Hidden Away: Abuses Against Migrant Domestic Workers in the UK

Summary

In London they just locked me at home.… I ate after they finished, the leftovers…. When I ran away I was sleeping in the park because I didn’t know anybody here…. I felt like a beggar. —Sarah S., a Filipina domestic worker on a new tied visa, London, December 18, 2013.

Working and often living in other people’s homes, migrant domestic workers are among the most vulnerable workers, at risk of abuse and exploitation that often happens behind closed doors, making it difficult for them to seek help, and for people on the outside to see what is happening.

Every year, around 15,000 migrant domestic workers, many of them women from Asia and Africa, travel to the UK with their employers to look after their children, care for their elderly parents, clean their houses, and cook for them.

This report documents the abuses and exploitation faced by these migrant domestic workers who travel to the UK with their employers and the challenges they can experience when seeking redress. This report does not, however, address issues faced by migrant domestic workers who arrived in the UK by other means, for instance as asylum seekers, spouses or who are European Economic Area nationals.

While the category of domestic workers in private households as defined by the Home Office also includes drivers and gardeners, the domestic workers interviewed for this report worked inside their employers’ homes as cleaners, nannies, cooks, and/or cared for their employer or a member of their employers’ family.

The report also sets out relevant domestic, European, and international law, which is supposed to safeguard the rights of migrant domestic workers in the UK.

The report finds that some employers subject domestic workers to abusive living and working conditions, including forced labour. Safeguards are inadequate to prevent abuses; to allow those who are abused to escape and find protection; or to hold those responsible to account.

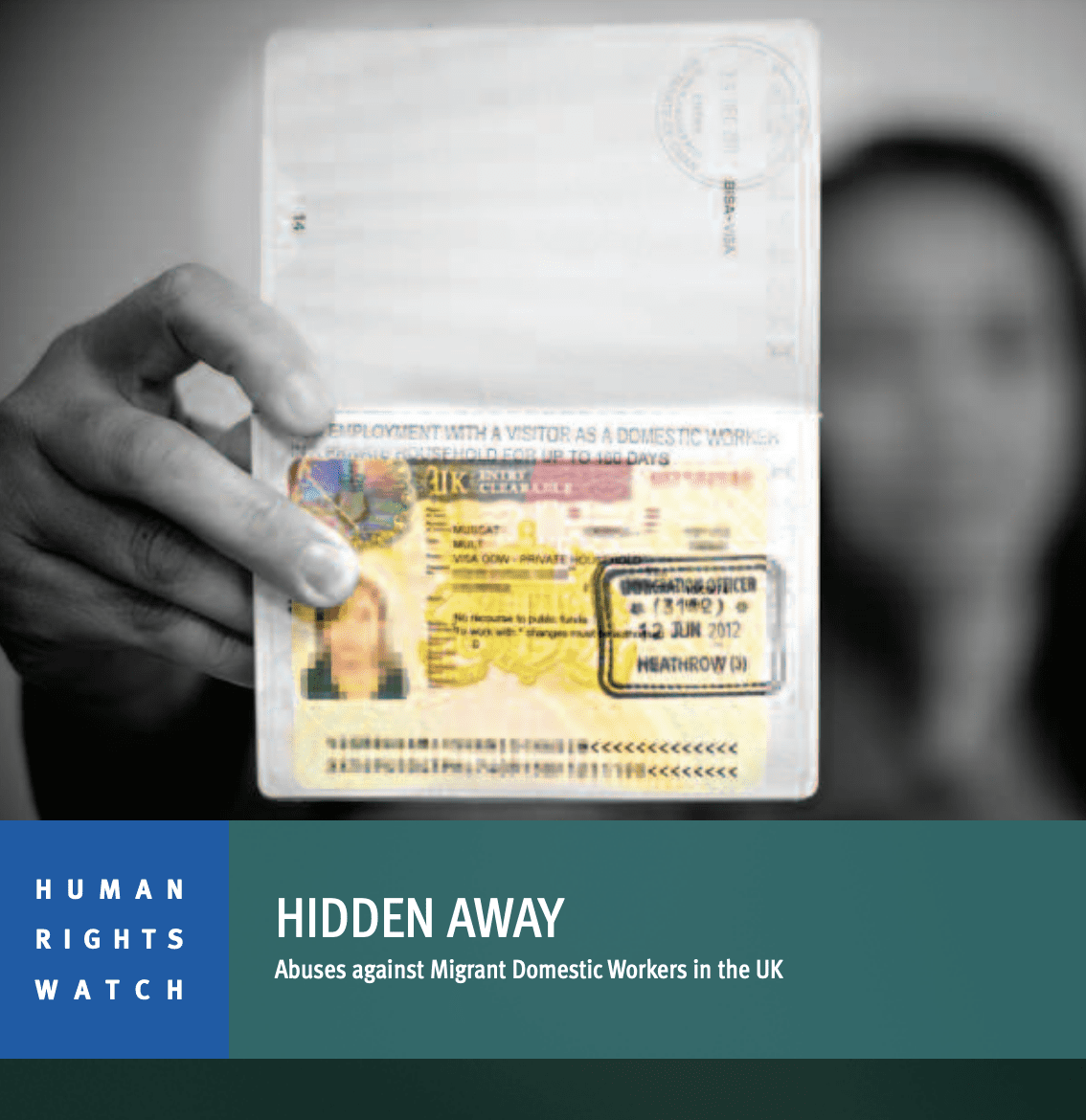

The report also describes how two developments since April 2012 have undermined the British government’s obligations under national, international, and European human rights law to protect migrant domestic workers from employer abuse and provide them with ways to access justice. The first development is a new “tied visa” that eliminates migrant domestic workers’ right to change employer and find other full-time work—often the most feasible way to escape abusive situations; the second development is budget cuts that have limited the ability of migrant domestic workers to seek help, including from employment tribunals.

Under the old (pre-April 2012) visa regime, the charity Kalayaan (the main organization providing assistance to migrant domestic workers in the UK), self-help groups, or other domestic workers were able to provide some assistance to abused workers who sought help because workers did not lose their immigration status by escaping from their employer and they could continue to work legally in the UK, if they found another job. Under the current system, however, there is little that charities and support groups can do for migrant domestic workers unless they are the victims of trafficking and are ready to go through the National Referral Mechanism (established to support victims of trafficking) system once they have escaped from their employer.

Experience from the UK and other countries indicates that the ability to change employers is one of the most practical and efficient ways for domestic workers to escape abusive situations.

Migrant domestic workers who work for diplomats are a particularly vulnerable group because their employers’ diplomatic immunity means they are not subject to national legislation. Before the visa changes, migrant domestic workers working for a diplomat could work for another diplomat in the same mission. Now they can only work for one diplomat and must leave the UK before their employer, or at the same time.

In June 2011, the UK was one of only nine states that did not vote in favor of the International Labour Organization’s Domestic Workers Convention—a groundbreaking international treaty that went into force in September 2013 and recognizes domestic workers’ rights to the same labour protections as other workers. The UK partly justified its decision by saying domestic legal protections are sufficient. At that time, migrant domestic workers had the right to change employer, a key protection for them to escape from abusive employers. But even though it removed that right in April 2012, at its Universal Periodic Review at the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council in September 2012, the UK rejected recommendations by other states to ratify the Domestic Workers Convention. The UK government claims that safeguards are in place to ensure migrant domestic workers are not abused by their employers. These include requiring that a worker has been with their employer for at least a year before going to the UK, and requiring that both employee and employer sign a declaration of the terms and conditions of their UK employment, theoretically preventing abusive relationships being imported to the UK.

This report shows that these protections are not adequate given migrant domestic workers’ lack of mobility and rights, particularly since the new tied visa was introduced. For example, some workers said their employer told them to sign a document with false information about their salary, time off, and working hours.

Read more here.