n June, 2014, a man began digging into the soft red earth in the backyard of his house, on the outskirts of Kolwezi, a city in the southern Democratic Republic of the Congo. As the man later told neighbors, he had intended to create a pit for a new toilet. About eight feet into the soil, his shovel hit a slab of gray rock that was streaked with black and punctuated with what looked like blobs of bright-turquoise mold. He had struck a seam of heterogenite, an ore that can be refined into cobalt, one of the elements used in lithium-ion batteries. Among other things, cobalt keeps the batteries, which power everything from cell phones to electric cars, from catching fire. As global demand for lithium-ion batteries has grown, so has the price of cobalt. The man suspected that his discovery would make him wealthy—if he could get it out of the ground before others did.

Southern Congo sits atop an estimated 3.4 million metric tons of cobalt, almost half the world’s known supply. In recent decades, hundreds of thousands of Congolese have moved to the formerly remote area. Kolwezi now has more than half a million residents. Many Congolese have taken jobs at industrial mines in the region; others have become “artisanal diggers,” or creuseurs. Some creuseurs secure permits to work freelance at officially licensed pits, but many more sneak onto the sites at night or dig their own holes and tunnels, risking cave-ins and other dangers in pursuit of buried treasure.

The man took some samples to one of the mineral traders who had established themselves around Kolwezi. At the time, the road into the city was lined with corrugated-iron shacks, known as comptoirs, where traders bought cobalt or copper, which is also plentiful in the region. (In the rainy season, the earth occasionally turns green, as a result of the copper oxides beneath it.) Many of the traders were Chinese, Lebanese, and Indian expats, though a few Congolese had used their mining profits to set up shops.

One trader told the man that the cobalt ore he’d dug up was unusually pure. The man returned to his district, Kasulo, determined to keep his find secret. Many of Kasulo’s ten thousand residents were day laborers; Murray Hitzman, a former U.S. Geological Survey scientist who spent more than a decade travelling to southern Congo to consult on mining projects there, told me that residents were “milling about all the time,” hoping for word of fresh discoveries.

Hitzman, who teaches at University College Dublin, explained that the rich deposits of cobalt and copper in the area started life around eight hundred million years ago, on the bed of a shallow ancient sea. Over time, the sedimentary rocks were buried beneath rolling hills, and salty fluid containing metals seeped into the earth, mineralizing the rocks. Today, he said, the mineral deposits are “higgledy-piggledy folded, broken upside down, back-asswards, every imaginable geometry—and predicting the location of the next buried deposit is almost impossible.”

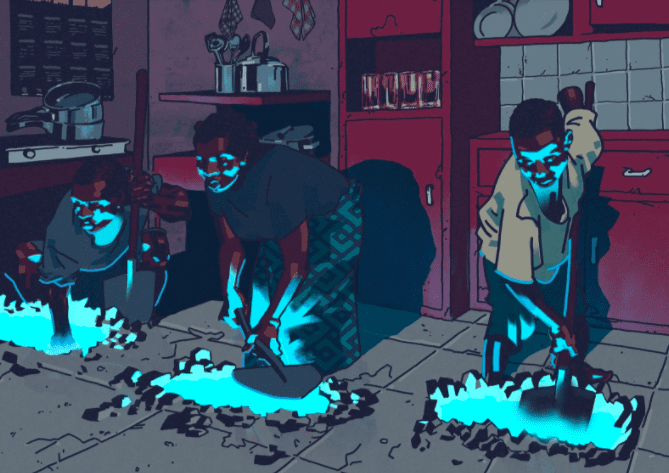

The man stopped digging in his yard. Instead, he cut through the floor of his house, which he was renting, and dug to about thirty feet, carting out ore at night. Zanga Muteba, a baker who then lived in Kasulo, told me, “All of us, at that time, we knew nothing.” But one evening he and some neighbors heard telltale clanging noises coming from the man’s house. Rushing inside, they discovered that the man had carved out a series of underground galleries, following the vein of cobalt as it meandered under his neighbors’ houses. When the man’s landlord got wind of these modifications, they had an argument, and the man fled. “He had already made a lot of money,” Muteba told me. Judging from the amount of ore the man had dug out, he had probably made more than ten thousand dollars—in Congo, a small fortune. According to the World Bank, in 2018 three-quarters of the country’s population lived on less than two dollars a day.

Hundreds of people in Kasulo “began digging in their own plots,” Muteba said. The mayor warned, “You’re going to destroy the neighborhood!” But, Muteba said, “it was complicated for people to accept the mayor’s request.” Muteba had a thriving bakery and didn’t have time to dig, but most locals were desperate. In Congo, more than eighty-five per cent of people work informally, in precarious jobs that pay little, and the cost of living is remarkably high: because the country’s infrastructure has been ravaged by decades of dictatorship, civil war, and corruption, there is little agriculture, and food and other basic goods are often imported. For many Kasulo residents, the prospect of a personal cobalt mine was worth any risk.

About a month after the man who discovered the cobalt vanished, the local municipality formally restricted digging for minerals in Kasulo. According to Muteba, residents implored the mayor: “We used to mine in the bush, in the forest. You stopped us. You gave all the city to big industrial companies. Now we discovered minerals in our own plots of land, which belonged to our ancestors. And now you want to stop us? No, that is not going to work.” Muteba recalled, “People started to throw rocks at the mayor, and the mayor ran away. And, when the mayor fled, the digging really started.”

Odilon Kajumba Kilanga is a creuseur who has worked in the Kolwezi area for fifteen years. He grew up in southern Congo’s largest city, Lubumbashi, which is near the Zambian border, and as a teen-ager he worked odd jobs, including selling tires by the roadside. One day when he was eighteen, a friend who had moved to Kolwezi called him and urged him to join a coöperative of creuseurs which roamed from mine to mine, sharing profits. “There were good sites that you could just turn up to and work,” Kajumba said, when we met in Kolwezi.

In those days, it took eight hours to get from Lubumbashi to Kolwezi by bus, on a rutted two-lane road. The thickets on either side of the highway crawled with outlaws, who occasionally hijacked vehicles using weapons they’d leased from impoverished soldiers. Once, bandits stopped a bus and ordered the passengers to strip; the hijackers took everything, even people’s underwear.

Kajumba knew that the journey to Kolwezi was dangerous, but he said of the creuseurs, “If they tell you to come, you come.” At first, the work, though strenuous, was exciting; he began each shift dreaming of riches. He had some stretches of good luck, but he never made the big score that would transform his life. Now in his mid-thirties, he is a laconic man who becomes animated only when he is discussing God or his favorite soccer team, TP Mazembe. Mining no longer holds romance for him; he sees the work as a symptom of his poverty rather than as a path out of it. When you are a creuseur, he said, you are “obliged to do what you can to make ends meet,” and this necessity trumps any fears about personal safety. “To be scared, you must first have means,” he said.

Kajumba joined the mining economy relatively late in life. In Kolwezi, children as young as three learn to pick out the purest ore from rock slabs. Soon enough, they are lugging ore for adult creuseurs. Teen-age boys often work perilous shifts navigating rickety shafts. Near large mines, the prostitution of women and young girls is pervasive. Other women wash raw mining material, which is often full of toxic metals and, in some cases, mildly radioactive. If a pregnant woman works with such heavy metals as cobalt, it can increase her chances of having a stillbirth or a child with birth defects. According to a recent study in The Lancet, women in southern Congo “had metal concentrations that are among the highest ever reported for pregnant women.” The study also found a strong link between fathers who worked with mining chemicals and fetal abnormalities in their children, noting that “paternal occupational mining exposure was the factor most strongly associated with birth defects.”

This year, cobalt prices have jumped some forty per cent, to more than twenty dollars a pound. The lure of mineral riches in a country as poor as Congo provides irresistible temptation for politicians and officials to steal and cheat. Soldiers who have been posted to Kolwezi during periods of unrest have been known to lay down their Kalashnikovs at night and enter the mines. At a meeting of investors in 2019, Simon Tuma Waku, then the president of the Chamber of Mines in Congo, used the language of a gold rush: “Cobalt—it makes you dream.”

After Kasulo’s mayor fled, many residents began tearing away at the ground beneath them. Some wealthier locals hired creuseurs to dig under their houses, with an agreement to split the profits. Two teams of creuseurs could each work twelve-hour shifts, chipping at the rock with hammers and chisels. A pastor and his congregation began digging under their church, stopping only for Sunday services.

By the end of 2014, two thousand creuseurs were working in the neighborhood, with little regulation. Kajumba and his coöperative soon joined in the hunt for minerals. One man on Kajumba’s team, Yannick Mputu, remembers this period as “the good times.” He told me, “There was a lot of money, and everybody was able to make some. The minerals were close to the surface, and they could be mined without digging deep holes.”

But the conditions quickly became dangerous. Not long after the mayor formally prohibited excavating for minerals, a mine shaft collapsed, killing five miners. Still, people kept digging, and by the time researchers for Amnesty International visited, less than a year after the discovery of cobalt in Kasulo, some of the holes made by creuseurs were a hundred feet deep. Once diggers reached seams of ore, they followed the mineral through the soil, often without building supports for their tunnels. As Murray Hitzman, the former U.S.G.S. scientist, pointed out, the heterogenite closest to the surface often contains the least cobalt, because of weathering. Creuseurs in Kasulo were risking their lives to obtain some of the worst ore.

One of Kajumba’s teammates told me that their coöperative of six used to regularly extract two tons of raw material from a single pit in Kasulo. But most of the best sites were quickly excavated, and the yield from newer pits was less than half as much. The team was also ripped off by unscrupulous traders and corrupt officials. Kajumba said that lately he has struggled to pay his rent of twenty-five dollars a month. “Whenever we dig up a few tons, I send some money to my family,” he added.