Jalandhar (India) and Latina (Italy): In October 2022, when Kamaljit Singh and Joginder Singh found work at a kiwi farm in Italy’s Lazio region, they heaved sighs of relief.

After nearly a year of working odd jobs around the country, they finally had monthly contracts promising them wages of 6.5 euros an hour.

The two men did not care that they would not be issued equipment and tools such as raincoats, scissors and boots, which are needed to work in the kiwis in Italy.

They did not even care that the official wage for agricultural workers is nine euros an hour, while they were offered just a little more than half that amount. “The mere thought of earning around 1,100 euros a month (about Rs 95,000 a month) was enough to make us feel good,” they said.

In any case, they would never make a fuss about their working conditions, they told The Wire. If they did, they might be sacked. Or worse, reported to the police and deported.

Kamaljit and Joginder are just two of the thousands of Punjabi workers who move to Italy illegally, trying to make a good living for their families back home. They know what exploitation is because they have suffered it from the moment they decided to work abroad. But for the moment, exploitation works for them. Because they are willing to bring down their employers’ overheads by accepting lower wages and a less safe work environment than the local labour force, they are in demand. And they will earn more in three months than they might earn in three years back home.

Fields of Plenty

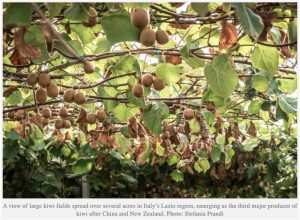

Italy is the leading producer of kiwi fruit in Europe, the third largest producer of kiwis in the world after China and New Zealand, exporting about 3,200,000 tons to 50 countries around the world with a turnover of more than 400 million euros.

The demand for agricultural labour in the kiwi growing regions of the country is intense during the harvest season, beginning September-October. That’s when the migrants get regular work, sometimes by word of mouth, but mostly via brokers or middlemen, who are usually fellow Punjabis.

“In the harvest season, it is impossible to know the number of labourers in the kiwi fruit fields,” said Laura Hardeep Kaur, a member of the trade union Flai Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro (CGIL). “That’s because they often work illegally.”

A significant percentage of Indians from Punjab, mostly from the Sikh community, are employed in the kiwi farms, said Giorgio Carra, secretary general of the Italian Union of Agricultural and Food Workers.

According to data from the National Institute of Social Security (INPS), there are nearly 9,500 Indian agricultural workers in the province of Latina, where Lazio, with its 6,000 registered kiwi farms, is located.

However, according to Marco Omizzolo, a professor of sociology at Rome’s La Sapienza University who specialises in the socio-political implications of migration, the INPS has underestimated the numbers.

“There could be twice as many Indian workers,” Omizzolo said. “My estimate includes those without residence permits, residents in other provinces, and those who have recently arrived, but are undocumented.”

Omizzolo, who is also an activist, is so involved in stopping the exploitation of migrant labour in Italy that he has become the target of death threats from the mafia of the middlemen who supply farms with labour and has been under police protection for a long time.

Emigration fraud

Kamaljit is from Punjab’s Jalandhar region, while Joginder is from Nawanshahr district. Like many other illegal immigrants from Punjab, they decided to emigrate in the period just after COVID-19, when employment at home was harder to find than usual.

From the moment they made their decisions to move, they began to be exploited.

First, when they acquired work visas for Romania from a Jalandhar-based travel agent in December 2021 after the agent promised them jobs at a Chinese firm in the East European country, they each had to pay the agent Rs 3.5 lakh. Next, within a few days of their arrival in Romania, they realised they had been duped. The firm that had ’employed’ them did not exist.

They could have returned to India then, but having got so far, Kamaljit and Joginder decided to take what is called the ‘donkey route’, to Italy, paying ‘donkers’ or traffickers Rs 4 lakh each for the journey.

A donkey or illegal route to a West European country involves enormous expenses and life-threatening conditions: people trek for hundreds of kilometres to cross borders or are loaded into overcrowded, suffocating trucks or sea vessels to get where they want to go.

No safety regulations apply because the entire enterprise is illegal. There is no guarantee either that the people using these routes will even arrive at their destination. The emigrants’ grapevine is also filled with tales of people having lost their lives on these journeys. But when legal means of emigration are impossible, those in need of work will do what they must based purely on hope.

Italy was Kamaljit and Joginder’s preferred destination because, with migration taking place over decades, the country had a large population of Punjabi workers who would take them in and help them find work.

“We call this ‘infrastructure migration’,” explains Professor Virinder Singh Kalra of the University of Warwick in Coventry, UK. “If you’re Punjabi and you turn up in Italy, you can stay in one of the gurdwaras there and find food. Generally, it’s very hard for the first group of people who emigrate because they have to settle, find work and housing. But once one group has settled, they invite their relatives and friends and the cost of migration for the second group is much lower because they will stay with their relatives and get work with them. And then there will be a third group and so on. By now, anyone from the community who turns up in Italy knows they will be looked after.”

But Kamaljit and Joginder believe this is better than working in India. “What will you do with the meagre salary of Rs 7,000 a month?” said Kamaljit. “That’s what I was being paid when I worked at a cardboard factory in Nawanshahr district. Given my family’s financial condition, it was not easy to arrange the money and move abroad, but I am glad I am finally in Italy.”

Joginder worked as a carpenter in Jalandhar, earning about Rs 10,000 a month. “I come from a family of labourers,” he told The Wire. “My father died some years ago and my elderly mother, who is usually ill, is dependent on me for her treatment. It will take time for me to get permanent residency in Italy, but I think the struggle was worth it. I am earning better here.”

In a house partly under construction in a narrow lane in Amritsar, Jaswinder Singh, a resident of Gurdaspur district whose brother Sukhbir Singh is now working in Italy, was eager to explain why Punjabis are so keen to work abroad.

“If there were enough jobs here, why would anybody move abroad?” Jaswinder asked. “Among my family, I am the only one who knows how my brother got to Italy. He made two donkey attempts and got there on the second one. But he faced life-threatening hardships on both trips. It was disheartening to hear his story but finally he is settled and able to send home some money.”

Jaswinder had participated in the historic farmers’ protest in Delhi in 2020-2021 which garnered worldwide attention. He camped at the borders of Delhi for a year, protesting the three farm laws introduced by the government without the farmers’ involvement. But when the government withdrew the laws and the protest ended, he returned home to the same conditions he had faced in the first place. “There is no hope. We demand Minimum Support Price for all crops but the government is not bothered,” he said. “What else can people do but move abroad for a better and more stable life?”

The migrants’ pain

Unfortunately, emigrants from India know that while working illegally in a foreign country may make life better for those left at home, their own lives have little stability and often, no justice.

Gurjinder Singh, for instance, has worked in the kiwi farms of Lazio for 15 years, and has never earned more than five or six euros an hour at any time.

In the smaller companies, he never had a contract and pay was delivered in cash at the end of the day. And at one company, where he worked for three years along with more than 70 other laborers, his supervisor filmed him with her cell phone whenever he stopped to drink water or to clean dirt from his eyes. These videos were sent to the head of the company as ‘proof’ of Gurjinder’s poor performance to avoid paying him for those days. They were also used as a ‘warning’ for other workers.

Though Gurjinder sometimes thought of quitting his job with this company, he knew he could not. “I had no choice. I had to earn for my four children and my wife in India,” he said. The last time he saw his family was 13 years ago, since working in Italy without a contract means he is not eligible for a residence permit, which in turn means he will not be allowed to return to Italy after a trip home.

“We were poor when I left India,” Gurjinder said. “To get here, I gave a trafficker 14,000 euros. I came via Russia, first walking in the snow for miles and then loaded into trucks in which people were dying from lack of air.”

Despite his many years in Italy, Gurjinder does not speak much Italian. In the workers’ camp where he lives, no one is allowed to learn the language. If an Indian were to speak Italian, he would risk being sacked by his supervisors, because he may then be able to establish a direct relationship with the company head and get the supervisors in trouble.

Kamaljit Singh, who works for a company called Gik, said, “They won’t let us team up. They keep changing the composition of the teams so we can’t talk to each other.”

Elsewhere in the region, another illegal Indian immigrant named Balbir Singh had no choice but to bring his working conditions to the notice of the authorities because his employers had taken away his passport and virtually incarcerated him. Balbir Singh’s courage in standing up for himself was ultimately rewarded when an Italian court granted him a long stay visa for “reasons of justice”.

“I feel like a free man,” Balbir Singh told The Wire during an interview when he returned to Punjab in October 2022 to visit his family. “Now I want to take my wife to Italy and settle there permanently.”

In Italy’s Aprilia region, best friends Balkar Singh and Udham Singh worked in kiwi farms for 18 and 13 years respectively before quitting to work at grape farms. Despite their long experience working with kiwi fruit, they never earned more than 5.50 euro per hour.

“To avoid tax, our employer paid us 700 to 800 euros per month as salary and another 100 to 200 euros in cash,” Balkar explained. “He paid us the cash at the beginning of each month. It is a common practice among farm owners here. Their idea is to evade hefty taxes.”

Though Balkar and Udham understood they were being exploited, they did not mind. “For us the main concern was stable work and money. We shared a good bond with our employer,” Balkar said.

Having lived and worked in Italy for so long, the two of them know how the farm owners operate. “It is the small kiwi farms that usually hire illegal workers,” said Udham. “Either they hire them for two to four days at a higher wage, or take them on for longer durations for 500 to 800 euros per month. The bigger kiwi farms do not hire illegal workers.”

Tangled operations

The biggest buyer of the kiwi fruit produced in Lazio is Zespri, a New Zealand-based multinational which sells 10.5% of the produce under its own brand name.

Between September and November every year, the landscape of Lazio is composed of rows of kiwi fruit bushes. Between these rows are bins in which teams of labourers collect the fruit. The bins come in several colours, each colour representing the producer organisation through which the kiwis destined for foreign markets pass. Fourteen producer organisations are licensed to sell Zespri’s kiwis.

The multinational company owns the patent for the kiwi fruit and determines the number of hectares on which the fruit will be grown. It then distributes licences to the cooperatives, which in turn seek the “best” farmers to grow the fruit. The producers do not pay for the licence, but are required to become members of the cooperatives that bear the costs of packaging the fruit.

From the fields of small and medium-sized farms, the kiwi fruit are taken to the large warehouses of the producer organisations where they are either frozen and stored or loaded onto trucks and transported to plants in northern Italy, especially in Emilia Romagna, owned by the cooperatives. There they are packed and, once stamped with the Zespri brand, become Zespri kiwis.

Marco Omizzolo calls this kind of operation, where those who produce sell to another producer who in turn resells to a brand, an “entrepreneurial skein”, meaning that with so many elements involved in the supply chain, the thread of compliance and accountability is lost.

With two and a half billion euros in sales between 2021 and 2022 and more than 200 million crates of kiwi fruit sold worldwide, Zespri is best known for its yellow-fleshed variety – a patent of theirs – the “SunGold”. This is the most planted variety of kiwi fruit in the Agro Pontino region of Italy.

In 2019, there were 2,700 hectares of SunGold kiwi fruit in Italy, and the company’s goal is to acquire 5,400 hectares by 2025.

Since samples are taken from each row of bushes, harvesting can begin at different times even on a single farm. The rules are strict: cotton gloves and delicate, precise manoeuvres are required; it is essential not to spoil the fruit when placing it in boxes.

The care for the fruit is in stark contrast to the conditions of the labour. “They always want you to work fast, they shout at you to hurry up. When they pay you, they take a few hours out of the pay cheque. And they don’t pay you for all your days of work,” said Amandeep Singh, formerly employed in Cisterna di Latina in a consortium that produces kiwi fruit directly for Zespri.

Amandeep has worked in Italy for 20 years and claims that he has been treated badly all the time. Workers like him have had to accept wages as low as 4.50 euros per hour in order to get a contract. Without a contract, they cannot renew their residence permit. Their working days could be ten hours long for seven days a week, far beyond the limits imposed by the provincial labour contract.

“In my pay cheque, they would write 600-700 euros and give me 200-300 euros off the books, not paying me for three to seven hours of work,” Amandeep explained. “The system is the same everywhere.”

Amandeep spends time at a gurdwara in Velletri, one of the many gurdwaras scattered about the Latina province. Meals are prepared here at all hours for worshippers and anyone in need and people often drop by to distribute food and drink. “I lived here for two years, without paying for rent, food and electricity, because I could not afford a house,” said Amandeep. “I’ve been in Italy for 20 years and I’ve seen at least 700 people in the same condition as me.”

Thanks to the “entrepreneurial skein” of the kiwi fruit supply chain, there is very little accountability in labour matters. “When a lot of producers bring harvests to the big companies, there is a quality control system in place. However, not much attention is paid to how small producers treat their workers,” explained Giovanni Gioia, secretary general of the Frosinone-Latina CGIL, a local department of the trade union CGIL.

Periodically, there are reports of accidents at work. A report by the Foundation Observatory on Crime in Agriculture and the Agribusiness System, in collaboration with the Lazio Region and the Ministry of Ecological Transition, on illegality and criminality in agribusiness supply chains in the province of Lazio states: “Despite the fact that 92% of the labourers interviewed reported using gloves and work shoes, it does not appear that the companies in which they worked ever informed them about safety risks or applied preventive measures, such as masks and protective clothing.”

Zespri responds

Asked about the irregularities found in the companies licensed to produce its kiwi fruit, Zespri replied: “While the vast majority of employers in the kiwi fruit industry take care of their employees, a small minority may not. Any exploitation of workers is unacceptable and we are committed to holding those involved to account and continuing to improve our compliance systems to help us do so. We take the allegations extremely seriously and have launched an investigation into the matter, also to understand how best to support the workers involved.”

According to the multinational, their suppliers are registered with Sedex, “a leading ethical trade organisation focused on improving working conditions in global supply chains”. Through Sedex, the Italian suppliers of SunGold kiwi fruit are externally audited by a third-party certification body and annually confirm their acceptance of the Zespri Supplier Code of Conduct.

Zespri claimed to have contacted both its suppliers and the certifiers “to make them aware of the alleged unfair practices” reported in this investigation. The company added that they invite “anyone in possession of information relating to illegal practices” to contact the company via “the confidential EthicsPoint – Zespri International telephone line”. The multinational also claimed to have created its own “task force to review Zespri’s [supplier companies’] regulatory compliance programmes globally and identify initiatives and/or improvements to be introduced in the first half of this year”.

While Zespri’s responses appear to be sincere, the multinational failed to comment on the finding that Craig Thompson, director of Zespri Group Limited and Zespri International Limited, who earned 66,000 euro in these positions in 2022, is a shareholder of one of the kiwi producing companies whose labourers were interviewed in this investigation. Thompson is a member of the agricultural society named Gik in Cisterna di Latina, which is owned by the consortium where Mandeep Singh and Rishi Singh work for 6.50 euros an hour without adequate safety devices.

Though Gik was contacted to discuss the statements of its workers, it did not respond.

This investigation has been conducted jointly by The Wire, Danwatch and IRPI Media with the support of the Journalismfund Europe.