It was an offer he could not resist: an easy job overseas, a sizeable salary, and even a chance to live in a swanky hotel with his own personal trainer.

When Yang Weibin saw the ad for a telesales role in Cambodia, he immediately said yes. The 35-year-old Taiwanese wasn’t making much as a masseur, and he needed to support his parents after his dad suffered a stroke.

Weeks later, Weibin hopped on a plane to Phnom Penh. When he reached the Cambodian capital, he was met by several men who drove him to a nondescript building on a deserted road – not quite the luxury hotel shown in pictures sent by the recruitment agent.

His passport was taken from him – to sort out his paperwork, he was told. He was shown to a small bare room – his new home. And one more thing, the men said: you can’t leave the compound, ever.

The penny dropped. “I knew then I had come to the wrong place, that this was a very dangerous situation,” he told the BBC.

Weibin is among thousands of workers who in recent months have fallen prey to human traffickers running job scams in South East Asia. Governments across a vast swathe of Asia – including Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Taiwan – have sounded the alarm.

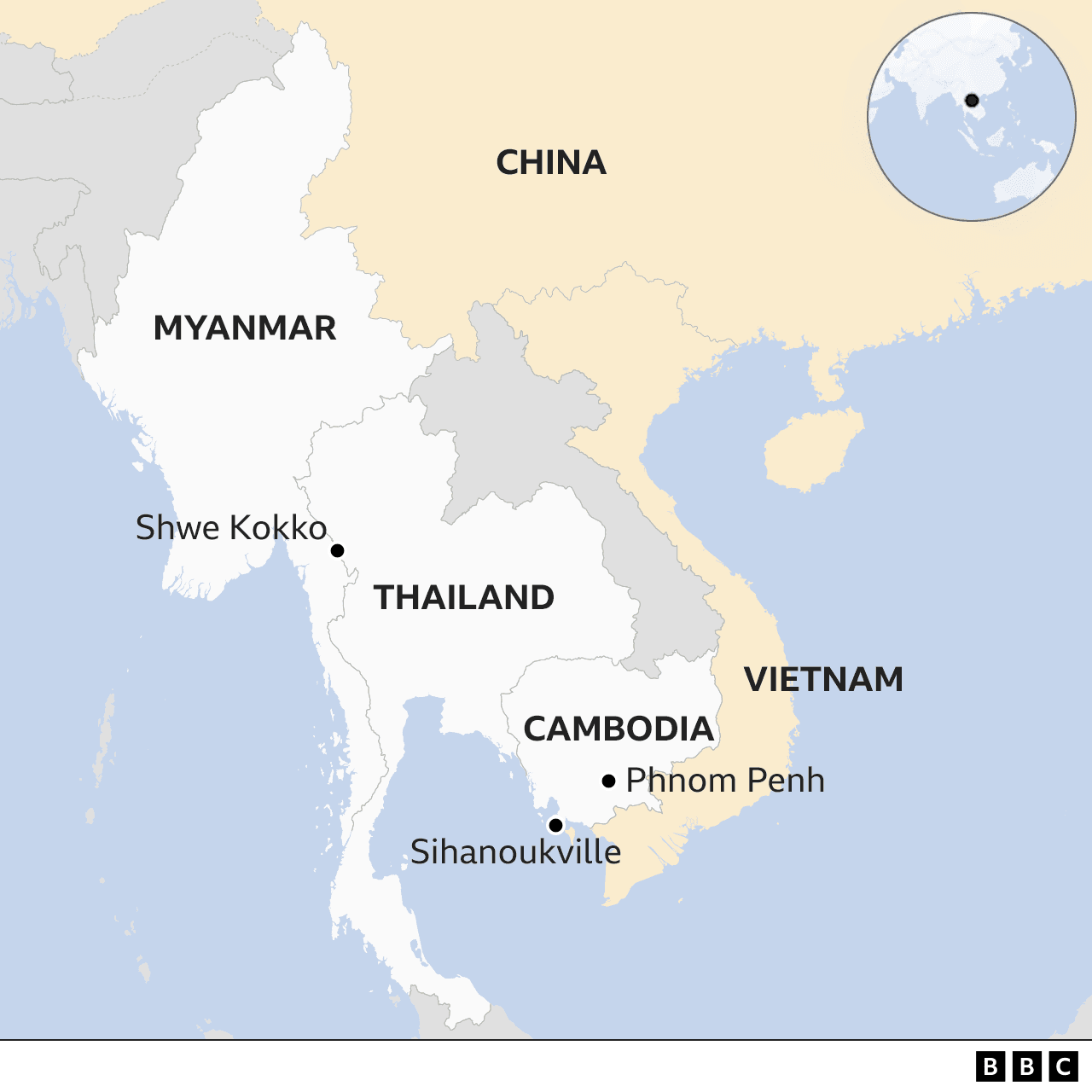

Lured by ads promising easy work and extravagant perks, many are tricked into travelling to Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand. Once they arrive, they are held prisoner and forced to work in online scam centres known as “fraud factories”.

Human trafficking has long been an endemic problem in South East Asia. But experts say criminal networks are now looking further afield and preying on a different type of victim.

Their targets tend to be quite young – many are teenagers. They are also better-educated, computer-literate, and usually speak more than one regional language.

These are seen as key by traffickers who need skilled labour to conduct online criminal activity, ranging from love scams known as “pig butchering” and crypto fraud, to money laundering and illegal gambling.

Chi Tin from Vietnam told the BBC he had to pose as a woman and befriend strangers online.

“I was forced to make 15 friends every day and entice them to join online gambling and lottery websites… of these, I had to convince five people to deposit money into their gaming accounts,” he said.

“The manager told me to work obediently, not to try to escape or resist or I will be taken to the torture room… Many others told me if they did not meet the target, they would be starved and beaten.”

The abuse often results in lasting trauma. Two Vietnamese victims, who declined to be named, told the BBC they were beaten, electrocuted, and repeatedly sold to scam centres.

One of them is just 15 years old. Her face disfigured by the abuse, she has dropped out of school since returning home, ashamed to face her friends.

The other, a 25 year old man, shared this picture taken by one of his captors which was used to demand a ransom from his family. It shows him handcuffed to a metal bedframe with visible bruises on one knee where he was electrocuted.

The victims are told to pay off “debts” they owe to the scam centres if they want to leave – essentially a hefty ransom – or risk being sold to another scam centre. In Chi Tin’s case, his family managed to scrape together $2,600 (£1,600) to buy his freedom.

Those who can’t afford it have little choice but to attempt a perilous escape.

In one highly publicised case last month, more than 40 Vietnamese imprisoned in a Cambodian casino broke out of their compound and jumped into a river in an attempt to swim across the border. A 16-year-old died when he was swept away by the currents.

While Cambodia has emerged as a major hotspot for the scam centres, many have also popped up in border towns in Thailand and Myanmar. Most of them appear to be Chinese-owned or linked to Chinese entities, according to reports.

These companies are often cover for Chinese criminal syndicates, said rescue and advocacy group Global Anti-Scam Organization (Gaso).

“Many are quite sophisticated with separate departments for IT, finance, money laundering for example. The bigger ones can be corporate-like, with training provided for scamming, progress reports, quotas and sales targets,” said Gaso spokesman Jan Santiago.

They’re also multinational outfits, as the syndicates often partner local gangs to run their scam centres or do recruitment. Last month, Taiwanese authorities said more than 40 local organised crime groups were involved with South East Asian human trafficking operations.

While Chinese-run telecom and online scams have long been a problem, Covid changed everything, say experts.

Criminal networks figured out how to quickly pivot to online operations during the pandemic. Many of the traffickers also used to target Chinese workers, but China’s strict travel restrictions and multiple lockdowns have cut off this major source of labour, prompting traffickers to turn to other countries.

This has coincided with a surge in jobseekers in Asia as the region emerges from the pandemic with battered economies.

“A lot of the victims are young, some have graduated from universities and have limited job opportunities. They are seeing these online promises of decent jobs and following them,” said Peppi Kiviniemi-Siddiq, a specialist in Asia-Pacific migrant protection with the UN’s International Organization for Migration.

With many Asian countries relaxing Covid travel restrictions in recent months, she added, human traffickers have found it easier to lure and move people around, “operating with impunity in states with less capacity to tackle organised crime”.

Another factor is increased Chinese investment in the region, mostly through the Belt and Road Initiative, which has improved connectivity – but also the ability for organised crime to expand their reach, say experts.

Last month, Thai authorities arrested She Zhijiang, a Chinese businessman with investments across South East Asia, including a billion-dollar casino and tourism complex in Myanmar called Shwe Kokko.

He was wanted by Interpol, which described him as the head of a criminal gang that ran illegal gambling operations in the region. Multiple victims have alleged they were trafficked, imprisoned and brutalised in Mr She’s complex, known by its nickname “KK Park”.

Law enforcement is only now starting to catch up. Cambodian police in recent months have worked with Indonesian, Thai, Malaysian and Vietnamese authorities to conduct rescues and crackdowns on scam centres, and have set up a direct hotline for victims.

Cambodia’s interior minister acknowledged it was a widespread problem, calling it “a new crime that has emerged brutally” – while also insisting it is overwhelmingly perpetrated by foreigners.

But victims and non-governmental organisations say Cambodian police, judges, and other officials are complicit, by colluding with traffickers or accepting bribes in return for dropping charges, according to this year’s US State Department report on human trafficking.

It notes that despite “consistent credible accusations”, many of these officials have not been prosecuted.

Ms Kiviniemi-Siddiq said much more needs to be done to fully stamp out the problem: “Some of these governments need to update their trafficking laws, have necessary support systems for individuals, and more transboundary law enforcement cooperation – which is hard to achieve and takes time.”

In the meantime many countries have launched public education campaigns to raise awareness of the scams.

Some have introduced screening for people leaving for South East Asian destinations, for example by stationing police at airports to ask people about their reasons for travel. Last month, Indonesian officials stopped multiple private flights chartered to ferry hundreds of workers to Cambodia’s Sihanoukville.

Groups of volunteers helping victims escape and return home, such as Gaso, have also sprung up in several countries. Some of these volunteers are former victims themselves – like Weibin.

After spending 58 days in captivity in Cambodia, he managed to escape one morning by crawling out of the compound while the guards weren’t looking. With the help of anti-scam activists, he finally returned home and is now back at his old job.

But his massage stall has a new feature: a large white sign with a handwritten account of his experience in Cambodia. He’s also shared his story extensively online and in Taiwanese media.

“A lot of people really covet a good life and have unrealistic fantasies [about jobs]. Now I advise people to be more realistic,” he told the BBC.

“You can earn money anywhere. You don’t need to go abroad to take such risks. Overseas there are a lot of unknowns, it can damage your life in ways you can’t even imagine.”