Image: The US Southeast and Georgia are experiencing a surge in investment in electric vehicle manufacturing. Photographer: Elijah Nouvelage/Bloomberg

Mexican nationals recruited to work white-collar jobs at Hyundai and Kia plants in Georgia instead ended up on the factory floor, lawsuit alleges.

Isidro Arellano thought he’d found a good thing when recruiters showed up at Mexico’s Universidad Tecnológica de Torreón looking for engineers interested in career-enhancing jobs in the auto industry in the US South.

What the 26-year-old said he got instead was a job lugging steering columns and installing bumpers, logging 60-hour-plus weeks at a Kia assembly line in West Point, Georgia.

“I expected to work in an office, like I was used to in Mexico,” Arellano said from Mexico, where he returned last year after being fired, he said, for complaining about what he describes as a bait-and-switch. “I expected to attend meetings with executives, in an environment that was friendly. I expected what I was promised, what I signed up for.”

Arellano is one of nine Mexican engineers who are plaintiffs in a federal racketeering lawsuit against KIA, an affiliate of South Korea-based Hyundai Motor Group, and Hyundai Mobis, the company’s parts supplier. The Mexican nationals allege they were lured to the companies’ assembly lines by Korean-led labor brokers dangling professional jobs that didn’t exist.

The lawsuit highlights an ongoing battle between business and the US agencies charged with enforcing labor and other laws, including the role of third-party staffing companies in enabling alleged abuse.

The case also comes as the US Southeast, especially Georgia, is experiencing a surge in investment in electric vehicle manufacturing, and it epitomizes a problem many companies and states face as the country pours billions into domestic EV production. It offers a window into how some of the same companies building plants — often in return for substantial state incentives — are having difficulty filling jobs they already have.

Last year Georgia gave its largest incentive package ever, $1.8 billion, to Hyundai for an EV plant near Savannah, promising 8,100 direct jobs and thousands more from suppliers.

“It begs the question, if they are going to make those kinds of promises to the state, why are they engaged in deceptive practices in their existing facilities?” asked Benjamin Botts, law director for Centro de los Derechos del Migrante, the Baltimore nonprofit representing the Mexican nationals.

According to the lawsuit, staffing companies misled both the engineers and the US State Department. It says they coached the engineers on how to obtain TN visas, a professional visa created under the North American Free Trade Agreement, and provided employer letters detailing fictitious US jobs. The plaintiffs were among hundreds of Mexican nationals brought to West Point under the visa program by labor brokers under contract to supply workers to the automakers, the lawsuit says. (The exact number is elusive. Federal officials don’t track TN visa holders in the US) The plaintiffs ended up doing manual labor for less pay and longer hours than their domestic counterparts, the suit alleges.

Kia and Hyundai MOBIS both strongly deny the lawsuit allegations.

“Kia denies the lawsuit’s allegations and will vigorously defend such claims,” the company said in a statement. “Kia requires that its business partners strictly adhere to all applicable laws, including immigration laws.”

In a separate statement, Hyundai MOBIS said that it “is an equal employment opportunity employer. MOBIS denies the allegations contained in the Complaint and will vigorously defend the claim.”

Rapid expansion

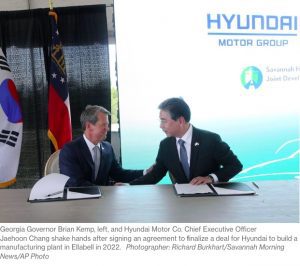

Georgia Governor Brian Kemp has set a particularly torrid pace of recruiting and winning EV projects, making the promised jobs a centerpiece of his 2022 reelection campaign. The ceremonial groundbreaking for the $5.5 billion Hyundai EV plant, the biggest economic development project in state history, came weeks before the Republican governor cruised to victory in November.

The plant has already lured Korean companies that make up much of Hyundai’s Southern US supply chain. Since October, Kemp has announced, among others, 1,500 jobs from Hyundai MOBIS; 630 from Joon Georgia Inc., a subsidiary of Ajin USA; 740 from Seoyon E-HWA and 456 from Ecoplastic. There are an additional 3,500 new jobs at a battery manufacturing plant, a joint venture from Hyundai Motor Group and SK On, a spinoff of Seoul-based SK Innovations. In March, Kemp announced 400 more jobs from a Hyundai supplier. “In a single month, Georgia’s economic development community has announced more than 1,900 new jobs for hardworking Georgians,” most related to the Hyundai plant, Kemp said then.

But even the state’s economist, Jeffrey Dorfman, has warned there may not be enough Georgians to fill the jobs. “I kid the governor about bringing us jobs,” he told state legislators in January. “But we need to bring in more people.”

Georgia’s unemployment rate — 3.1 % in March— is consistently lower than the US average. And nationwide, a labor crunch has plagued automakers for years, said Kristin Dziczek, automotive policy adviser for the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Federal data don’t break out automaking but show the unemployment rate for the general transportation equipment sector — dominated by cars — has been lower than for both manufacturing and overall unemployment nearly every quarter since 2012, she said. As the national unemployment rate averaged 3.3 %, unemployment in transportation manufacturing stood at 1.8 %. “It’s been tight for a long time,” Dziczek said. “All the automakers can tell you.”

The South has added challenges because plants are in rural areas with a far-flung labor pool, she said. “There isn’t a dense, experienced manufacturing workforce around that plant.”

Legally hiring foreign line workers is difficult at best because “there is not a manual labor visa to do those kinds of jobs,” said Charles Kuck, an Atlanta immigration attorney who advises both immigrants and employers.

Visas available for non-agricultural manual labor are for temporary seasonal work, like canning during crab season. They’re also time consuming and costly for businesses, requiring employers to document that no US workers are available and that they pay a prevailing wage. And they’re capped at 66,000 visas annually. Additionally, companies can jump through all required hoops and still end up with no workers.

The TN visa, by contrast, is a breeze. Granted by the US State Department and typically applied for by workers instead of companies, it has no annual cap and none of the worker protections attached to most visas, such as work contracts or prevailing wage and travel reimbursement requirements. Employers provide a job offer letter to U.S. consular officials but nothing else. There is scant federal oversight. There have been more TN visa workers in the US than any other category of temporary visa holder every year except one since 2012, according to data.

The TN visa is for Mexicans and Canadians in specific fields, including scientists, lawyers, doctors, dentists, accountants, architects, astronomers, meteorologists, engineers and others, as well as “scientific technicians” with enough expertise to assist professionals in 10 of the specified fields, including engineering. They are supposed to work in those fields in the US, but no agency systematically checks to make sure they are in the jobs they were brought to the country to do.

According to the lawsuit, the Mexican engineers learned of the Georgia opportunities through LinkedIn, job fairs and universities. A recruiting company identified candidates that met TN visa requirements and coached them through the application process. An affiliated staffing company provided critical hiring letters, attesting to what their US jobs would be.

Luis Salazar, an engineer with seven years of experience, would be a quality control engineer at Hyundai MOBIS “applying statistical methods and performing mathematical calculations to identify the causes of quality problems,” according to his letter, which was included in the lawsuit. He ended up on an assembly line installing bumpers, suspension systems and speakers.

Veronica Olan, an engineer for six years, would “develop, evaluate and improve operations processes;” “analyze, develop and optimize workflows with the production process across all departments to improve efficiency,” and help with “budget, specifications, schedule, management, start-up, evaluations and presentations.” She was put on a KIA assembly line tightening door screws and pouring antifreeze, the lawsuit says.

Arellano, the recruit who expected an office, didn’t even end up at the company his visa specified. He was supposed to be a “scientific production technician” making $40,000 annually with two weeks of paid vacation and a year’s free housing. He said he learned the reality when he landed in a two-bedroom apartment with three other engineers and a job doing manual labor.

Looking ahead

Neither state nor local officials would comment on the specific allegations in the lawsuit or the future implications for Georgia’s labor supply. They said they were taking steps to ensure an adequate workforce for the thousands of coming jobs, including a labor shortage action plan from the Savannah Joint Development Authority, a state rural housing initiative and continued investment in training, especially as related to EVs.

“Georgia is leading the way in growing and developing our workforce to fill the jobs of tomorrow created by valued partners like Kia and Hyundai,” said Garrison Douglas, a spokesman for Kemp.

But the challenge for Georgia and the rest of the US will be long-term and not easily fixed. An estimated 4 million manufacturing jobs will open over the decade, of which 2.1 million will remain unfilled, according to a 2021 report by Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute.

Laine Mears, a professor of automotive engineering at Clemson University in South Carolina — another state pursuing EV manufacturing — called labor among the biggest challenges. The university is working to address it, but “the talent pipeline has slowed to a trickle,” he said. “The question is ‘How do we help revitalize it?’”

The lawsuit, meanwhile, raises questions about the strategies automakers use to staff assembly lines. For example, are companies responsible for labor and other violations when workers are recruited and paid by outside firms? When Alabama fined eight companies in Hyundai’s supply chain late last year for child labor violations, seven were third-party staffing companies that found and hired the children for Hyundai’s suppliers.

Third-party staffing companies have become staples of the US manufacturing industry, said David Weil, a Brandeis economist who headed the US Department of Labor’s Wage and Hours Division under former President Barack Obama.

The Obama administration broadened the definition of responsibility to include the companies where the violations occur, along with the third-party recruiter, in part because of the high level of coordination between the two. Former President Donald Trump reversed the provision, and it was restored by President Joe Biden. Weil’s role in implementing the policy was one of the reasons the US Chamber of Commerce cited in its successful campaign to stop Biden from reappointing him. (The chamber says it hurts small business and franchisees.) The responsibility question has also become an issue in the fight over Labor Secretary nominee Julie Su.

Weil said during his time at the Labor Department, similar problems arose with another visa program, the J-1 visa. The J-1 is a cultural exchange permit intended to bolster educational experiences for international students. That visa, which also is issued by the State Department with minimal oversight, also resulted in foreign students ending up on factory floors a decade ago, Weil said.