Prison Labor Reformers Hang Hopes on State Anti-Slavery Measures

Voters in a growing number of states have approved ballot initiatives banning slavery or involuntary servitude as a form of criminal punishment, opening new legal ground as part of a larger push to crack down on a prison labor system that pays inmates less than $1 per hour or nothing at all.

During the November midterms, voters in Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont agreed to amend their state constitutions to outlaw the practices. The four states join Colorado, Nebraska, and Utah, which previously approved similar ballot initiatives to abolish slavery and involuntary servitude.

A similar measure failed in Louisiana after supporters later concluded that its ambiguous language wouldn’t actually prohibit involuntary servitude in the state’s prison system.

But while advocates see the measures’ passage as a significant step toward increasing public awareness of prison working conditions, their immediate legal impact is far from earth-shattering.

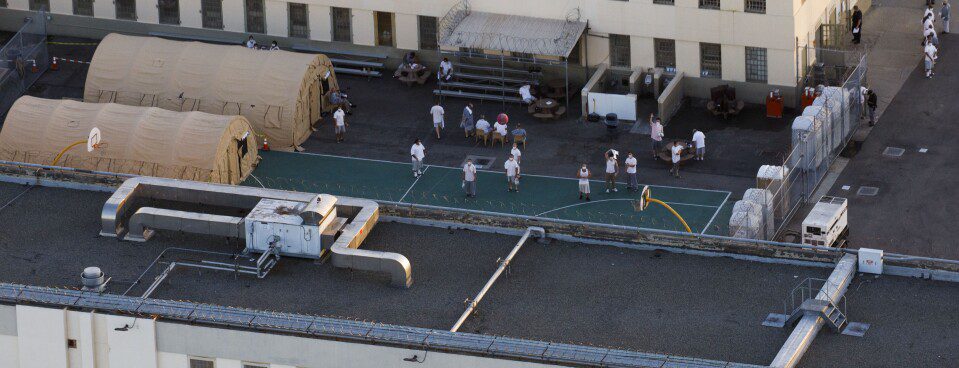

Prisoners—who perform a variety of jobs such as cooking, cleaning, and building furniture—will have to invoke the new amendments in lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of prison labor practices, a process that will take time.

“Nothing is going to change overnight,” said Bianca Tylek, executive director of prison reform advocacy group Worth Rises.

‘Necessary First Step’

Mandatory work requirements are common at prisons nationwide in what’s become a multibillion-dollar practice.

About two-thirds of the 1.2 million people incarcerated in state and federal prisons work, according to a recent American Civil Liberties Union report. These prisoners produce more than $11 billion in goods and services each year, while earning an average of 13 to 52 cents per hour, the report said.

The four states’ ballot measures are expected to invite litigation that ultimately will end the practice.

“These constitutional amendments are a necessary first step in what will hopefully lead to the ending of forced labor for incarcerated workers,” said Jennifer Turner, a researcher in the ACLU’s Human Rights Program and author of the report. “For advocates, this is part of a bigger movement to protect incarcerated workers who are routinely exploited in prisons and jails,” she said.

The cases stand to push courts to rule on what protections, if any, apply to prisoners and “whether the practice of prison labor, as it currently exists, constitutes slavery,” Tylek said.

“Many advocates would absolutely argue that it does, but that hasn’t been established by the courts and that’s the work that’s left to be done,” she said.

Existing Legal Battles

None of the states that have adopted an anti-slavery constitutional amendment has yet changed its prison work rules. But advocates maintain that lawsuits invoking those amendments will help usher in changes.

The success of those lawsuits remains to be seen, however.

In Colorado, a state appellate court in August refused to revive a prisoner’s lawsuit accusing the state of violating its ban on slavery and involuntary servitude.

The court ruled in part that voters didn’t intend to abolish the state Department of Corrections’ inmate work program that the prisoner challenged. Instead, they only wanted to prohibit the imposition of involuntary servitude upon individuals who had been convicted of a crime.

The prisoner, who performed food service work, also didn’t sufficiently allege that the prison work program amounts to involuntary servitude, the court found.

One pending case being closely watched is a proposed class action filed earlier this year, which accuses Colorado prison authorities of violating the state’s ban on slavery and involuntary servitude by forcing inmates to work. The case alleges that inmates are being forced to work despite health concerns, and seeks an order requiring that inmates be paid the minimum wage.

Advocates weren’t aware of similar cases in Nebraska and Utah.

Unintended Consequences

The ballot initiatives received pushback despite broad bipartisan support.

In the Beaver State, the Oregon State Sheriffs’ Association said it doesn’t condone or support slavery and involuntary servitude in any form, but argued that the measure could potentially end reformative programs and increase costs for local jail operations.

Participation in prisoner work programs is voluntary, Jason Meyers, the group’s executive director, said in statement published in the state’s voter guide. But under Oregon’s ballot measure, such a program would likely be considered involuntary servitude if a probation or parole officer doesn’t obtain a court order authorizing an inmate’s participation.

The association didn’t reply to a request for comment.

State officials said the measure won’t require additional government funding, but its impact “will depend on potential legal action or changes to inmate work programs.”

Concerns about cost and legal implications were also a major factor that caused the California state legislature earlier this year to reject a similar ballot proposal. That move came in response the state Department of Finance’s estimation that it would cost approximately $1.6 billion to pay the minimum wage, overtime, and sick leave to the 65,000 incarcerated people there, if ordered to do so by a court ruling.

Legislation Needed

The passage of the state ballot measures follows renewed congressional efforts to amend the 13th Amendment of the US Constitution, which prohibits enslavement and involuntary servitude except as a form of criminal punishment. This exception, which exists in many state constitutions, permits forced labor of incarcerated individuals.

Even if the US Constitution is amended—a long shot—Congress still would need to pass separate legislation to grant labor protections to incarcerated workers and reshape prison labor practices, legal observers said.

Indeed, federal appellate courts have denied claims that incarcerated workers are entitled to protections under the Fair Labor Standards Act, which establishes basic worker protections such as minimum wage, overtime pay, and record-keeping requirements. Congress never intended to include such workers in the FLSA, and the relationship between prisoners and the state is custodial and rehabilitative, courts have held repeatedly.

Congress’ intent was to “ensure a minimum standard of compensation to enable a basic standard of living,” said Andrea Armstrong, a professor at the Loyola University New Orleans College of Law. “The courts said prisons and jails provide basic needs and therefore prisoners were compensated. That’s an interpretation of congressional intent but at no time had Congress said incarcerated people are not employees.”

But Armstrong said federal lawmakers should provide further clarity in legislation, regardless of whether they amend the Constitution.

“It is enormously difficult to amend the constitution whereas passing a new law that recognizes a category of workers as being employees is much easier, procedurally,” she said.

Meanwhile, advocates monitoring the state constitutional amendments’ legal impact are bracing for the long haul.

“The movement for dignity and basic rights for incarcerated workers? is not going to stop just at the passage of the amendments. We know this is going to be a multiyear fight and expect it to be such,” Tylek said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Khorri Atkinson in Washington at katkinson@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Laura D. Francis at lfrancis@bloomberglaw.com; Genevieve Douglas at gdouglas@bloomberglaw.com