Debunking the Fallacy of the Ideal Victim: Articulating the Mechanics of Coercion

Image by freelance photographer Richard Burdett

By Benjamin Thomas Greer and Ryann Jorban

Commercial sexual exploitation has proven to be conducted with ever-evolving criminal tactics. There are endless ways in which traffickers prey upon and exercise control over their victims. While the traditional approach of physical force to gain compliance in their victims, often involving the use of rape, beatings, and physical confinement, traffickers have found coercive methods to be more successful in maintaining compliance over their victims.

Both state and federal definitions of human trafficking include a critical, often underappreciated, aspect of this crime: coercion. Coercion is also measured as a psychologically based form of control, which may be exerted through threats of harm to the victim and his or her family or threats of deportation. It is important to note that this crime does not require physical force, physical bondage, or physical restraint. Uncovering, understanding, and conveying coercive compliance is much less intuitive and much more difficult to convey. Recent high-profile trafficking trials have highlighted the difficulty and the importance of articulating how coercion can play a role in a successful human trafficking prosecution.

In September of 2024, Sean Combs was indicted by a grand jury on three felony counts of: Racketeering Conspiracy; Sex Trafficking by Force, Fraud, or Coercion; and Transportation to Engage in Prostitution. Combs entered a plea of not guilty and was denied bail, with the court citing concerns for potential witness threats and intimidation. The defense claimed in its appeal for bail, among other things, that a 2016 surveillance video clip from a hotel hallway, in which the defendant can be seen kicking and dragging Cassie Ventura, is the product of “a ten-year loving relationship” that dissolved because of Ventura’s “jealousy over [the defendant’s] infidelity.” Bail was denied.

During the pendency of the trial, Combs’ former girlfriend testified that the defendant had subjected her to a decade of intense abuse, with her former stylist testifying he had witnessed the defendant being violent, adding that he and [Ventura] hid “too many times to count” to avoid being “attack[ed]” by Combs. Evidence submitted showed Combs forced Ventura to take ecstasy and ketamine, a method of subduing her. The judge warned the defense that the defendant may need to be removed from the court if he attempts again, as the Judge witnessed him, to make any facial expressions to jury members or attempt to have any interaction with or influence the jury.

At one point, defense counsel made statements, which, when examined with nuance, could both prove coercion and disprove it depending on an underlying comprehension of the complexity of intimate partner coercion: “For Cassie, she made a choice every single day for years. A choice to stay with him — a choice to fight for him,” she said. “Because for 11 years, that was the better choice. That was her preferred choice.” On July 2, 2025, after three days of deliberation, the jury found Combs not guilty of racketeering conspiracy and of sex trafficking charges involving Ventura and another, unidentified woman. He was found guilty on two counts of transportation for prostitution involving Ventura, another former girlfriend, and male sex workers.

Jurors did not seem to accept the concept of Ventura and “Jane” as absolute victims of Combs. Courtroom observers insinuated the jury’s lack of appreciation due to Ventura’s and “Jane’s” participation in and expression of excitement about his “freak-offs” or hotel nights. In court, prosecutors struggled to convince the jury that the women were coerced into their actions by Combs. Doubt over their testimony and the evidence presented, which did show gleeful texts to Combs, only hindered their ability to see the scenario as an example of coercive control, as presented by the prosecutors.

While we respect the findings of the jury, the complexities of this case highlight the need for the expanded use of experts to articulate and help the jury comprehend the psychological impact of varying types of coercive methods a trafficking victim may have endured.

Articulating Coercion is Exceedingly Difficult Due To Its Individualized Nature and Subjectivity

Coercion is a personal subjective feeling. Experienced differently by each individual, based on their life experiences and personal vulnerabilities. The methods used by a trafficker are specifically designed and honed to break the will and independent spirit of each one of their victims. A tactic successfully used against one victim may not have the desired effect on another. Where other areas of the law ask a jury to assess how the “reasonable person” may act, assessing coercion requires the finder of fact to” understand a reasonable victim” and essentially step “into the shoes” of a person for whom the juror most likely has no frame of reference. Indeed, if, during voir dire, the defense has been doing their job, the jurors will be devoid of anyone who has any real-world or professional insight into the reality and the reasonable actions of a victim of abuse and exploitation.

This metaphysical understanding of the reasonability of an action by someone whose experience is completely alien to yours is exceedingly difficult to achieve, as you are asked to leave your reality and adopt the reality of another. A prosecutor is tasked with creating this shift via a one-way conversation with the jury. After voir dire, the prosecutor is not allowed to ask the jury pointed and probing questions to ascertain the jurors’ state of mind. The prosecutor has spent months or years investigating the facts of the case. Learning and internalizing every small fact of the case through hundreds of hours of interviewing the victims and witnesses. Indeed, they have the experiential information provided to them by many victims, over many years, and may, in some cases, even have their own experiences to help them understand the “reasonable” reality for their victims. Their transformation has occurred over a much longer timeframe, with far more data points, than the jury will ever experience. To help shorten that timeline and increase the impact of the testimonial information for the jury, prosecutors need to find methods and tools to help the jury rapidly make this transformation.

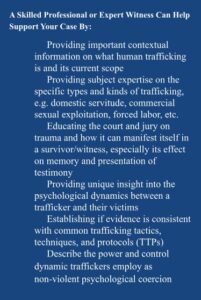

A Successful Human Trafficking Case May Require the Use of an Expert Witness

Human trafficking cases can be extremely complex, with intricate criminal, social, and emotional components, which are difficult to demonstrate in court. Many of the criminal actions conducted by traffickers and the abuse the victims endured require testimony from an expert or subject matter professional. Too often, victims sustain horrific physical and psychological abuse from their traffickers and exploitative consumers. They torture, defeat, starve, and fracture the lives of their victims. Prosecutors can utilize and are increasingly relying upon expert testimony to explain and corroborate the trafficker’s coercive tactics or to dispel commonly held stereotypes.

Generally, a witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise” if:

- The expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue,

- The testimony is based on sufficient facts or data,

- The testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods, and

- The expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case.

Additionally, “[a]n opinion is not objectionable just because it embraces an ultimate opinion.”

The need for expert testimony may vary from country to country, city to city, often depending on how informed the court is of the issue implicated in a trafficking case. Depending on the knowledge and sophistication of the Judge and Court itself, an expert might even be needed before a jury trial for a probable cause hearing or a motion to admit evidence

Working with experts to prepare and to help build commercial sexual exploitation trafficking cases, prosecutors are better situated to identify key evidence and more equipped to explain the context of the crime to the trier of fact. Expert testimony can be critical in helping prosecutors explain dynamics and victim behavior to the jury so that jurors will understand how the control tactics of an individual trafficker will affect the particular victim. This priming of a jury’s understanding will both assist the prosecutor in providing context for a victim’s reaction to the trafficker’s coercion and, in the likelihood of a non-cooperative witness, will help the jury in understanding that a victim’s recalcitrance should not be evidence of dishonesty.

situated to identify key evidence and more equipped to explain the context of the crime to the trier of fact. Expert testimony can be critical in helping prosecutors explain dynamics and victim behavior to the jury so that jurors will understand how the control tactics of an individual trafficker will affect the particular victim. This priming of a jury’s understanding will both assist the prosecutor in providing context for a victim’s reaction to the trafficker’s coercion and, in the likelihood of a non-cooperative witness, will help the jury in understanding that a victim’s recalcitrance should not be evidence of dishonesty.

No matter the quantity or quality of laws enacted by the legislature, “[w]hen the system is ineffective or indifferent to victims, the victims remain vulnerable, offenders are not held accountable, communities become less safe, and justice is not achieved.”

Implementing innovative prosecution and investigation techniques allows the system to operate effectively, which creates law-in-action and ensures justice for the children of the United States.

There are many elements of human trafficking that expert testimony can help demonstrate. In the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s Report, Evidential Issues in Trafficking in Persons Cases they highlight just a few areas where there is a need for expert testimony:

1 – Expert opinions can relate to medical matters

Medical experts can assist the court by presenting a medical opinion on the age of a victim; by documenting injuries or the victim’s psychiatric situation; or by giving a medical opinion on the question of whether a victim was subject to rape.

2 – Expert testimony in the field of psychology in general and victimology in particular

Expert testimony in the field of psychology in general and victimology in particular is viewed by some courts and some practitioners to be a particularly important source of evidence in trafficking in persons cases, because the victim’s personality and psychological state are often central to understanding the case. On the other hand, some practitioners are reluctant to use such “soft science” testimony.

3 – Testimony by an anthropological or cultural expert

Testimony of anthropological or cultural experts may be useful to explain certain phenomena, and, for example, the meaning of certain kinds of tattoos with a cultural meaning or the implications of “juju” (witchcraft) ceremonies on the behavior of victims and defendants in trafficking in persons cases. Furthermore, in certain cases, the motivation or lack of motivation of the victim to tell the full story can be explained, at least in part, by aspects of his or her culture.

Common human trafficking defenses, which may necessitate expert testimony to rebut:

- Limitations Period Defense

- Status of the Accused: Diplomatic Immunity Defense

- “No Force, Fraud, or Coercion” Defense

- Status of Alleged Victim: Family Member Defense

- Cultural Defense

- Immigration Status of Alleged Victim: Immigration “Fraud” Defense of Consent

- Defense Based on Perceived Age of Alleged Victim

- “Not Slavery” Defense

- Independent Contractor/Lack of Agency Defense Payment of Legal Wages Defense

Numerous state statutory constructions recognize and credit the value of expert testimony in trafficking cases. California Evidence Code section 1107.5 allows for the testimony of an expert witness who may provide testimony regarding the effects of human trafficking on human trafficking victims, including the nature and effect of physical, emotional, or mental abuse on the beliefs, perception, or behavior of human trafficking victims.

The dynamics of human trafficking and the effects on a victim, such as trauma bonding and remaining with an abuser, may be appropriate areas of expert testimony, as this subject is one that is normally beyond the common experience of a juror and requires that the juror understand the “reasonable victim” standard in trafficking. Expert testimony may also be needed to explain the use of common street terms such as “being in the life,” “the rules of the game,” “daddy,” or “a fresh or clean girl.”

Issues of homelessness, truancy, juvenile and adult criminal contacts, and a history of dependency system involvement may present special challenges for a jury handling a criminal trial with this type of witness. Minor trafficking victims, referred to as CSEC (commercially sexually exploited children), have often been subject to unfathomable physical and emotional abuse while being trafficked. They may be unwilling to participate in the court process, have a genuine fear of retribution from their trafficker, and may present as hostile and uncooperative witnesses.

Conclusion

Human traffickers are proven predators. As a predator, they hunt for a person highly susceptible to being used, controlled, or harmed. The most successful traffickers become extremely adept at understanding/exploiting their victims’ psychological pressure points, knowing which cultural or personal experiences they can prey upon to exact compliance.

Putting the victim first not only benefits the victim but also improves the chances of a successful prosecution. As many law enforcement officers have reported, trafficking victims are often unwilling to serve as witnesses for the prosecution. The reasons are many. They may distrust the government, be fearful of retaliation against themselves or their families, or be wary of placing themselves under legal scrutiny when they have participated in illegal acts (albeit by coercion). Psychologically groomed to tolerate unacceptable behavior, they may not fully understand that the perpetrators did something wrong. Or if they do understand that a wrong was done to them, they may wish to distance themselves from it and move on with their lives. The better law enforcement and the victim’s support system understand the type and quality of victimization a survivor has faced, the better-informed decisions they can hold the trafficker fully accountable for their crime.

Successfully applying a victim-centered approach to human trafficking investigations is extremely difficult, time-consuming, and resource-intensive. Why do we do it? Because when we place the victim in the center of the case and provide the fact finder with the context of the behavior, it works and, as importantly, it is the just thing to do.

Sources cited at the end of the post

Benjamin Thomas Greer, JD, MA – Mr. Greer’s role at the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services is as a subject matter expert in the field of human trafficking and child sexual exploitation, specifically instructing and developing human trafficking courses for law enforcement and emergency management personnel. His tasks include creating training courses for OES’s California Specialized Training Institute (CSTI) and researching the nexus between terrorist financing and human trafficking. Before joining OES, he served as a Special Deputy Attorney General for the California Department of Justice. There, he led a team of attorneys and non-attorneys in a comprehensive report for the California Attorney General entitled, “The State of Human Trafficking in California 2012.” Aside from his work with CalOES, he recently graduated from the Naval Postgraduate School’s Center for Homeland Defense and Security Master’s Degree Program and is a Research Associate for the University of Cambridge’s Centre for Applied Research in Human Trafficking.

subject matter expert in the field of human trafficking and child sexual exploitation, specifically instructing and developing human trafficking courses for law enforcement and emergency management personnel. His tasks include creating training courses for OES’s California Specialized Training Institute (CSTI) and researching the nexus between terrorist financing and human trafficking. Before joining OES, he served as a Special Deputy Attorney General for the California Department of Justice. There, he led a team of attorneys and non-attorneys in a comprehensive report for the California Attorney General entitled, “The State of Human Trafficking in California 2012.” Aside from his work with CalOES, he recently graduated from the Naval Postgraduate School’s Center for Homeland Defense and Security Master’s Degree Program and is a Research Associate for the University of Cambridge’s Centre for Applied Research in Human Trafficking.

Ryann Jorban joined the LA County District Attorney’s Office in 1998. Most of her career has been spent prosecuting violent crimes against the most vulnerable members of our society, including children, the elderly, people with physical and developmental disabilities, and individuals being abused by their significant others or family members.

In 2020, she was named the Deputy in Charge of the Economic Justice and Notario Fraud Unit of the Consumer Protection Division, where she pursues criminals who prey on our most vulnerable consumers, including the elderly, disabled, recent immigrants, and others who are frequent targets for consumer-related crimes.

In 2022, she founded the Labor Justice Unit, where she also serves as the Deputy in Charge. The Unit focuses on the systematic theft of wages and labor explo

itation of the most vulnerable workers in LA County through prosecution and collaboration with other organizations and agencies working in this area.

She is recognized as an expert in the prosecution of labor exploitation and criminal fraud exploitation of vulnerable communities and provides training and consultations on these issues across the state and nation. She also leads several statewide and nationwide working groups and task forces working in these two areas of expertise.

Sources:

- https://www.newyorker.com/culture/critics-notebook/the-tragedy-of-the-diddy-trial

- Tsioulcas, Anastasia (May 17, 2024). “Newly surfaced video shows apparent assault by Sean Combs like claims in settled case”. NPR. Retrieved June 2, 2025.

- Mutanda-Dougherty, Anoushka (May 28, 2025). “Cassie’s ex-stylist: We hid ‘too many times to count’ to stop Diddy ‘attack'”. BBC. Archived from the original on June 1, 2025. Retrieved June 1, 2025.

- del Valle, Lauren; Brown, Nicki; Levenson, Eric; Scannell, Kara (June 6, 2025). “Judge warns Sean Combs and accuser ‘Jane’ outlines sexual ‘hotel nights'”. CNN. Archived from the original on June 6, 2025. Retrieved June 6, 2025

- https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/15/arts/music/cassie-diddy-trial-combs-defense.html

- https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/sean-diddy-combs-verdict-analysis-rico-sex-trafficking-1236305166/#:~:text=Jurors%20also%20didn%27t%20seem,coercive%20control%2C%20as%20prosecutors%20do%20

- Hussein Sadruddin, Natalia Walter & Jose Hidalgo, Human Trafficking in the United States: Expanding Victim Protection Beyond Prosecution Witnesses, 16 STAN. L. & POL’Y REV 379, 383 (2005).

- Missouri sex slave case may hinge on expert view of subculture, available at https://kansascity.relaymedia.com/amp/latest-news/article311443/Missouri-sex-slave-case-may-hinge-on-expert-view-of-subculture.html.

- Sarah Warpinski, Know Your Victim: A Key to Prosecuting Human Trafficking Offenses (2013),

Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.msu.edu/king/222. - See People v. McAlpin (1991) 53 C3d 1289, 1302-1304, 283 CR 382, 389-390.

- Fed. R. Evid. 702.

- Fed. R. Evid. 704(a).

- Dupree, Tiffany, You Sell Molly, I’ll Sell Holly: Prosecuting Sex Trafficking in the United States, 78 La. L. Rev. 3, pp.1056-1057 (2017-2018).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Evidential Issues in Trafficking in Persons Cases, available at https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/2017/Case_Digest_Evidential_Issues_in_Trafficking.pdf.

- Am. Soc’y Int’l L., “Human Rights,” in Benchbook on International Law § III.E (Diane Marie Amann ed., 2014), available at www.asil.org/benchbook/humanrights.pdf.

- Doe v. Siddig, 810 F. Supp. 2d 127 (D.D.C. 2011).

- See Tabion v. Mufti, 73 F.3d 535 (4th Cir. 1996) [Only diplomats credentialed under the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations enjoy this total immunity. Consular officers and individuals working for international organizations have only functional immunity. See Park v. Shin, 313 F.3d 1138, 1143 (9th Cir. 2002) and Swarna v. Al-Awadi, 622 F.3d 123, 137-38 (2d Cir. 2010) (analyzing residual immunity provided for under Article 39(2) of the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations)].

- See, e.g., Doe v. Siddig, 810 F. Supp. 2d 127 (D.D.C. 2011), and United States v. Farrell, 563 F.3d 364 (8th Cir. 2009).

- See, e.g., Velez v. Sanchez, 693 F.3d 308, 328 (2d Cir. 2012); Mesfun v. Hagos, No. CV 03-02182 MMM (RNBx), 2005 WL 5956612 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 16, 2005).

- See, e.g., United States v. Afolabi, Crim. No. 2:07-cr-00785-002 (D.N.J. 2007)

- United States v. Paris, No. 3:06-cr-64, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 78418, at 29-30 (D. Conn. Oct. 23, 2007); See United States v. Martinez, 621 F.3d 101 (2d Cir. 2010), cert. denied, 131 S. Ct. 1622 (2011).

- United States v. Daniels, 653 F.3d 399, 409-10 (6th Cir. 2011)

- See, e.g., Swarna v. Al-Awadi, 622 F.3d 123 (2d Cir. 2010); United States v. Veerapol, 312 F.3d 1128, 1132 (9th Cir. 2002), cert. denied, 538 U.S. 981 (2003).

- See United States v. Farrell, 563 F.3d 364 (8th Cir. 2009).