Jovani Chilhueso (left), seen here with his father, was paid $400 (£330) to join a gang and lost friends as young as 11

Corinto has the vibe of a bustling town just like any other – motorbikes zip up and down the main streets, residents amble along the pavements and shop owners hover outside their premises, beckoning in customers.

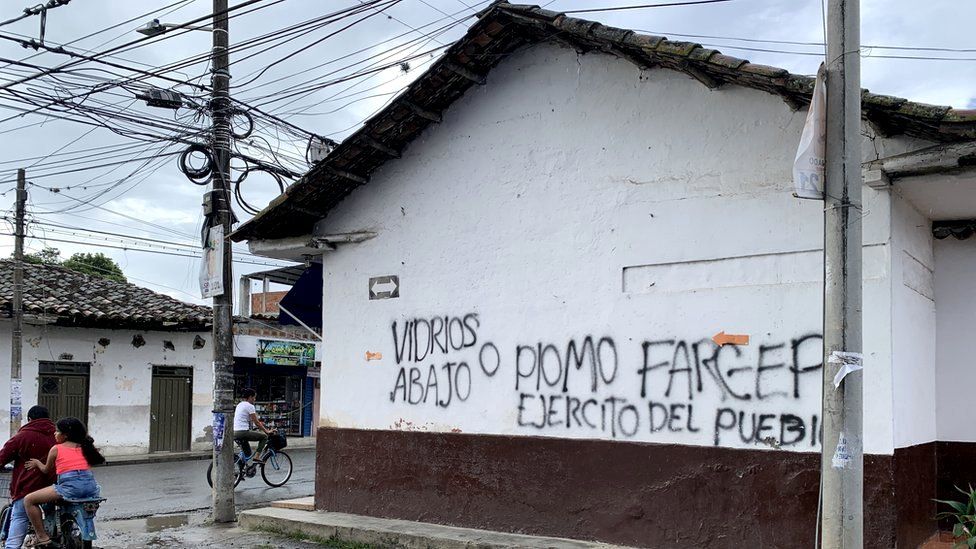

But stop on any street corner and there is a more threatening presence here.

“Windows down or bullets,” reads one graffitied wall, and it is signed “FARC-EP”, short for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – the People’s Army. It is a warning to drivers to make themselves known and is repeated on many walls in Corinto, in Colombia’s south-west Cauca province.

The Farc guerrilla group demobilised in 2016 after signing a peace deal with the government. It ended more than five decades of civil conflict. But nearly six years on, the deal is yet to be fully implemented, and while violence overall has fallen since the peace deal, what is happening in rural Colombia is alarming experts.

Farc members who did not agree to the peace deal, right-wing paramilitaries, and newer criminal groups that have since cropped up are all vying for territory that was once controlled by the guerrilla group – and they are all on the lookout for new recruits.

According to the UN, some 600 children were recruited by armed gangs in the three years after signing the peace deal – a number experts say is vastly underestimated.

Those most likely to be targeted are poor Colombians living in rural areas where Farc once operated. The most vulnerable are indigenous children.

One 13-year-old, Derli (not her real name), is part of the Nasa indigenous group which has traditionally stood up to armed gangs. A quiet teenager, Derli is wearing a pink T-shirt printed with the words “only love”. It is a jarring phrase given the context of the conversation taking place.

Derli ran away from home because of a fractious relationship with her mother. She was tempted by money offered by Farc dissidents and because some of her friends had gone before her. But she soon regretted it.

“We learned how to use guns, learned how to kill people and tie them up,” she says, constantly wringing her hands with nervousness as she recounts her story.

“They tied me up, made me starve,” she adds. “They always said this life was for the tough guys – I had to drive a motorbike while they executed someone. I never wanted to do that but if you didn’t they would punish you… or kill you.”

From the window, Derli shows me the mountain where they took her. She says she was rescued one night by the head of the indigenous group after he was contacted by a female fighter who took pity on her.

But even when she was home, her nightmare continued.

“I got death threats from the group,” she explains. Then one morning, she woke up to find the armed group surrounding her house. “My family hid me in a room.”

Former Farc member Boris Guevara left the guerrilla group in 2016

Former Farc member Boris Guevara left the guerrilla group in 2016“It’s not got better, it’s got worse,” says Luz Marina Escué, a community leader who helps indigenous elders track down vulnerable children – either before they are recruited, or to rescue them afterwards.

“The gangs come along, take out wads of cash, tell the kids to buy what they want,” she says. “It’s no longer a guerrilla that fights for the people, because it’s killing the people.”

That is a feeling echoed by former Farc member Boris Guevara. He joined the guerrillas when he was 16, but laid down his weapons in 2016.

“Farc never paid. Every economic activity was to maintain the army, not to pay soldiers,” he says. “I never received a peso to do the job I did. That’s caused a big divide – between becoming paid mercenaries and a political conscious where you’re making sacrifices for something you believe in.”

According to Luz Marina Escué, the act of recruiting children to these groups is wiping out Colombia’s future.

“They are the seeds that are going to work our land,” she says, shaking her head. Much of the land, however, is still full of illegal crops.

Across the valley, there are coca and marijuana plantations. Not all of these fields are hidden away – we saw many on the side of the road. Come sunset, the hillsides are illuminated by light bulbs suspended over marijuana crops.

The peace deal was meant to rein in cocaine production, but it just keeps soaring. According to the White House, Colombia produced about 972 tonnes of coca in 2021 – 10 years ago that figure was 273 tonnes.

The farmers here carry on – when you get just 15 cents for a kilo of oranges but coca or marijuana pays you hundreds of times more, it is hard to say no.

“We aren’t narcos,” says Irma Corpus, a cocalera, or coca farmer. As part of the peace deal, voluntary crop substitution was encouraged, but many in the fields feel the government has failed to fulfil its side of the bargain.

Farmers like Irma say they have no option but to continue planting illegal crops

Farmers like Irma say they have no option but to continue planting illegal crops“Of course we agree with eradication but it needs to be gradual, we don’t have alternatives,” says Irma. “The peace deal itself on paper was very elegant – we were promised everything – but actually, it delivered nothing.”

It is young Colombians who are paying the price. Jovani Chilhueso was handed $400 (£330) to join a gang. He has lost friends as young as 11 to the violence.

“When I picked up my first gun, I felt adrenalin,” he says. “It was something I liked, I wanted to shoot more and more but the reality is, a fight isn’t the same as just shooting alone.”

His father, Daniel Rivera, is an indigenous guard, protecting his community from the likes of armed gangs. He did not expect his son to join one.

“I felt such sadness and pain, thinking I might lose my son,” Daniel says. “The first thing you think is how did I fail? What did I do wrong?”

But in these parts of Colombia, the right path is a hard one. Many people hope that the new president being sworn in this weekend, Gustavo Petro, fulfils his campaign promises to end the violence and offer young people a chance to shape their future.