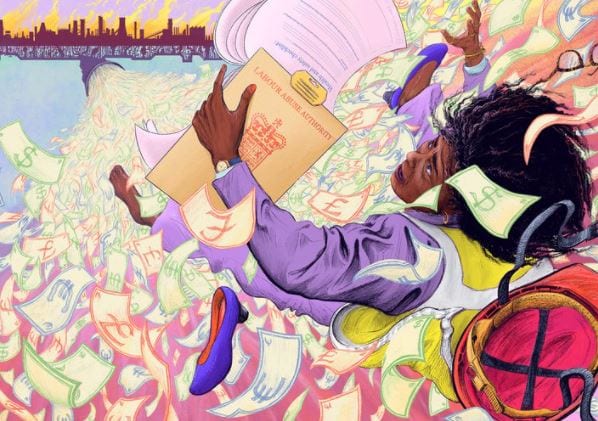

Private giving for anti-trafficking hides government inaction

When I began working on human trafficking more than two decades ago, the exploitation of human beings for private profit lay well outside mainstream public consciousness and concern. The laws were old and muddled, and the issue itself had no home or champion. This suited governments very well, not least because it effectively absolved them of legal and moral responsibility for practices that brought national economies significant, if often hidden benefit. And states were able to neatly sidestep charges of complicity by pointing to the fact that any ‘crimes’ were being committed by private parties. What could they do?

The Trafficking Protocol, adopted in December 2000, changed everything by clearly articulating the problem – and by affirming that governments do indeed have a legal responsibility to prevent trafficking, prosecute perpetrators and protect victims. Over the next 10 years the legal and political landscape around the issue changed dramatically. Under internal and external pressure, most countries introduced strong anti-trafficking laws modelled on new international and regional treaties. Prosecutions increased and, while victims continued to be routinely mistreated by public officials, there was at least some evidence that things were improving for some victims, in some situations. Perhaps most promising of all was the slowly emerging understanding that ‘trafficking’ is not, as originally presented, a rare and exotic criminal phenomenon confined to a handful of unfortunate countries. Rather, the exploitation that is the hallmark of trafficking is woven into the fabric of our lives. We are all complicit in a global economy that relies heavily on the exploitation of poor people’s labour to maintain growth, and on a global migration system that entrenches vulnerability.

Large-scale, private philanthropy began to muscle in on the anti-trafficking movement about a decade ago. This was well after much of the hard graft of developing legal and regulatory frameworks had been done, but right at the beginning of a ‘second wave’ marked by greater attention to structural causes and the need for complex, multidimensional responses. Throughout this time, I have watched the movement shift and change from the vantage point of an academic, opinion writer, lawyer, international civil servant and occasional combatant.

Click here to read full article.