“Everywhere is Trouble:” An Update on the Situation of Rohingya Refugees in Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia

In May 2015, human trafficking syndicates abandoned boats of thousands of Rohingya refugees and Bangladeshi nationals coming from Myanmar’s Rakhine State and Bangladesh, leaving them adrift in the Andaman Sea. Instead of initiating search and rescue efforts, key countries in the region reinforced their borders and some intercepted and towed stranded boats farther out to sea. Following international outcry, some member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agreed to allow disembarkation and provide temporary shelter to survivors. The failure of ASEAN to immediately prioritize the protection of survivors led to an unknown loss of life at sea.

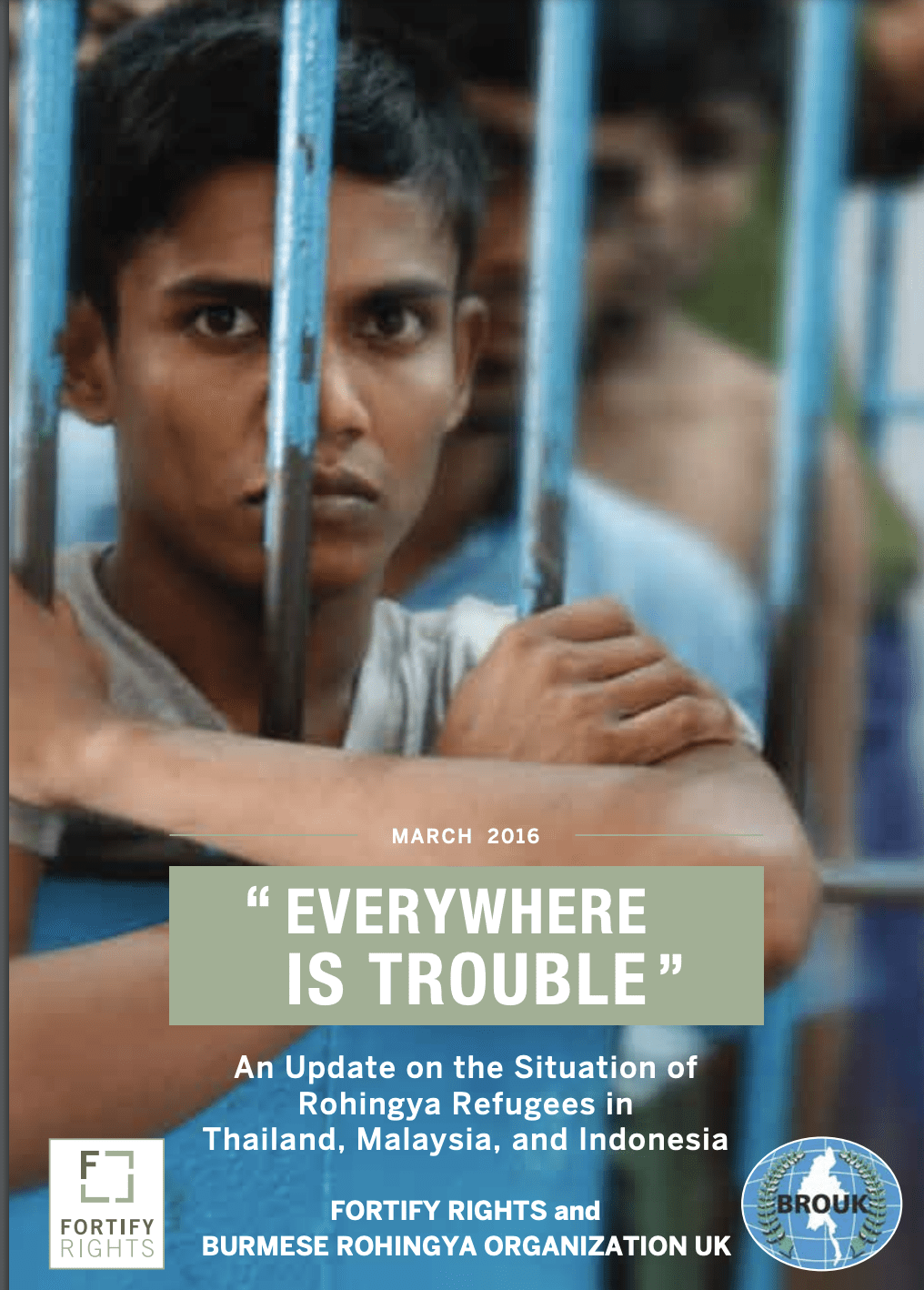

Almost ten months later, the Burmese Rohingya Organization UK (BROUK) and Fortify Rights traveled to Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia from February 15 to March 9 to assess the situation of Rohingya refugees in each country. Representatives from the organizations met with government officials, United Nations officials, and nongovernmental organizations; visited immigration detention facilities, government-operated shelters, and refugee camps; and conducted interviews with Rohingya refugees and survivors of human trafficking.

This briefing is based on those meetings and interviews.

Rohingya refugees continue to lack access to basic protections in Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. As a result, thousands of Rohingya refugees in Southeast Asia are subject to abuse, exploitation, human trafficking, protracted and indefinite detention, and refoulement.

In Thailand, BROUK and Fortify Rights are gravely concerned about the protracted detention of hundreds of Rohingya refugees in Immigration Detention Centers (IDCs) and government-run shelters. For instance, Thailand has detained at least 40 Rohingya refugees for approximately ten months at the Songkhla IDC, including reportedly a dozen or more boys under the age of 18. All of the children in the Songkhla IDC are reportedly unaccompanied. Detainees told BROUK and Fortify Rights that they are confined to overcrowded cells, where they sleep side-by-side on the floor. Detainees in Songkhla said that they lack access to healthcare, mental health services, and opportunities to exercise or be in open air for any amount of time.

International law forbids arbitrary, unlawful, or indefinite detention, including of non-nationals. A state may only restrict the right of liberty of migrants in exceptional cases following a detailed assessment of the individual concerned. Any detention must be necessary and proportionate to achieve a legitimate aim. Failure to consider less coercive or restrictive means to achieve that aim may also render the detention arbitrary.

The Government of Thailand’s promise to take human trafficking seriously and to prosecute those responsible has not been matched by action with respect to the trafficking of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar. Witness intimidation by security forces has marred a high-profile human trafficking case involving 91 defendants accused of involvement in the trafficking of Rohingya and Bangladeshis. The chief investigator in the case, Police Major General Paween Pongsirin, fled to Australia in November 2015, claiming to be in fear for his life, raising further concerns about Thailand’s commitment to prosecute human traffickers. Meanwhile, the continued detention of survivors of trafficking in Thailand, including in government-run shelters, puts them at greater risk of being re-trafficked in addition to other abuses.

In Malaysia, BROUK and Fortify Rights are extremely concerned for the well-being of Rohingya survivors from the May 2015 boat crisis, who reportedly remain detained in the Belantik IDC, where access for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and service providers is extremely limited. Thousands of other Rohingya may be being held indefinitely in poorly equipped IDCs located throughout Malaysia.

Rohingya refugees told BROUK and Fortify Rights that Malaysian authorities routinely use the threat of arrest to extort money and property from them, particularly those who are unable to produce proper documentation.

While UNHCR officials in Malaysia recognize that informal UN documentation provides invaluable informal protection to refugees in the country, changes in UNHCR’s registration practices have considerably narrowed access to asylum procedures for Rohingya refugees, leaving many without any documents and at risk of serious security concerns, including the possibility of indefinite detention. Rohingya refugees repeatedly said the lack of access to UNHCR registration is the single-most important issue they face in Malaysia, followed by the lack of access to affordable healthcare and the lack of access to livelihoods.

Despite the lack of protections for refugees in Malaysia, the country remains the primary destination for Rohingya fleeing Myanmar. This is primarily because Malaysia is a predominantly Islamic country where many Rohingya have family or social networks. Human trafficking syndicates have preyed on Rohingya refugees’ desire to travel to Malaysia. Malaysian authorities have failed to prosecute those involved in trafficking Rohingya to Malaysia via Thailand, and in this context of impunity, new human trafficking networks may have been established, targeting Rohingya in Indonesia.

While Indonesia was widely praised for opening its borders to Rohingya refugees after Acehnese fishers courageously saved more than 1,000 survivors of human trafficking in May 2015, our findings suggest the authorities deserve little to none of the praise intended for the fishers. Indonesian authorities continue to frame the situation of Rohingya refugees in Indonesia as an emergency response and continue to confine Rohingya survivors from the May 2015 boat crisis to poorly equipped camps in Aceh province. Rohingya refugees living in the camps are not free to leave the camps and must depend on service providers for basic necessities. Rohingya refugees living in other parts of Indonesia with UNHCR status lack freedom of movement in the country.

Moreover, in the course of travels for this briefing, Indonesian authorities effectively deported BROUK President Mr. Tun Khin on March 6, following a “meet and greet” with a community of Rohingya refugees in Makassar on March 4. Immigration authorities took Tun Khin’s UK passport and questioned him about his activities in Indonesia. Following the questioning, immigration officials required him to sign a statement written in the Bahasa language. The authorities refused to provide him with a copy or allow him to take a photograph of the statement. Upon return of his passport, Tun Khin departed the country on March 7.

In each country visited, the rights of Rohingya refugees are being continually violated and protections are lacking.

These abuses only compound the realities Rohingya Muslims face in their native Myanmar, where authorities have systematically persecuted them for decades. In Rakhine State, more than 145,000 Rohingya men, women, and children are confined to more than 65 squalid internment camps. Rohingya and other Muslims were displaced from their homes in 2012 following violent clashes with local Rakhine Buddhists and targeted, coordinated, state-sanctioned attacks. More than 1 million Rohingya in Myanmar are denied freedom of movement and equal access to citizenship rights, rendering most stateless. While many Rohingya in Myanmar hold out hope that the incoming government, led by the National League for Democracy, will reverse decades-old abuses and persecution, the root causes of the regional Rohingya refugee crisis remain unaddressed.

Until the situation in Myanmar changes, Rohingya will continue to flee, and until protections for refugees improve in Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia, Rohingya will continue to suffer needlessly.

“I have no job and no earnings and that is difficult. It is not easy to get a job without a UN card,” lamented an undocumented Rohingya-refugee woman living in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia since June 2014. “I’m not in good health. My family is separated . . . Everywhere is trouble.”

Read more here.