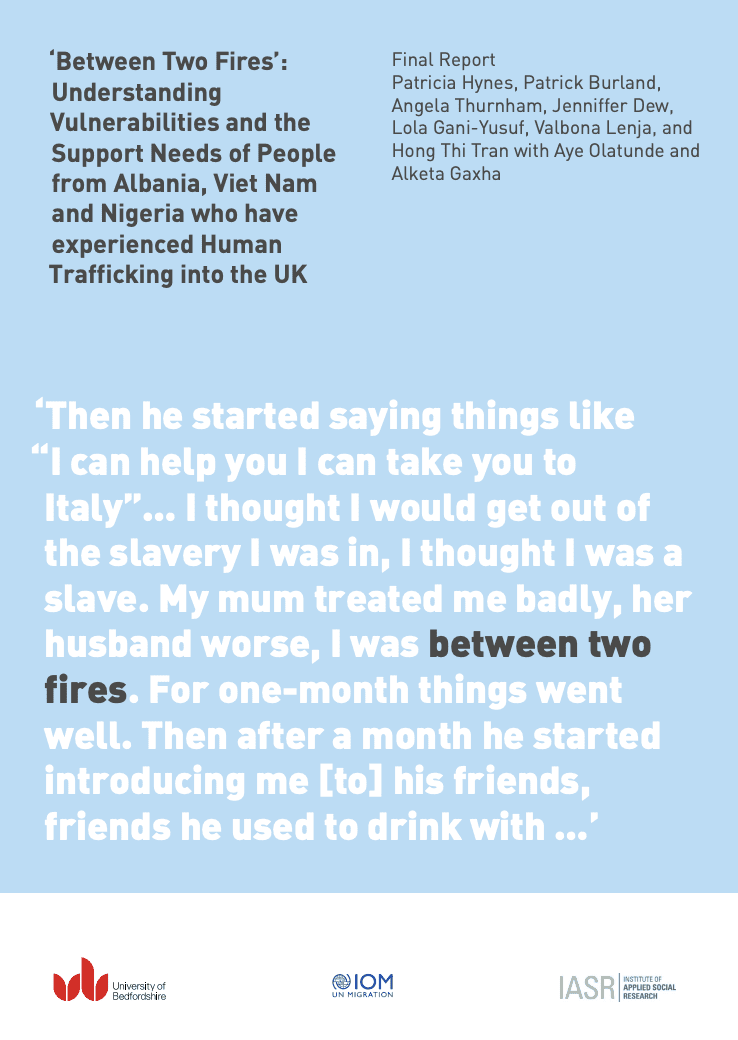

‘Between Two Fires’: Understanding Vulnerabilities and Support Needs of People from Albania, Viet Nam and Nigeria who were Trafficked to the UK

Executive Summary:

This is a report of a two-year research study into understanding the causes, dynamics and ‘vulnerabilities’ to human trafficking in three source countries – Albania, Viet Nam and Nigeria – plus the support needs of people from these countries who have experienced trafficking and are now in the UK. The report focuses on these countries because they have consistently been among the top countries of origin for potential trafficked persons referred into the UK’s National Referral Mechanism (NRM). The study was carried out as a partnership between the University of Bedfordshire and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

AIMS OF THE RESEARCH STUDY

1. Explore socio-economic and political conditions plus other contextual factors that create ‘vulnerability’ to, and ‘capacity’ against, human trafficking in Albania, Viet Nam and Nigeria

2. Utilise and refine IOM’s Determinants of Migrant Vulnerability (DoMV) model

3. Outline routes taken from Albania, Viet Nam and Nigeria to the UK

4. Review existing academic and ‘grey’ literature on trafficking within and from Albania, Viet Nam and Nigeria

5. Explore the support needs of people who have experienced trafficking from Albania, Viet Nam and Nigeria and have arrived into the UK, plus highlight examples of good practice in human trafficking work across these countries

RESEARCH APPROACH This study is qualitative in its approach and follows country-specific Shared Learning Event reports about Albania, Viet Nam and Nigeria. A total of 164 semi-structured interviews with adults who had experienced human trafficking (n=68) and key informants (n=96) with knowledge about human trafficking were conducted in Albania, Viet Nam, Nigeria and the UK. Data collection took place between and February and November 2018.

The voices of those who have been directly affected by human trafficking are still largely absent from research in this area. In this report the personal testimony of trafficked persons is used to understand vulnerabilities to trafficking and the routes and journeys of people trafficked from Albania, Viet Nam and Nigeria to the UK. The report also captures the reflections of trafficked persons on their support needs and practices, plus what could be done to improve such work in the future.

This research uses an IOM DoMV model as a framework for analysing vulnerabilities to trafficking. This is a model to address the protection and assistance needs of migrants who have experienced or are vulnerable to violence, abuse, exploitation or rights violations before, during and after migration. The model includes four levels – individual, household and family, community and structural levels – to facilitate more comprehensive understanding of vulnerabilities during migration.

KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS:

The key findings are highlighted below. Each one is followed by recommendations as to how it could be addressed.

1. Vulnerability to trafficking is influenced by a constellation of overlapping and interconnected risk factors which cut across individual, household and family, community and structural levels and vary from country to country. Individual level factors were most often discussed by respondents, however these are firmly embedded within broader family, community and structural factors that can create enabling environments for trafficking. Respondents provided detailed contextual descriptions of factors at the household and family level which appear to be particularly significant in the lives of people who have been trafficked. These include households affected by specific social issues (such as gender discrimination, domestic abuse, substance abuse, physical and sexual violence), or households in which there are pressures to migrate, particularly in the context of sudden shocks, such as the death of a family member. En-route, and in destination locations, vulnerabilities rapidly change and are influenced by factors such as the journeys people take, their levels of isolation and/or or ability to access help, the nature of their exploitation and their dependency on people who exploit them.

- Implement multi-faceted responses to address vulnerabilities at all levels. These should be based on an analysis of the most significant risk factors, which should have a broader focus than the individuals alone, incorporating family, community and structural considerations, and an understanding of which of these factors can be meaningfully addressed or changed.

- Complement the DoMV model as a framework to understand vulnerability factors with a political economy analysis in locations of origin of victims to understand the influence of historical, political, economic and structural factors which may be more complex and systemic (e.g. legislation, policy and governance issues) and not fully described by victims of trafficking or key informants. Ensure that the role of peers and social networks are fully analysed at the household and community levels.

- Enhance protection activities associated with the home, family and intrafamilial environments. This could include whole-of-family approaches to improve intra-household gender relations, responses to maltreatment, abuse and violence against women and children, which focus on family members working together to improve relations and decision-making. These interventions should be coupled with improvements and enhanced access to social care provision for families to promote the well-being of vulnerable children and adults.

2. Harmful social norms and practices exist and intersect with human trafficking, often in a gender-specific way. Such harmful norms and practices were most often discussed in Albania and Nigeria within household and community settings, and included examples of conservative gender norms, such as early and forced marriage or limited access to education or livelihood opportunities for women and girls. In these circumstances, women and girls may seek to avoid or resist these vulnerabilities by seeking opportunities to leave their household or community settings, increasing the risk of accepting offers from people offering to facilitate this process.

- Conduct in depth analysis of community and social contexts in which trafficking is known to take place to understand the influence of social norms.

- Explore intervention opportunities to challenge traditional attitudes about gender and violence against women and girls with both men and women, building on learning from other sectors focused on these issues. In Nigeria, this may include training of faith and community leaders to speak out and make these practices less socially acceptable.

3. Limited financial, educational, employment or healthcare services within a community can create a mismatch between an individual or family’s opportunities and aspirations to improve their standard of living and socioeconomic status. People feeling constrained by their circumstances or perceived limited opportunities in their community settings was raised by key informants as a risk factor within a community setting which can create or exacerbate socio-economic challenges at the individual and household and family levels. Across all countries, there appeared to be a mismatch between hope and aspiration which can influence decisions to migrate. In Viet Nam an individual’s view about their role in providing for the family and perceived rewards from work abroad, meant individuals (most of whom were men) sought out or accepted offers of well-paid employment to economically provide for family members, often accepting risks of hardship in the short term. In Nigeria, prioritising educational opportunities for children overseas was a feature in family decision-making, with offers accepted from people who claim to be able to facilitate this.

- Strengthen health, education or community services and enhance access for all community members, including those who may be not be being reached by the current provision, especially in settings outside of the large cities.

- Link, enhance or partner with existing livelihood programmes being implemented by government or non-government actors, or identify locations that are not adequately covered.

- Explore community-based methodologies that focus on enabling communities to identify and mobilise existing, but sometimes unrecognised, assets and strengths.

- Explore the potential of expanding productive employment opportunities for men and women through labour migration programmes.

4. Journeys often begin with rational decision-making which is based on limited or unreliable information about costs, length, dangers, legal requirements, alternatives, or situation en route and at destination. Once journeys begin, they can become progressively precarious with individuals facing new and rapidly changing vulnerabilities. These include violence, extortion, abuse, exploitation, lack of food or water and social exclusion, and sometimes death. Risk and harm tend to increase over time while capacities to mitigate or resist them reduces, as people become increasingly dependent on others that can cause them harm, when communication and access to support is limited and debts increase. In this study, journeys from Viet Nam were found to be particularly dangerous, with widespread violence, abuse and exploitation in multiple locations and over an extended period of time, while journeys from Albania to the UK often involved exploitation in another European country before coming to the UK.

- Enhance protection at key stages of a journey with interventions that are based on contextual realities about the ways people are being exploited, the most critical points and places to intervene, and the best mode of delivery. This could include information and resource centres which provide support and assistance to vulnerable migrants. The DoMV can help identify the vulnerabilities at play if used at different stages in a journey.

- Consider the most appropriate ways to engage with the relevant diaspora communities in these locations to strengthen their capacity to offer protection and reduce their potential for harm, particularly on routes from Viet Nam to the UK.

5. Cultural and religious beliefs about how luck and divine power can provide protection appear to influence attitudes towards risk and willingness to embark on journeys. In Viet Nam, ideas of luck and destiny appear to supersede what people may know about the dangers they could face on a journey or the potential for ‘failed migration’. In some cases, approaches to risk were influenced by perceived short-term hardship for long-term rewards in improved opportunities and stability. In Nigeria, faith in God was described as a factor that provides people with a sense of safety even when they may be aware of potential dangers. Some key informants in Nigeria described how pastors may contribute to this perception by giving blessings for people who are going to travel to Europe. Key informants in Nigeria also described the role of oath-taking and ritual in keeping people in exploitative situations.

- Conduct further research on attitudes towards risk and how these can influence behaviour related to migration and seek to identify opportunities for intervention.

- Work with religious leaders in Nigeria to raise their awareness of the level of risk people are exposed to on journeys to Europe.

- Explore the impact of the cultural/religious interventions such as those that have taken place in Nigeria in which oaths made by victims of human trafficking are publicly revoked.

6. Stigma can be both a driver and an outcome of trafficking and exploitation. For example, moral and conservative codes for women around divorce, pregnancy out of marriage, early marriage, the shame and stigma of domestic violence and in some instances shameful employment such as sex work can leave people isolated and vulnerable. In Viet Nam, stigma towards people who have debts or who are perceived to have failed in their migration aims can lead to discrimination within community settings. Similarly, the fear of suffering stigma and discrimination from their community and even their own families for the experiences suffered during their exploitation could also be used as a means of coercion, keeping them in a trafficking situation, or impacting on their opportunities for recovery post-exploitation when people are marginalised on the basis of their experiences they have faced.

- Develop interventions that seek to address stigma in household and community settings. This can involve work with faith and community leaders, as well as institutions responsible for the provision of social care, law enforcement and justice, in the form of capacity building and training.

- Engage and build the capacity of media to help ensure that reporting of issues of trafficking or wider social problems do not reify discriminatory messages in respect of gender norms, gender-based violence or child sexual violence.

7. There were mixed views from survivors about the effectiveness of awareness raising efforts to prevent trafficking. Some survivors described how they thought it was important for awareness raising around the dangers of human trafficking to try and prevent people from being affected in the future. However, other survivors were keenly aware of the limitations and appropriateness of such awareness raising approaches, considered against the strength and importance of beliefs and practices in determining their choices, or in the absence of credible alternatives. Among key informants, awareness raising featured heavily in discussions around prevention although its effectiveness was rarely discussed, evaluated or clearly understood.

- Carry out formative assessments, before implementation, in the specific locations in which awareness raising interventions are being considered to understand the likelihood of such messages being viewed as meaningful or credible by the target population and the most appropriate mode of delivery. In some locations, peer-topeer models may be more appropriate, while in others, family based approaches could be more effective.

- Evaluate existing awareness interventions for impact on behaviour, ensuring that these are not limited to a focus on the number of people reached or knowledge gained.

8. Some Vietnamese nationals are not being identified as victims of trafficking within the UK’s criminal justice and immigration enforcement systems. Testimonies of Vietnamese nationals who had returned home directly from UK prisons or immigration removal centres to Viet Nam and who were interviewed for this study, contained indicators of trafficking which did not appear to have been detected or acted upon while they were in the UK. Instead, individuals had often been treated as criminals or immigration offenders.

- Strengthen detection and screening processes in the UK’s criminal justice and immigration enforcement systems to ensure that potential victims of trafficking that have been engaged in forced criminality and/or have an unresolved immigration status are identified and can be protected not punished. This could involve training and awareness raising for frontline workers within these agencies on indicators of trafficking and exploitation as well as how to overcome barriers to disclosure. In addition, improve awareness of Section 45 of the Modern Slavery Act among key actors in the criminal justice system, including the Crown Prosecution Service, solicitors and Judges to ensure the non-punishment of those who have been identified as victims of trafficking.

- Engage with Vietnamese experts or community based organisations to understand what role they could play in this process, such as the provision of culturally specific informationwith this process to provide culturally specific information to relevant government agencies and to help them spot the signs of trafficking and encourage victims to disclose their experiences of exploitation.

9. Key informants and trafficked persons in the UK stressed the negative impact of the waiting time of the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) and asylum system upon the wellbeing and recovery of trafficked persons. The uncertain nature of awaiting decisions leaves people feeling that they have no control over their lives which was reported as having negative psychological repercussions. The waiting time and perceptions that individuals may have their accounts disbelieved or mistrusted contributed to limited confidence in the UK’s identification and determination processes among survivors and key informants, and can hamper the ability for support staff to build trust with survivors and 12 provide appropriate care. The government is seeking to address these concerns through the NRM reforms1 but at the time the study was being completed, these had not yet come into effect so their impact is unknown.

- Review the impact of NRM reforms once they come into full effect to ensure they are achieving their aims of achieving quicker decision making and that good quality decisions are building confidence among stakeholders and victims. Government has committed to evaluate its programme of NRM reforms and thier impact on timeliness and quality of the identification of victims of modern slavery. Work is currently underway to ensure there is robust evaluation of each strand of NRM reform activity.

- Explore the provision of culturally specific information and training to NRM decision makers to ensure they are aware of details about how victims from certain locations might present as well as country or location specific trafficking trends and cultural norms.

10. In the UK some of the committed and dedicated organisations carrying out a range of support services for victims of trafficking are operating outside of the NRM2 without government funding. This includes the vital work of country specific communitybased organisations who are providing culturally informed care to people in their own language. These organisations are providing informal care services and often supporting victims to understand the processes they navigate in the context of receiving care and support in the UK.

- Support and strengthen the role that community-based organisations can play in providing culturally informed care to victims of trafficking in their own language to aid recovery and support timely disclosure.

11. The recovery process for victims of trafficking requires a long-term approach, with a diverse range of services and assistance provided over an extended duration. This is particularly important given the length of time that it takes to build trust between support staff and victims, as described by both victims and key informants. Mental health service provision is particularly important given the traumatic experiences of victims in the UK, during their journeys and in the context of their personal histories in their communities of origin. However this research has found that limited availability and capacity of specialist mental health services means that such support is inaccessible for many victims of trafficking. Readily accessible and good quality legal services were also identified as key to ensure that victims of trafficking understand NRM and asylum processes and are aware of entitlements and are able to make informed choices about legal and immigration processes. The complexities of navigating the care, immigration and criminal justice systems was also identified as challenge for survivors in the UK.

- Review structural and policy issues which can impact on long-term service provision to aid recovery, such as Leave to Remain arrangements for victims of trafficking, as identified in Lord McColl’ Modern Slavery (Victim Support) Bill.

- Explore the feasibility of introducing advocates for adult victims of trafficking to help them understand and navigate social care, immigration and asylum processes.

- Provide longer-term funding for complex mental health needs through existing specialist providers trained in working with trauma and past abuse

- Implement trauma-informed approach training programme for staff across all sectors who are working directly with survivors.

- Enhance legal services for individuals referred to the NRM through a national service for potential and identified trafficking victims.

- Ensure that social workers are trained on human trafficking and modern slavery and how to provide appropriate care to survivors as they transition into community settings and access local services.

12. ‘Good practice’ is not defined and is almost absent from debates around human trafficking in all countries considered in this study, including the UK. However, interviewees provided details of pockets of what might be considered emerging, promising or good practice but many of these have yet to be evaluated, making any assessing their actual impact difficult. Similarly, there were mixed opinions on what ‘successful’ short-, medium- or longer-term outcomes look like in practice for victims in the UK, and these are not consistently measured or recorded within the NRM or other systems. Respondents noted that not going missing, or disappearing from view, was an indicator of success, as well as ensuring tenancies were maintained, enrolling adults into appropriate levels of English classes, and gaining Leave to Remain. Questions around where people go beyond immediate or short-term interventions remain.

- Ensure that monitoring and evaluation activities are integrated into interventions so that good practice can be better identified, and to enable successful interventions to be developed, replicated and up-scaled. Ensuring that support organisations are adhering to the updated Slavery and Trafficking Survivor Care standards can be a helpful starting point, but this needs to be complementing by evaluations of which approaches have been particularly effective in different contexts.

- Explore the potential of establishing a framework to understand outcomes for victims of trafficking supported in the UK and for those who may choose to return to their countries of origin.

- Explore potential intersections with – and draw out learning from – other complex social problems, such as violence against women and children which may have a longer history of practice and greater understanding of what interventions can be most effective in particular settings.

Read the report here.