Predators on the Network

Researcher says it’s time to study, then stop, child sex trafficking in higher education. Her new paper showing that predators skew white, male and academic is a start.

Following the 2015 arrest of the University of North Dakota’s then chair of family and community medicine, Robert Beattie, on child pornography charges, the Dakota Student newspaper ran an opinion piece asking, “We can’t help but wonder if this type of thing is common in other schools around the nation?”

Lori Handrahan, an independent scholar of gender-based violence in conflict zones, wondered the same thing. She’d already been researching child sex crimes involving military personnel and other classes of workers, so she started studying abuse perpetrated by college and university employees, too. Of particular interest to her was child sexual exploitation material (CSEM), otherwise known as child pornography.

Handrahan previously shared some of her initial findings on sex trafficking in higher education on Medium. But her new article in the Journal of Human Trafficking, and corresponding database, is the most complete picture of sex offenses against children in higher education published anywhere, ever.

It’s also one of the only projects to ever broach the subject.

As Handrahan’s study says, “Despite growing awareness of the crime, research on child sexual exploitation material is surprisingly scant with a near-total absence of perpetrator data.” That’s perpetrators generally, not just perpetrators in academe.

Yet there are reasons that colleges and universities should be particularly interested in this kind of data. While the federal Clery Act requires reporting on sex offenses on colleges campuses, for example, Handrahan says, CSEM crimes are not included. (Handrahan notes that insurance companies require detailed information on how institutions handle reports of child sex abuse, but that that information isn’t publicly available.)

While Handrahan’s data are carefully collected, verified and—for the aforementioned reasons—relatively robust, she warns they represent just a “dip analysis” of who in higher education is perpetrating what sex crimes against children, how they are doing so, and how their institutions respond. That’s because, in the absence of any other database, she had to rely mostly on published news reports, new releases from law enforcement and institutions, and relevant primary records (which sometimes had to be obtained via formal requests under open records laws).

Still, she says, a kind of profile of perpetrators, crimes and institutional responses emerges—one that may help inform policy decisions within institutions and beyond.

Findings

Of the 223 investigations, arrests and prosecutions that Handrahan identified and analyzed, CSEM offenders working in higher education were overwhelmingly white, male and on the faculty. Over half were in leadership positions, and they frequently used campus facilities or property to commit their crimes. More specifically: of all college and university faculty and staff members investigated, arrested or prosecuted, some 91 percent were white, 98 percent were male, 54 percent held leadership positions and 30 percent had received institutional awards for professional excellence.

Faculty arrests comprised the majority of Handrahan’s data, with these professors concentrated in the humanities and medical sciences and senior administrative roles. Concerningly, information technology and campus security or police personnel were common among staff arrests. Many of these arrestees had had access to especially vulnerable children via their jobs.

Although higher education has been known to have “pass-the-trash” or “pass-the-harasser” problem when it comes to sexual harassment, the CSEM offenders in Handrahan’s study weren’t generally new hires. Most employees had been at their institutions for more than 10 years at the time of their arrest.

At least 35 percent of the whole sample were parents, namely fathers.

Some 88 percent of the arrests and prosecutions Handrahan examined were fully adjudicated, with 75 percent of the offenders entering plea deals and 93 percent pleading guilty. The average jail sentence was 12 years, and average time to probation was seven years. Fines and victim restitution were relatively rare.

Critical to college and university security policies, 27 percent of these offenders were arrested or caught on campus. Forty-two percent used institutional property (think computers) to commit their crimes.

Handrahan—who delved deep into criminal complaints and other legal documents to understand just what these crimes entailed—said in an interview that headlines tend to downplay what the offenders in her database actually did. She cited the case of Christopher DeZutter, a former lecturer of chemistry at the University of Minnesota at Rochester, who was sentenced last year to a second stint in prison for what has been widely reported as possession of child pornography. But his criminal complaint reveals that he was in possession of “hard core,” sadomasochistic material involving the torture of preteen children, including infants and toddlers. And he used university property to watch it.

Beyond CSEM, some in the database were charged with or found guilty of child rape or molestation. One such person, Brent Martin, who pleaded guilty to child sexual assault in 2020, was the assistant director of the on-campus daycare at Butler Community College in Kansas.

Over all, 54 percent of the crimes Handrahan studied involved children 10 or younger in age, including infants and toddlers, with at least 130 reports of “hard core,” bestiality or sadomasochistic violent material involving preteens.

Sixty-four percent of the investigations, arrests or prosecutions were at public colleges or universities. Among private colleges implicated, 55 were religiously affiliated.

There were no known arrests at Hispanic-serving institutions, historically Black colleges and universities, or tribal campuses. Most of the colleges and universities mentioned had more than one known offender.

How Institutions Do and Should Respond

Handrahan says that institutions follow a two-pronged approach to apparent CSEM crimes involving their workers: respond in some manner just prior to or after an arrest, and then again upon indictment, guilty plea or sentencing. The most common response upon arrest or investigation was to put the employee on leave (paid or unpaid). Sometimes the accused resigned around the time of their arrest, and 13 percent of the time institutions fired them. Some 20 percent of institutions fired a worker after an indictment, guilty plea or sentencing. Most institutions made public statements at some point.

The study highlights what it describes as appropriate, “best” practices for institutions, such as North Dakota’s partnering with the Internet Watch Foundation to block CSEM access on campus after three employees—including that family medicine chair—were arrested on child pornography charges. It also says that Allegheny College was right to practice “transparency” and offer grief counseling when Kirk Nesset, then a professor of English there, was arrested on CSEM charges in 2014. (Nesset resigned a day after his arrest.)

In general, however, Handrahan says her results “documented largely inadequate responses to preventing/responding to child sex trafficking crimes by employees with a bias toward protecting perpetrators when these crimes emerge.” Moreover, “higher education institutions, public and private, do not appear to have widespread or well-established best practice standards for preventing/responding to CSEM crimes by employees.”

Handrahan urges higher education to do more to prevent CSEM and other crimes against children, arguing that “tertiary education is a high-status profession offering unique power to influence public policy through research agendas,” and, sometimes, access to vulnerable children.

The study notes, for instance, that the late Robert Herman-Smith, an assistant professor of social work at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte who was indicted in 2018 on five CSEM charges, had been the coordinator of a public child welfare program, and he researched early childhood intervention for at-risk children due to trauma, maltreatment and poverty. Donald Ratcliff, a professor of Christian education specializing in child psychology at Wheaton College in Illinois, was sentenced in 2014 to three years in jail on a CSEM guilty plea; he’d been trading material on the rape of children as young as 3 years old and reportedly claimed that his crimes were “moral” because “research in Europe” proved CSEM prevented people from becoming pedophiles.

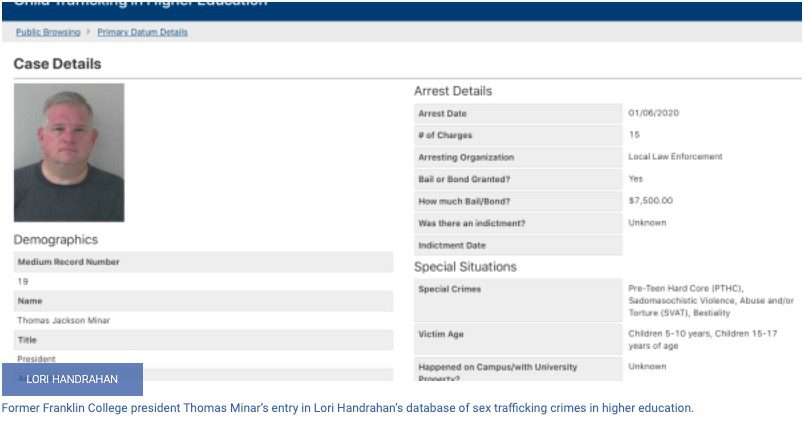

In a more recent case, Thomas Minar, then the president of Franklin College, was caught trying to meet up with a supposed 15-year-old whom he’d already been talking about sex with online, in 2020. He told the arresting police officer that he was a “distinguished person” who worked in higher education, according the criminal complaint against him—a strange response, but one that may shed some light on how predators (excluding Minar, who has since been found guilty) may benefit from their positions in academe. (Minar was also charged with possession of violent CSEM involving children under 10.)

Handrahan notes that she had to rely on private tips for certain cases in her database, as some offenders or institutions work to suppress public information about CSEM crimes.

Considering all these dynamics, the study recommends specific policy changes and directions for future research, including “scoping” the crime by studying college and university email addresses associated with CSEM forums; establishing some kind of national “predator” database of CSEM arrests and prosecutions; requiring verified criminal background checks as a prequalification for federal funding; and amending the Clery Act to include reporting of CSEM offenses.

Handrahan urges academe to continue to ask hard questions about the “white patriarchy of higher education,” including how it may reinforce patterns of abuse, and how CSEM crime patterns may be related to other forms of abuse. She further asks higher education to think of the “costs” of employing predators, from loss of academic prestige and tuition dollars after scandals, to lawsuits, lengthy criminal defenses, paid leave of up to two years for arrested employees, loss of funding and even providing full retirement benefits to convicted perpetrators.

“Our collective failure, as a country and within the higher education profession, to understand and stop child predators is a result, in part, of limited predator data,” Handrahan says. “Two hundred and twenty-three cases detailed in this research should prompt urgent action in the U.S. higher education sector and among policy makers concerned with protecting children and stopping child sex trafficking in all its forms—including CSEM possession, production and distribution.”