivors are effectively cared for.

Mary Twis is an assistant professor of social work at Texas Christian University who specializes in research on human trafficking.