A New Lens on Forced Displacement

Article from Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security

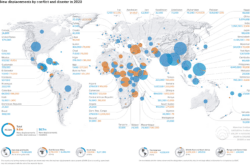

Forced displacement has moved up the global agenda as the number of displaced people has continued to rise, approaching 90 million at the end of 2020. About 55 million—most of the displaced—remained in their own country as internally displaced persons (IDPs). About 48 million IDPs were displaced by conflict and violence and about 7 million by natural disasters. And of the 1.44 million refugees in urgent need of resettlement globally, only 23,000 were resettled in the past year, the lowest number in almost two decades, according to estimates by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

Constructing the forcibly displaced WPS Index

To better understand challenges to inclusion, justice, and security for displaced women, we constructed WPS indices for five African countries with high levels of displacement: Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan. The World Bank’s new high frequency surveys enabled separate estimates of the WPS Index for displaced and host community women in those countries. The surveys investigated are the Ethiopia Skills Profile Survey (2017), covering refugees from four countries living in Ethiopia in camps and the surrounding host communities; the Nigeria IDP Survey (2018), covering IDPs and host communities in the northeast; the Somalia high frequency survey (2017), covering internally displaced and host communities nationwide; South Sudan’s high frequency survey Wave 4 (2017), covering urban IDPs and host communities in seven states; and the Sudan IDP Profiling Survey (2018), covering IDPs living in the Abu Shouk and El Salam camps in Darfur and the host communities around Al Fashir. The data from these surveys allow tracking the impacts of conflict and displacement, which can inform policy and programmatic responses.

Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan had large numbers of displaced people even before the tragic conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region in 2021. UNHCR estimates that in Somalia, almost 3 million people (19 percent of the population) were internally displaced as of January 2021 due to drought, flooding, famine, and armed and clan conflicts. The 2017 drought in Somalia, followed by extreme floods in 2018, displaced more than 926,000 people.

To assess the differences between the experiences of displaced women and those of host community women, we measured the differences in inclusion, justice, and security between displaced women and host community women. As far as we are aware, this is the first attempt to comprehensively capture and quantify the relative status of forcibly displaced women through a gender-focused index.

The indicators used in the forcibly displaced index are similar to those in the global index, with some adjustments for data availability and relevance. The inclusion dimension considers women’s mean years of schooling, employment rates, cellphone access, and financial inclusion. The justice dimension captures women’s possession of legal identification, legal protections, and ability to move freely. The security dimension takes into account community safety, measured as the share of women who do not feel safe walking alone in their neighborhood at night, and current intimate partner violence. Most data come from high frequency surveys carried out by the World Bank that were designed to cover IDP communities, while the data on intimate partner violence and legal discrimination were drawn from other published sources.

Our data predate the pandemic, which emerging evidence suggests is compounding the disadvantages facing displaced women, who are enduring the triple challenges of gender inequality, displacement, and COVID impacts. A new International Rescue Committee/Overseas Development Institute report surveying conditions in Greece, Jordan, and Nigeria reveals that displaced women have been less likely to earn income or be employed during the pandemic than men, in part because they rely heavily on the informal labor market for work. In Nigeria, 75 percent of displaced women reported struggling to cover their basic needs during the pandemic, and in Greece, only half of displaced women felt that their current wages were enough to meet their household needs.

To capture the legal situation of displaced women, we combined seven elements, equally weighted and taking into account the rights of both refugees and IDPs, to generate a new measure of legal protection. Refugees’ rights to work in the private sector, to own property, and to choose where to live were drawn from the Migration and the Law database of the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development. For IDP-specific aspects, we counted whether the country has ratified the Kampala Convention, whether national legislation protects IDPs, and whether there is a national policy addressing IDP-related issues. To capture gender discrimination in national law, we used the absence of legal discrimination as measured by the Women, Business, and the Law score and incorporated in the global WPS Index. Scores out of seven were translated into summary percentages to factor into index scores.

Among the five countries, Ethiopia had the highest score, 93 percent, and Sudan had the lowest, 29 percent. These scores are national and do not differentiate by gender, but they do provide insight into displaced women’s legal setting.

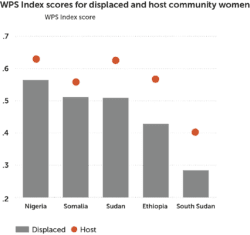

Forcibly displaced women generally did worse

In all five countries, WPS Index scores were worse for displaced women than for host community women, with an average disadvantage of about 24 percent. Across the five countries, displaced women generally faced much higher risks than host community women of violence at home, were consistently less likely to be financially included, and often felt less free to move about.

Displaced women’s disadvantage was greatest in South Sudan, where their score (.284) fell about 42 percent below that of host community women. On our global WPS Index, the country ranks third to last. The poor performance for both forcibly displaced and host community women underlines the scale of deprivations in the conflict-affected country.

Differences in Ethiopia between refugee and host community women were also wide—around 33 percent—despite few formal legal barriers separating them. The rate of financial inclusion among displaced women was minimal, at around 2 percent—the lowest in our five-country sample and around 25 times less than the rate among host community men and women. Although a 2019 law in Ethiopia allows refugees to work and open bank accounts, implementation has been delayed, and the mobile money market is nascent. Social norms and a lack of financial and digital literacy disproportionately obstruct displaced women’s access to financial services. Only one refugee woman in five felt free to move where she chooses, and 26 percent felt unsafe walking in their neighborhood at night, more than double the share for host community women, highlighting severe barriers to mobility and security for refugee women.

Refugee women in Ethiopia were more likely to have a form of legal identification than host community women (54 versus 36 percent). This could be linked to a national policy introduced in 2017 that allows refugees to obtain birth, death, and marriage certificates. UNHCR’s ongoing programming also aims to help refugees obtain digital identification—as of April 2019, approximately 500,000 refugees in Ethiopia had been registered this way.

Employment rates are low in Ethiopia, pointing to generally limited livelihood opportunities. Employment rates ranged from 7 percent for displaced women to 24 percent for host community men. Recent analysis of displaced women in Ethiopia found that the length of displacement had a significant impact on their employment prospects—women displaced for at least three years were more likely to be in paid work than those recently displaced. This suggests that, over time, women are able to assimilate into their communities and pursue economic opportunities. The analysis also shows that education boosts economic opportunities for refugee women in Ethiopia.

The countries with the greatest disparities in WPS Index scores between displaced and host community women—Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Sudan—are also the countries with the widest multidimensional poverty gaps between displaced and host community populations. In all five countries, female-headed refugee/IDP households were also more likely than male-headed households to be poor, showing how gender inequality compounds the effects of displacement and poverty.

In refugee households in Ethiopia, 58 percent of female-headed households were impoverished, compared with 19 percent of male-headed households. Lack of physical safety, early marriage, and lack of legal identification were the largest contributors to poverty in households headed by displaced women.

We found the smallest gap in WPS scores in Somalia, where displaced women were about 9 percent worse off than host community women. Both groups had similarly low rates of access to legal identification (14 percent). Because of protracted conflict and poor government administration, fewer than 1 birth in 10 in the country was registered, and there is no national system of identification. Additional reasons reported for not having legal identification in Somalia included lack of trust in the government, absence of legal protections for personal data, and high costs. Displaced and host community women in Somalia also had similar rates of employment, mobility, and community safety, with gaps of less than 5 percentage points.

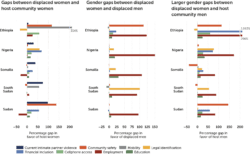

In Nigeria, the gaps between displaced and host community women averaged about 12 percentage points, with relatively large disparities in cellphone access (11 percentage points) and legal identification (15 percentage points), while rates of employment and mobility were similar. Gender gaps were small for cellphone access, financial inclusion, mobility, and community safety, but wide for employment, concurring with other analyses finding wide gender gaps in employment in northeast Nigeria for both displaced and nondisplaced populations. In data collected by the International Rescue Committee and the Overseas Development Institute in 2021, 43 percent of displaced women in Nigeria lost income during the COVID pandemic, while 29 percent reported having to give their earned money to their husband or encountering other controlling behaviors.

Across all five countries, displaced women fared systematically worse than host community women in financial inclusion and risk of intimate partner violence (figure 3.4). The gaps between refugee and host community women’s rates of financial inclusion exceeded 15 percentage points in Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Somalia, compared with 4 percentage points in Sudan.

The security dimension results highlight the risk that displacement will compound women’s insecurity. In all five countries, levels of current intimate partner violence were higher among displaced women than among women in the host population. In Somalia, 36 percent of displaced women experienced intimate partner violence, compared with 26 percent of host community women, a difference of 38 percent. In South Sudan, 47 percent of displaced women had experienced intimate partner violence in the past year—a rate nearly double the national average of 27 percent and quadruple the global average of about 12 percent.

These results are consistent with accumulating evidence—in settings ranging from Colombia to Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Mali, and Nigeria—documenting how displacement and instability significantly increase the risk of intimate partner violence. A recent study from Democratic Republic of the Congo found that both former and current displacement significantly worsened women’s risk of intimate partner violence in the past year, as well as other forms of gender-based violence such as rape. Displaced women in Colombia and Liberia had 40–55 percent greater odds of experiencing past-year intimate partner violence than their nondisplaced counterparts. A quasi-experimental study in Mali examining changes in intimate partner violence risks as the country became unstable found that women living in conflict-affected areas were significantly more likely than their counterparts outside such areas to experience multiple forms of intimate partner violence. These studies highlight the important linkages between violence at the community level and violence in the home.

In Nigeria and Somalia, displaced and host community women had similarly high levels of perceived safety, with only 5–8 percent reporting feeling unsafe in their neighborhood at night. This contrasts with Ethiopia, where about one displaced woman in four felt unsafe in her neighborhood, more than double the rates for displaced men, host community men, and host community women, suggesting that gender inequality and displacement can intersect to threaten women’s safety.

By contrast, displaced women in South Sudan were less likely to feel unsafe than host community women, though rates were extremely high for both groups at 78 percent for displaced women and 86 percent for host community women. Interestingly, gender gaps on this indicator in South Sudan were relatively small, with both displaced and host community men reporting rates within 2 percentage points of women’s rates, suggesting pervasive perceptions of insecurity. The somewhat higher sense of safety among displaced women may be due to residence in camps, which could provide protection and security amid the ongoing conflict.

The results for the justice dimension reveal that the five countries generally have good laws on paper protecting internally displaced persons and refugees. All five countries in the analysis except Sudan have ratified the Kampala Agreement, a regional commitment protecting IDP rights, and all countries except South Sudan have published a national action plan on IDPs, signaling commitment to protecting their rights.

But in Ethiopia, only about one refugee woman in five felt free to move where she chose, compared with 94 percent of displaced women in Nigeria and 86 percent in Somalia. Ethiopia’s low score on mobility contrasts with its high score on legal protection (93 percent), pointing to gaps between protection in principle and rights in practice.

Gender gaps compound disadvantages

The gender gaps facing displaced women were greatest for employment. Across all five countries, employment rates were at least 90 percent higher for displaced men than for displaced women—nearly 150 percent higher in Nigeria, where about 36 percent of displaced men were employed, compared with about 15 percent of displaced women. The gaps reflect the broader fact that labor markets around the world remain highly segregated by gender—with women more concentrated in unskilled and low-paid sectors than men, a condition that also tends to make it hard for refugee women to find jobs. Other obstacles such as language barriers, lower literacy rates, unpaid care responsibilities, and gender norms that limit women’s mobility can compound the constraints on refugee women’s economic opportunities.

Comparisons between displaced women and host community men exposed even starker gaps, highlighting the multiplying effects of displacement and gender inequality. In Ethiopia, for example, the share of employed host community men was almost three times the share of employed refugee women. The results suggest that even in countries where displaced women are legally permitted to work (the case for all five countries in our analysis), many face discriminatory norms and regulatory barriers. The impediments affect the economy at large. For example, estimates by the Georgetown Institute on Women, Peace, and Security and the International Rescue Committee suggest that if gender gaps in employment and earnings were closed in the top 30 refugee-hosting countries, refugee women could generate $1.4 trillion a year in global GDP.

Our results underline the added challenges related to inclusion, justice, and security for displaced women, highlighting the intersecting and compounding challenges of gender inequality and forced displacement. At the same time, the range of performance, both overall and on specific indicators, demonstrates the complexity of each situation. In Somalia, for example, displaced women had relatively high rates of financial inclusion but had the lowest rates of legal identification among the five countries. Nigeria had the lowest rates of intimate partner violence for both displaced and host community women, while cellphone access for displaced women was the second worst in the five-country sample. The forcibly displaced index reminds us of the need to go beyond national averages to better understand disparities in women’s status and opportunities.