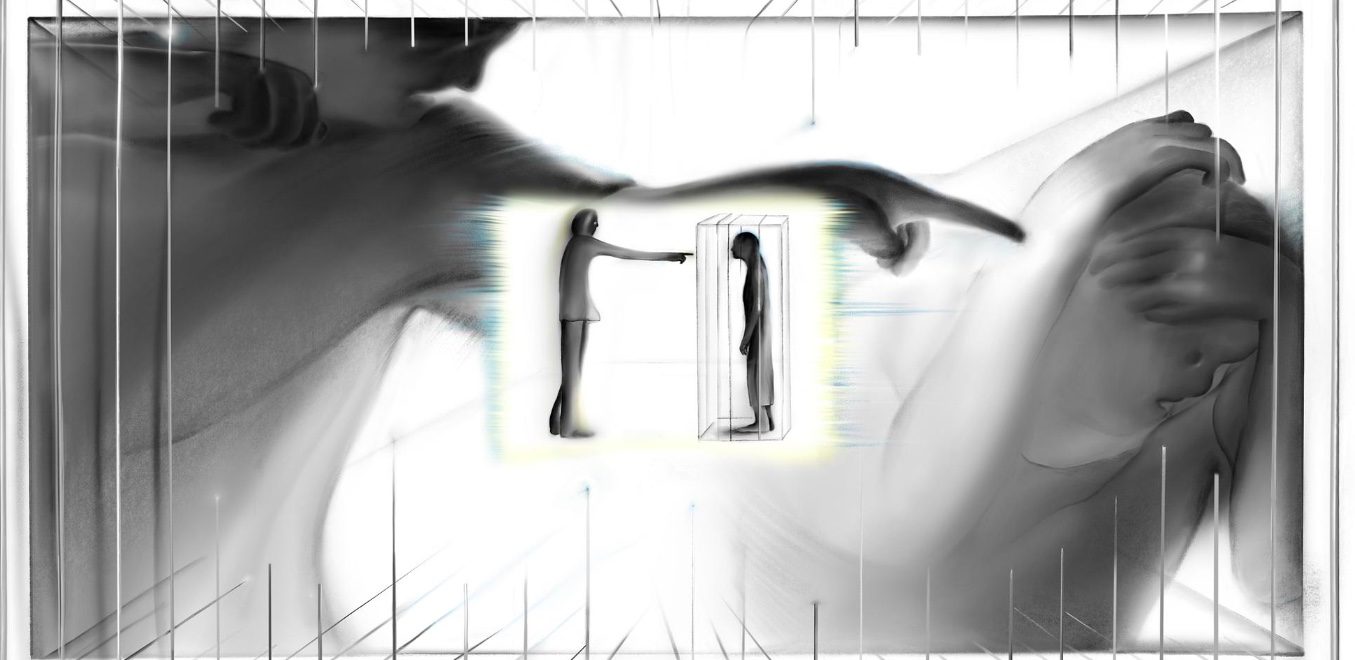

Serving Time for Their Abusers’ Crimes

The Marshall Project found nearly 100 people who were punished for the actions of their abusers under little-known laws like “accomplice liability.”

Pat Johnson counted the locks on the apartment door. One. Two. Three. There were too many to undo and escape before Rey Travieso got to her. He’d just killed three people — including an infant. He turned to her, her face covered in tears and snot. “Don’t worry, Pat, I ain’t going to kill you,” she remembers him saying. “You believe me?”

She didn’t believe him. For seven years, she’d been in an abusive relationship with Travieso. If dinner was not ready on time, he broke furniture and beat her. If she was home after her curfew, he hit her. He had hurt her so badly, she landed in the hospital. She knew what he was capable of.

So she did what he told her to do and helped stuff jewelry and money into a bag, and then she kept her mouth shut.

Even though he did not kill her, in a way, he still took her life. Since 1993, Johnson has sat in an Illinois prison for the murders she said Travieso committed.

Prosecutors didn’t have to prove that Johnson killed anyone to charge her with murder. Under state law, the “theory of accountability” allows a person to be charged for a crime another person committed, if they assisted. That meant Johnson’s charge was murder, and just like Travieso, she faced a life sentence.

Every state has some version of the theory of accountability — more broadly called “accomplice liability” — though the specifics vary from place to place. These kinds of laws can make victims of intimate partner violence particularly vulnerable to prosecution.

There is no comprehensive national data about how many people are behind bars for a crime committed by their abuser due to laws that allow someone to be charged for the actions of another person. Accomplice liability crimes are not usually tracked by the courts as a distinct offense, and domestic violence is often not documented, so it would be impossible to account for every case.

Still, searching through legal documents, The Marshall Project and Mother Jones identified nearly 100 people across the country, nearly all of them women, who were convicted of assisting, supporting or failing to stop a crime by their alleged abuser.