Pandemic impedes human trafficking policy development

The pandemic has affected nearly every aspect of life with border closures, lockdowns and quarantine measures, exacerbating the problem of people trafficking around the world today. From basic social services to more complex policing mechanisms, the pandemic has interrupted response networks for human trafficking and made people more vulnerable to this crime.

Most countries saw an overall decrease in crime, but the covert nature of human trafficking pushed networks underground as traffickers preyed on inequalities worsened by the pandemic. Termed ‘the shadow pandemic’, hidden by high-profile coverage of skyrocketing increases in gender-based violence, trafficking has received less attention because of the longer-term nature of the crime. Unlike domestic violence and other acute types of gender-based violence that are more immediate, we often don’t see the repercussions of trafficking for months and sometimes even years.

30 July is World Day against Trafficking in Persons which calls on governments worldwide to take coordinated and consistent measures to defeat this scourge. But more than 20 years after the adoption of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, governments are only marginally closer to adopting and implementing effective human trafficking policy and the pandemic has made the situation more dire. Diffusing Human Trafficking Policy in Eurasia focuses on this government response and evaluates the scope and breadth of policies in one region of the world known for human trafficking. The pandemic has also affected the adoption of new legislation to combat human trafficking as governments are preoccupied with other more pressing matters.

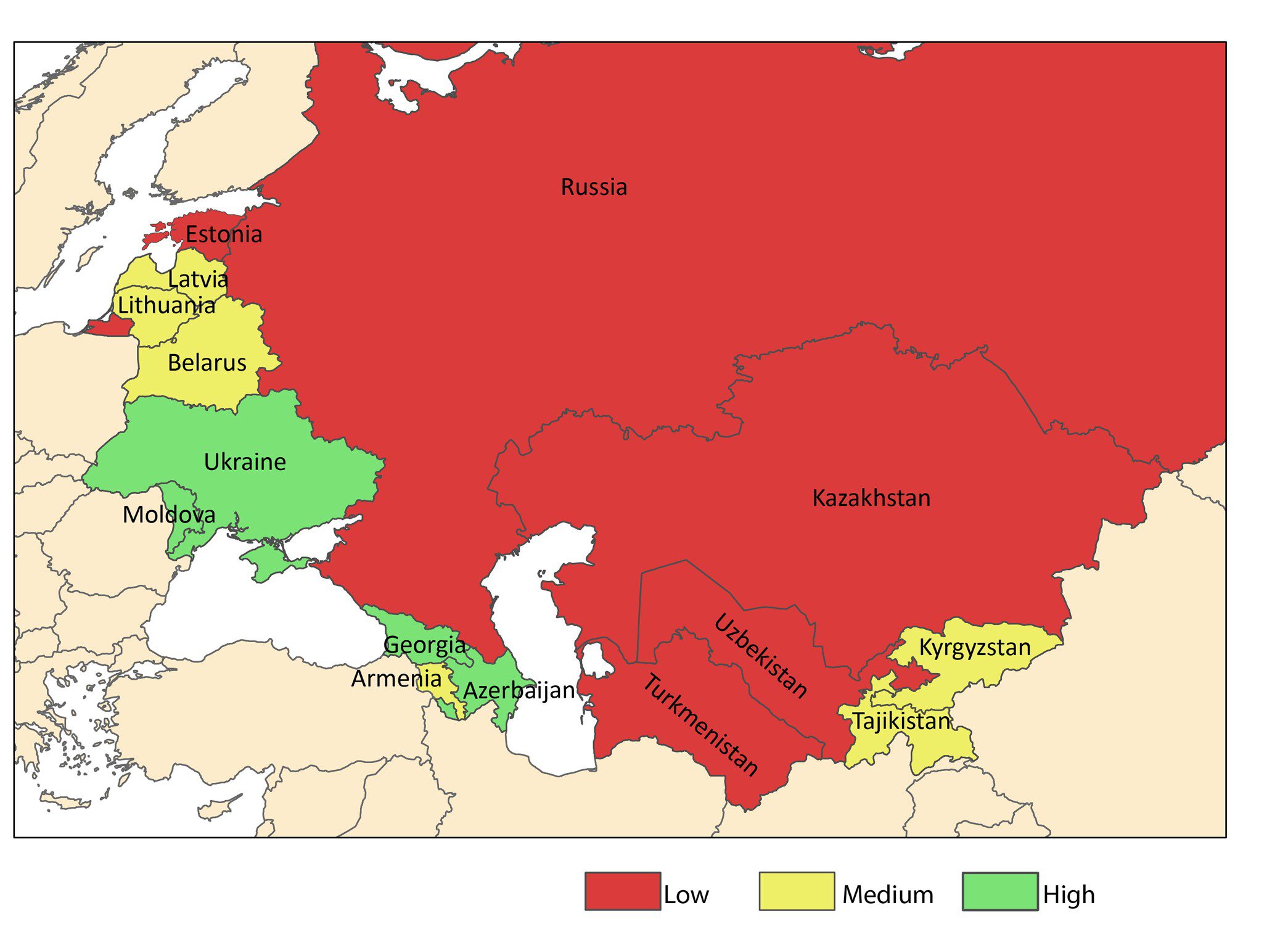

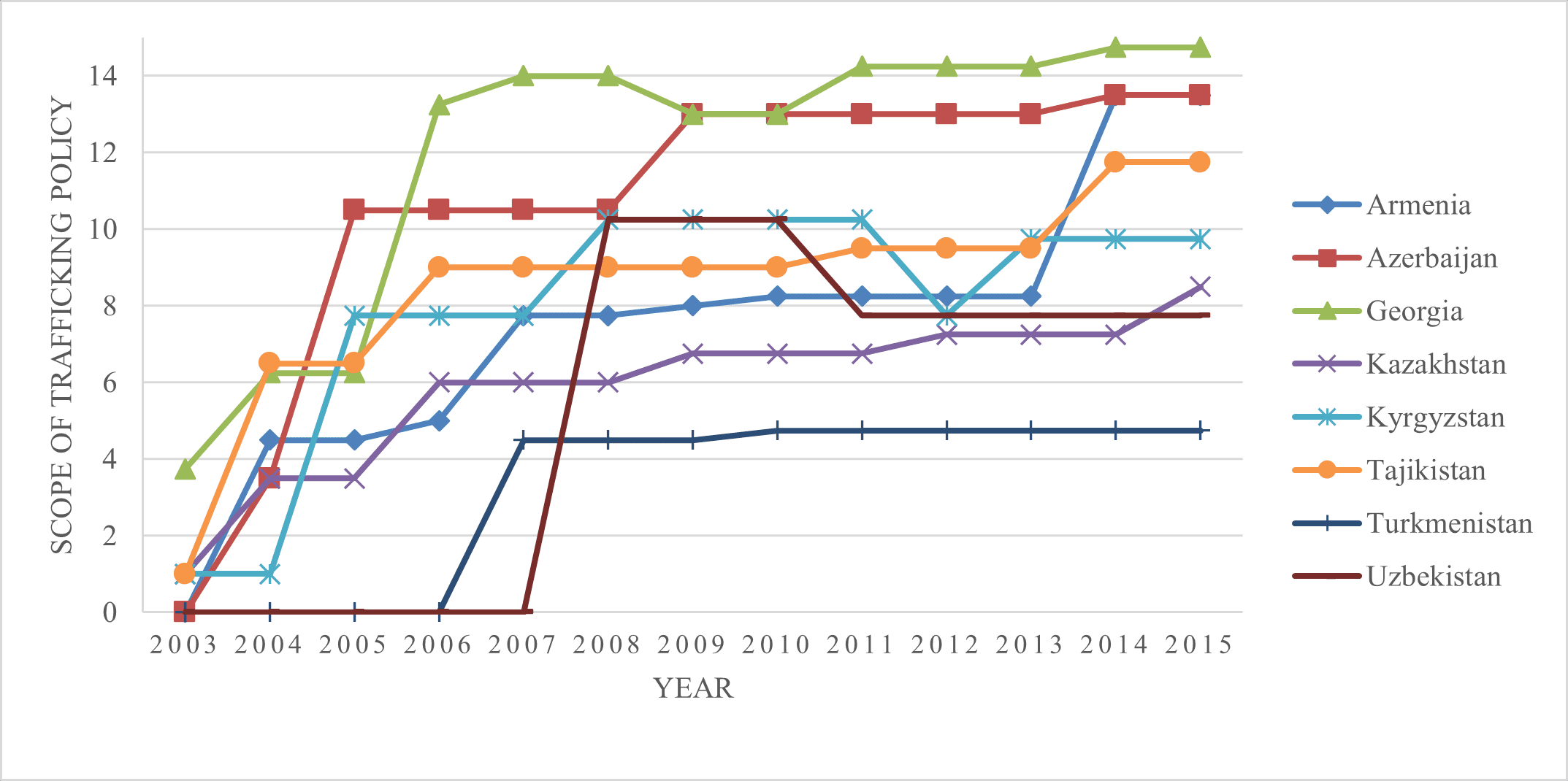

In order to measure policy change over time, I created the Human Trafficking Policy Index (HTPI) which is easily adapted to examine these policies in a global context. The HTPI was adapted from rankings and report cards used to measure the effectiveness of human trafficking policy and rank human trafficking policy in the US. Instead of using these secondary sources which rank other countries based on data and unclear methodology, I argue that policy documents and their content should be examined first hand to determine the scope of trafficking policies. I conducted a content analysis of the human trafficking policies in all 15 countries of Eurasia and constructed an index to measure the scope of human trafficking laws in the international context from zero to 15. This map shows the variation of policies on human trafficking in Eurasia.

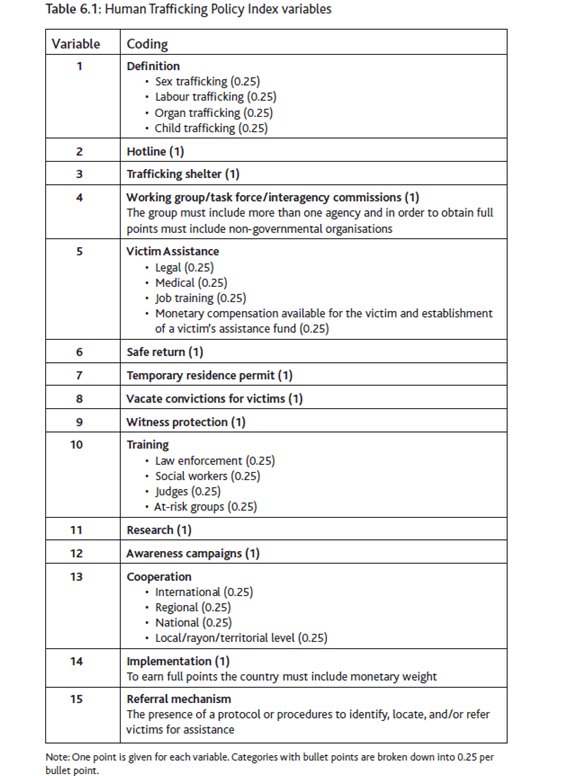

The scoring for the Human Trafficking Policy Index is outlined in Table 6.1. Countries were given one point for each component on the index they possessed and scored for each year the country had that specific policy element prescribed by law from 2003 to 2015. The first measure on the index evaluates each country’s definition of human trafficking including sex trafficking, labour trafficking, organ trafficking, and special provisions for child trafficking. If a country was missing one of these key parts of the provisions, they were scored 0.25 lower for that year. Next, countries were given one point for prescribing a human trafficking working group or task force into law, providing assistance to victims in legal, medical, shelter and monetary support. These types of services were significantly impeded during the pandemic but if a government had them prescribed in law, they were more likely to continue providing online and socially distanced services rather than removing them altogether. Training for social workers, judges and at-risk groups was another point on the index that was impacted by the pandemic as trainings on trafficking ceased and organisations went into survival mode providing only the most basic services. Outlining research and data collection, cooperation, implementation and referral mechanisms were also important components of encompassing human rights-based trafficking policy.

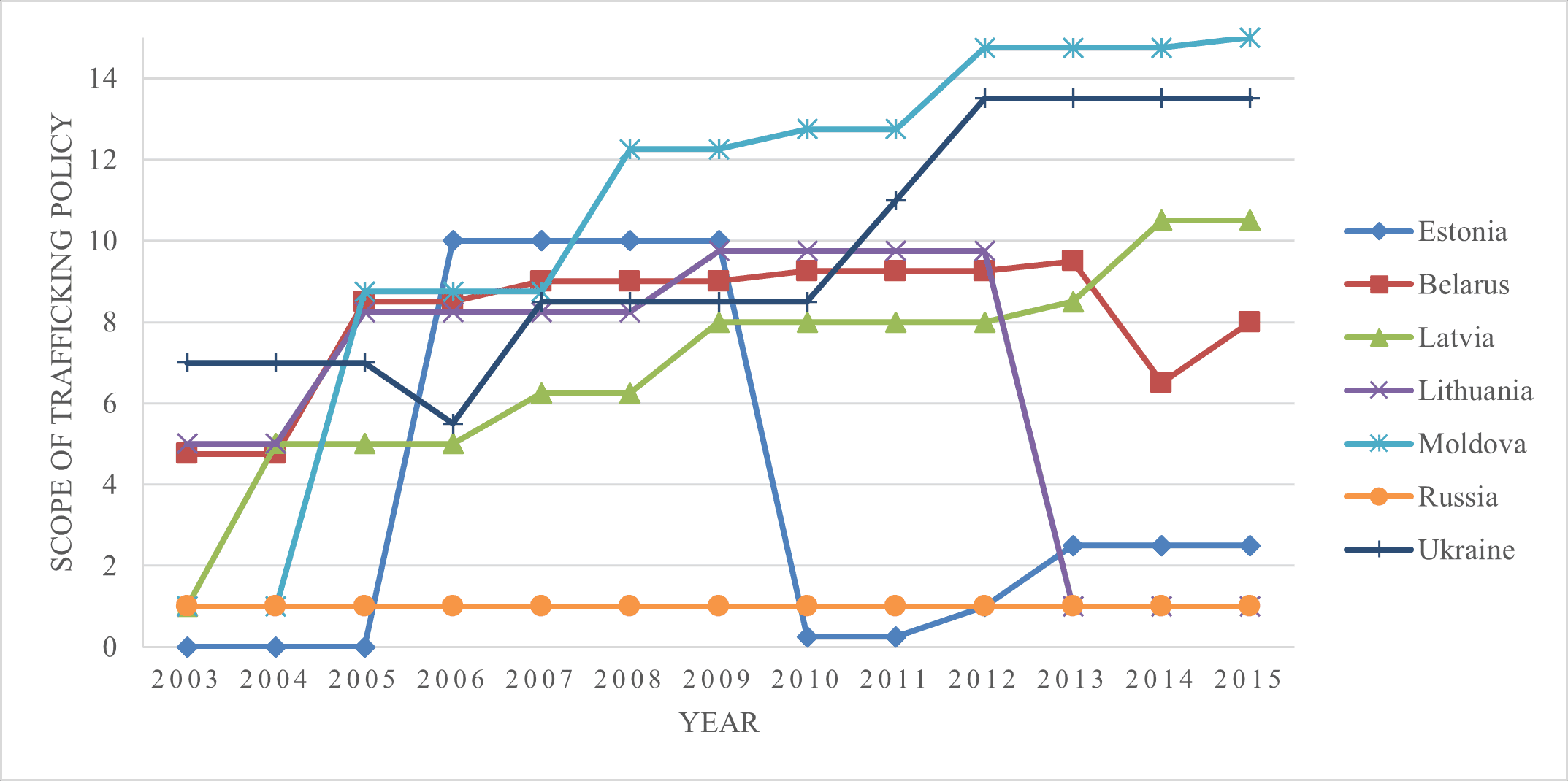

Figures 6.1 and 6.2 chart the development of human trafficking policy, demonstrating differences in Eurasia over time divided into Eastern Europe and the Caucasus and Central Asia. These figures reveal the significant variation of human trafficking policy in Eurasia among the 15 different countries. They demonstrate how some countries such as Moldova and Georgia are leaders in the region with their scope of human trafficking policy while others like Russia are lagging behind. Significant jumps for many countries such as Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan are evident in 2004 and 2007. Declines in 2010 and 2013 in some countries such as Estonia and Lithuania are also evident as policies lapsed and human trafficking was no longer a government priority. These findings are contrary to previous research that suggests that democratic countries are more likely to implement prevention and victim protection approaches than less democratic countries, as many non-democratic countries in the region (Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Armenia) are near the top of the rankings on the index.

Figure 6.1 Human Trafficking Policy Index in Eastern Europe

Examining different points across the Human Trafficking Policy Index reveals that most countries had encompassing definitions, working groups, assistance for victims, safe return, awareness campaigns and research within existing legislation. However, the points on the index that many struggled with were lack of implementation mechanisms, training for judges, vacating convictions for victims, residence permits, referral mechanisms and witness protection.

Figure 6.2 Human Trafficking Policy Index in the Caucasus and Central Asia

The results demonstrate the importance of looking beyond just criminalisation statutes in human trafficking policy research and including other types of trafficking policies. Trafficking policies have continued to improve over the years across much of the region but preliminary observations show that this legislative development was stalled by the pandemic. Now that governments are resuming legislative work, they must continue to develop trafficking policy and not leave survivors behind. As we emerge from the pandemic, inequalities will intensify human trafficking so governments must work to lessen the underlying conditions such as poverty, abuse and displacement that cause human trafficking. The HTPI offers policy makers a guide on different mechanisms and components for more effective and coordinated trafficking policies that can help victims of trafficking in the post-pandemic future.

Laura A. Dean is Assistant Professor of political science and director of the Human Trafficking Research Lab at Millikin University.

Diffusing Human Trafficking Policy in Eurasia by Laura Dean available on the Policy Press website. Order here for £60.00.

Diffusing Human Trafficking Policy in Eurasia by Laura Dean available on the Policy Press website. Order here for £60.00.

Bristol University Press newsletter subscribers receive a 35% discount – sign up here.

Follow Transforming Society so we can let you know when new articles publish.

The views and opinions expressed on this blog site are solely those of the original blog post authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Policy Press and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Image credit: Majestic Lukas on Unsplash