What those TikTok videos about human-trafficking get wrong

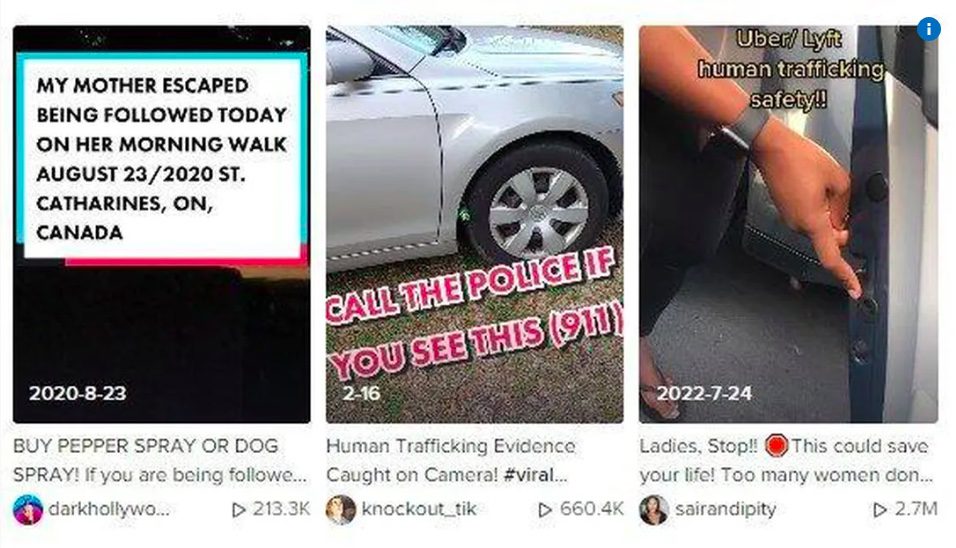

Videos circulating on TikTok might make you think the kidnappers are lurking behind every corner.

A new trend on the popular social-media platform has young people warning about human trafficking and how to avoid becoming a victim.

Some of the videos describe down-to-earth scenarios women face when out and about. For example, one TikTokker describes being followed in a store by a man wearing a hat, glasses and jacket, before confronting him and sending him on his way. She doesn’t say how she determined she was “almost a victim of human trafficking.”

Others are more outlandish, for example a video entitled “3 things human trafficers (sic) do to keep you outside of your car,” which has been shared more than 30,000 times. The video’s narrator describes tactics allegedly used by human-traffickers to catch a female target off guard, including hiding under their car with a knife to cut her Achilles heel to prevent escape, or placing honey on the hood of her car to distract her before emerging from the shadows and kidnapping her.

“I’m not really sure if they keep the jar on top, but if you just see honey on top of your car, or anything sticky, just enter your car and drive away,” the TikTokker warns. Yet another video describes a similar tactic, this time involving cash under windshield wipers.

The videos trending on TikTok, a platform on which about one in four users is under 20 years old, overemphasize stranger danger and the unlikely scenario of being kidnapped in public, says Janet Campbell, president and CEO of the Joy Smith Foundation, an organization focused on human-trafficking.

“I’ve seen a number of these different posts, which kind of set up a scenario of snatch-and-grab. And that’s not what human trafficking typically looks like in Canada,” Campbell said.

The videos risk misinforming people about what to look out for and creating a false understanding of how people actually fall victim to human trafficking, she added. Julia Drydyk, CEO of the Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking, said most of the cases they hear of involve someone who was known to the victim.

“I would say over 90 per cent of cases that we see through the Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline involve a trafficker that the victim knows and trusts and often loves,” Drydyk said.

“So the chances of someone being kidnapped off the street and forced into trafficking, while anything is possible, is really not the dominant trend that we are seeing.”

A common scenario, experts say, involves a person making a new friend or acquaintance, or getting involved in a romantic relationship. Typically, the trafficker will identify some kind of vulnerability, such as lack of money or a need for affection; they will then establish a relationship of trust, before separating the individual from their family and supports and ultimately coercing them into unwanted sexual activity for profit.

“The other myth that we often come across is this idea that people get rescued because they get spotted in a public washroom or some other scenario like that,” Campbell said. “More often than not, it’s a family member or friend who recognizes the signs.”

Some of the pushback against the trafficking-alert videos is taking place on TikTok itself. One video starts with a few seconds of a user recounting the windshield-wiper scenario, but it then quickly cuts to a different woman who describes herself as someone who has “had the privilege of actually getting to understand people’s stories.

“Human-trafficking does not look like some boogeyman … hiding out in the bushes of a parking lot looking to pounce on middle-class women through elaborate schemes with zipties and cash,” says the latter TikTokker.

Instead, it’s more likely to look like a person offering a vulnerable teen a couch to crash on, in exchange for sexual favours, or a dealer offering free drugs if the person will sleep with their friend.

Last month, the Joy Smith Foundation set up the website www.traffickingsigns.ca to raise awareness of real signs that someone may be getting sexually exploited, including having new clothing, jewelry or gifts without the money to pay for it, a sudden change in attire, or frequent sleepovers at a friend’s house.

Campbell said she didn’t want to downplay the seriousness of children being abducted in public, but it’s relatively rare compared to young people being groomed and exploited by someone they know.

An internal report by Drydyk’s centre found that transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals were being trafficked at a disproportional rate, with that group representing two per cent of calls despite forming 0.24 per cent of Canada’s population. It also found that the vast majority of victims and survivors were Canadian; only 14 per cent were foreign nationals. Yet she said some of the questions she hears the most is “Where are these people coming from? How are they getting across our borders?”

She said many Canadians still conflate human trafficking with human smuggling.

“Movies like ‘Taken’ are really making people think this happening to other people in other countries … or they’re being smuggled into Canada, where they’re experiencing forcible confinement and being chained to radiators,” Drydyk said.

“When in reality, human-trafficking looks far more like intimate-partner violence in Canada.”

The videos circulating online run the risk of reinforcing misperceptions and myths around human trafficking and misinforming people on what they should look out for, she added.

There was one trending TikTok video that Drydyk did praise — one of a man showing a woman a seemingly innocuous hotel room with clean towels stacked in a closet. In the video, he later learns it’s a major trigger for victims of human-trafficking and sexual exploitation.

“The reaction to the very clean hotel linens was actually probably the most rooted in the realities of what we’ve heard before,” Drydyk said. “If you haven’t experienced this type of trauma, if you see it, it won’t even make you think twice.”

Julie Kaye, an assistant professor at the University of Saskatchewan and author of “Responding to Human Trafficking,” said the type of alarm being expressed online is “almost expected,” based on where the majority of anti-trafficking funds have gone: Education and awareness, but also law enforcement.

“I think the challenge really is that these moral panics don’t translate into any type of effective supports for women or youth or children who are facing real vulnerabilities,” she said.

The videos feed into the narrative that villains are hiding in the shadows and that we need more police to catch them. Less attention and funding is spent on systemic issues that put women and girls in vulnerable positions — for example, inadequate access to housing or food and lack of transportation, Kaye said.

“Instead of talking about that, we are talking about quite sensationalized campaigns that do in turn reinforce policing, and particularly policing of those very vulnerable populations that end up becoming most at risk.”