Bangladeshi migrants working in Malaysia at the cost of debt, delay, and death

Migrant workers make up about one in five jobs in Malaysia, according to the US State Department. They work in shops, factories, plantations, and construction, helping produce major shares of the world’s palm oil and rubber gloves, and over $100 billion in electronics and semi-conductors annually. But despite being vital to Malaysia’s economy, many migrant workers face poor treatment and fear speaking out due to job loss and debt obligations. Bangladeshi workers, however, carry some of the heaviest debt burdens.

Over the past decade, more than 800,000 Bangladeshi workers have migrated to Malaysia. Many borrow large sums to pay recruitment fees for jobs that often fail to materialize. Investigators, labor analysts, and former government officials describe a recruitment system shaped by entrenched corruption, where excessive fees push workers into debt bondage and create conditions linked to forced labor and human trafficking.

“clearly a victim of human trafficking,”

Workers typically pay thousands of dollars before leaving Bangladesh, far more than migrants from other countries. Fees accrue at every stage—from local agents and medical checks to airfare and unofficial payments—leaving workers financially trapped before they arrive. If promised jobs fall through, workers find themselves in precarious situations. Unable to seek help without risking detention or deportation, many migrants are left waiting indefinitely or forced into undocumented work.

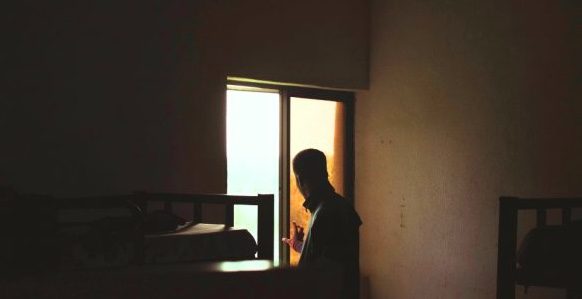

One such case involved Shofiqul Islam, a Bangladeshi farmworker who borrowed approximately $4,400 to secure a construction job in Malaysia. An amount that would be comparable to an American spending $140,000 for a job. After arriving, he never received employment. He remained in employer-arranged housing for months while his visa expired and interest on his debt increased. In February 2024, Shofiqul died while still waiting for work. Former Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission chief Latheefa Koya described him as “clearly a victim of human trafficking,” citing systemic failures embedded in the recruitment process.