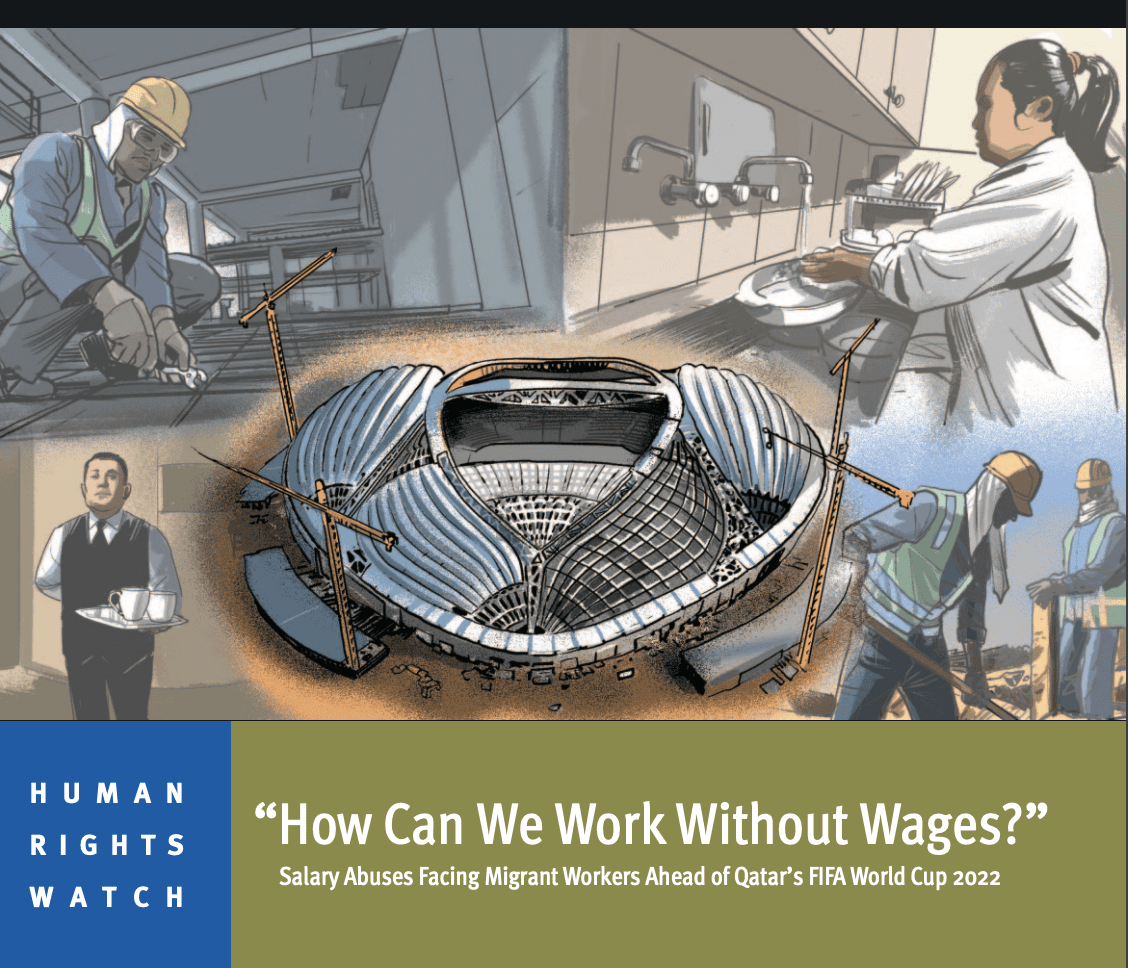

“How Can We Work Without Wages?” Salary Abuses Facing Migrant Workers Ahead of Qatar’s FIFA World Cup 2022

Summary

When “Henry,” a Kenyan man, received the complete list of required documents that allowed him to work in Qatar, he thought all his prayers had been answered.1 To secure a plumbing job in Qatar, he had to take a loan at a 30 percent interest rate in order to pay a Kenyan recruitment agent a fee of 125,000 Kenyan shillings (US$1,173). But Henry, 26, was happy because his employment contract promised him 1,200 Qatari riyals ($329) a month, which would allow him to pay back his loan, plus an additional food allowance, employerpaid accommodation, and overtime payments for each hour of work he performed above the 8-hours-a-day limit.

Upon arriving in Doha in June 2019 however, Henry’s excitement dissipated. The first month, Henry’s employer had no work for him, which meant there would be no pay. The second month, his employer withheld his salary as a ‘security deposit’. To feed himself and his family, Henry was forced to take on more loans. Eventually, in September, he was paid for the first time. But his salary was shockingly low at only 830 Qatari riyals ($228).

For two months, during which Henry performed backbreaking work as a plumber for up to 14 hours a day at a hotel in Lusail city, his employer paid him 30 percent less than he was owed in basic wages. “Where was my full salary? Where was the overtime money and food allowance I was owed? I was shocked, but not alone – the company had cheated 13 Kenyan workers along with me,” said Henry.

While Henry was battling the bitter realities of working in Qatar as a migrant worker, “Samantha” was getting ready to leave Qatar after being cheated of her basic and overtime salaries for two years.2

Between December 2017 and December 2019, Samantha, a 32-year-old Filipina, either scrubbed bathrooms or swept the food court in an upscale mall in Doha. She told Human Rights Watch that her employer made her work 12-hour shifts, had her and her colleagues’ passports confiscated and banned them from leaving the company-provided accommodations for anything other than work.

In 2017, when she had made the decision to leave behind her two toddlers to work in Qatar, she had agreed to work for a monthly salary of 1,800 Qatari riyals ($494). The contract stated that for each hour of work above 8 hours a day, she would be paid 25 percent more than her basic wage. In reality, Samantha worked for 12 hours a day and was paid 1,300 Qatari riyals ($357) a month with no compensation for the overtime work she performed. When she asked why her salary was less than promised and complained that the 25-day salary delays caused her family in the Philippines to starve, her employer told her “to focus on her work silently.” He also withheld her first month’s pay, saying it was “a measure of good faith, a security deposit.” A week before her return to the Philippines, she said her employer informed her he would not be paying her what he owed her in end-ofservice payments, and would use her first month’s salary to buy her return flight ticket to the Philippines, instead of paying for the ticket himself as promised in her contract.

Henry and Samantha’s stories illustrate the wage abuses employers afflict on migrant workers in Qatar today. Qatar’s economy is reliant on some 2 million migrant workers – making up around 95 per cent of its total labor force – who come from countries like India, Nepal, the Philippines, Bangladesh, Kenya, and Uganda to seek better income opportunities. These migrant workers are responsible for building the stadiums, transportation, and hotels for the upcoming FIFA World Cup 2022, and they are almost solely responsible for building the infrastructure and powering the service sector of the entire country. In exchange for this labor, they are only guaranteed a minimum wage of 750 Qatari riyals ($206) per month, which, when paid on time and in full, is barely enough for many workers to pay back recruitment debts, support families back home, and afford basic needs while in Qatar.3 On top of this, employers’ wage abuses leave many in perilous circumstances.

Human Rights Watch spoke to 93 migrant workers working for 60 different employers and companies between January 2019 and May 2020, all of whom reported some form of wage abuse by their employer such as unpaid overtime, arbitrary deductions, delayed wages, withholding of wages, unpaid wages, or inaccurate wages.

The findings in this report show that across Qatar, independent employers, as well as those operating labor supply companies, frequently delay, withhold, or arbitrarily deduct workers’ wages. Employers often withhold contractually guaranteed overtime payments and end-of service benefits, and they regularly violate their contracts with migrant workers with impunity. In the worst cases, workers told Human Rights Watch that employers simply stopped paying their wages, and they often struggled to feed themselves. Taking employers and their companies to the Labour Relations department or the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees is difficult, costly, time-consuming, ineffective, and can often result in retaliation. Workers often describe taking legal action as a “Catch-22” situation – indebted if you do, indebted if you don’t.

The Covid-19 pandemic has amplified the ways in which migrant workers’ rights to wages have long been violated. While none of the wage-related problems migrant workers are facing under Covid-19 are novel — delayed wages, unpaid wages, forceful terminations, repatriation without receiving end-of-service benefits, delayed access to justice regarding wages, arbitrary deductions from salaries — since the pandemic first appeared in Qatar, these abuses have appeared more frequently.

While each migrant worker had a unique story, the wage abuses they face reflect a pattern of abuse driven and facilitated by three key factors: the kafala (sponsorship) system, a migrant labor governance system in Qatar; deceptive recruitment practices both in Qatar and in workers’ home countries; and business practices including the so-called ‘pay when paid’ clause, which requires the subcontractor to delay payments to workers and leaves migrant workers vulnerable to payment delays in supply chain hierarchies.

Read more here.