Abuses Against Child Domestic Workers in El Salvador

Seventeen-year-old Flor N. works thirteen hours each day as a domestic worker in San Salvador, beginning at 4:30 a.m. “It’s heavy work: washing, ironing, taking care of the child,” she told Human Rights Watch. When she finishes her workday, she heads to her fifth grade evening class. “Sometimes I come to school super tired,” she said. She was drinking a soda as she talked and looked jittery from too much caffeine. She continued, “I get up at 2 a.m. to go to work. I leave school at 7:30 p.m. and get home about 8 p.m. I have dinner and sleep for about five hours.”

When she rises at 2 a.m. to return to work, she must walk one kilometer along a dangerous road to catch a minibus. “At 2 a.m. there are gangs where I live. This morning there was a group from a gang that tried to rob me of my chain,” she said.

She receives 225 colones (¢) each month, about U.S.$26, for her labors. “Sometimes there’s a lot of laundry.” She pointed to a barrel-sized trashcan to show us how much. “In the morning I give milk to the baby. I make breakfast, iron, wash, sweep.” The only domestic worker for a household of four adults and a three-year-old, she is also responsible for preparing their lunch, dinner, and snacks, and she watches the child. “Sometimes I eat, but sometimes I am too busy,” she told us. “There is no rest for me. I can sit, but I have to be doing something. I have one day of rest” each month.

“They deduct if I make errors. One time the lady lost a chain that they said was worth ¢425 [U.S.$48.50]. I had to pay for it. They said that I wore chains. I preferred to pay rather than lose my job.”

She would like to go to school during the day, because daytime class sessions are longer. She would probably be more alert during the day as well. But her workload prevents that. She attends classes at one of San Salvador’s night schools, programs that are designed for domestics and other children who work during the day.

In some respects, Flor is better off than many of her peers. Child domestics in El Salvador may work for up to sixteen hours each day, sometimes with only one or two days off each month. Over 60 percent of girls surveyed for a 2002 study by the International Labour Organization’s International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) reported physical or psychological mistreatment, including sexual harassment, from their employers.

Unlike Flor, many domestic workers are not able to continue their education. Domestic workers typically drop out from school between the ages of fifteen and seventeen, IPEC found, most commonly because their work hours conflict with the school day or because of the cost of school fees, uniforms, school supplies, transport to and from school, and other educational expenses. Others are able to attend night classes, but traveling to and from school at night involves increased risks to their safety. Even those who are able to go to school during the day report that their work sometimes interferes with their schooling when they do not have time to do their homework, fall asleep during class, or miss days of school.

For some, it is the cost of education that drives them into hazardous forms of work. We heard accounts of children who work as domestics in order to earn money for their school fees, uniforms, and school supplies, which may total as much as $300 per student each year.

It is difficult to estimate the total number of child domestic workers in El Salvador with any accuracy. Because domestic work takes place in private households, those who perform this labor are more difficult to track than other workers in the informal sector. “They are the most invisible of the invisible,” said Nora Hernández, a community worker with Las Dignas, a women’s rights group in San Salvador.

The Salvadoran census bureau collects data on the number of workers who are employed in domestic service, but it does not disaggregate those who are children under the age of eighteen from young adults. Based on statistical projections employing those data, IPEC has concluded that approximately 21,500 youths between the ages of fourteen and nineteen work in domestic service. Some 20,800, over 95 percent of these youths, are girls and women. Nearly one-quarter of the domestic workers surveyed by IPEC began working between the ages of nine and eleven; over 60 percent were working by age fourteen.

This report examines domestic work by children who work in other people’s households, including the households of relatives. Many of these children live in the homes where they work; others travel to and from their workplaces each day. The report does not address domestic work by children in their own homes. In this report, the word “child” refers to anyone under the age of eighteen.

Much of the domestic work by children documented in this report interferes with their education and involves economic exploitation and hazardous work, in violation of Salvadoran and international law. The Convention on the Rights of the Child prohibits economic exploitation and the employment of children in work that is likely to be hazardous, interfere with their education, or be harmful to their health or development.4 Domestic work by children under such conditions also ranks among the worst forms of child labor, as identified in International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 182, the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention. Under the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, children under the age of eighteen may not be employed in work which is likely to harm their health, safety, or morals. Prohibited labor includes work that exposes them to physical, psychological, or sexual abuse; forces them to work for long hours or during the night; or unreasonably confines them to their employers’ premises.5 El Salvador has ratified both of these treaties. In addition, the Salvadoran Constitution provides that the state has the duty to protect the physical, mental, and moral health of children; and the Salvadoran Labor Code prohibits the employment of children under the age of eighteen in hazardous or unhealthy work.

Government officials consistently deny that children, particularly those under the minimum employment age of fourteen, work in domestic service in large numbers. “Really the work of minors in domestic service is very little. Few minors are working as domestics. Very few,” said José Victor Orlando Orellana Maza, director-general of labor when Human Rights Watch spoke with him in February 2003. Later in our interview, he told us, “We have had isolated cases of minors. But the work of those under fourteen is practically zero. The employers are not contracting with minors.”

“It’s a touchy area with the government. There’s a reluctance to group it along with the other forms of child labor,” said Benjamin Smith, chief technical advisor for the ILO in El Salvador. “We know that hundreds experience very clear exploitation. . . . Some are in a situation similar to slavery.”

The labor code excludes domestic workers from many of the most basic labor rights. For example, they do not enjoy the right to the eight-hour workday or the forty-fourhour work week guaranteed in Salvadoran law, and they commonly receive wages that are lower than the minimum wages in other sectors of employment. The exclusion of all domestic workers from these rights denies them equal protection of the law and has a disproportionate impact on women and girls, who constitute over 90 percent of domestic workers. El Salvador is the only Central American country to participate in an ILO Time-Bound Programme, an initiative to eliminate the worst forms of child labor within a period of five to ten years. Although the IPEC study on domestic work concluded that its use outside the home was among the worst forms of child labor, the Salvadoran government has not identified domestic labor as one of the priority areas of emphasis for its TimeBound Programme.

* * *

This is Human Rights Watch’s tenth report on child labor. Our first reports addressed slavery, bonded child labor, and other practices akin to slavery that violate the Convention on the Suppression of Slave Trade and Slavery; the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery; and the Forced Labour Convention. In subsequent reports, we have examined other forms of child labor that amount to economic exploitation and hazardous work, in violation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and those that rank among the worst forms of child labor as identified in the ILO’s Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention. To date, we have investigated bonded child labor in India and Pakistan, the failure to protect child farmworkers in the United States, child labor in Egypt’s cotton fields, abuses against girls and women in domestic work in Guatemala, the use of child labor in Ecuador’s banana sector, child trafficking in Togo, and the economic exploitation of children as a consequence of the genocide in Rwanda.

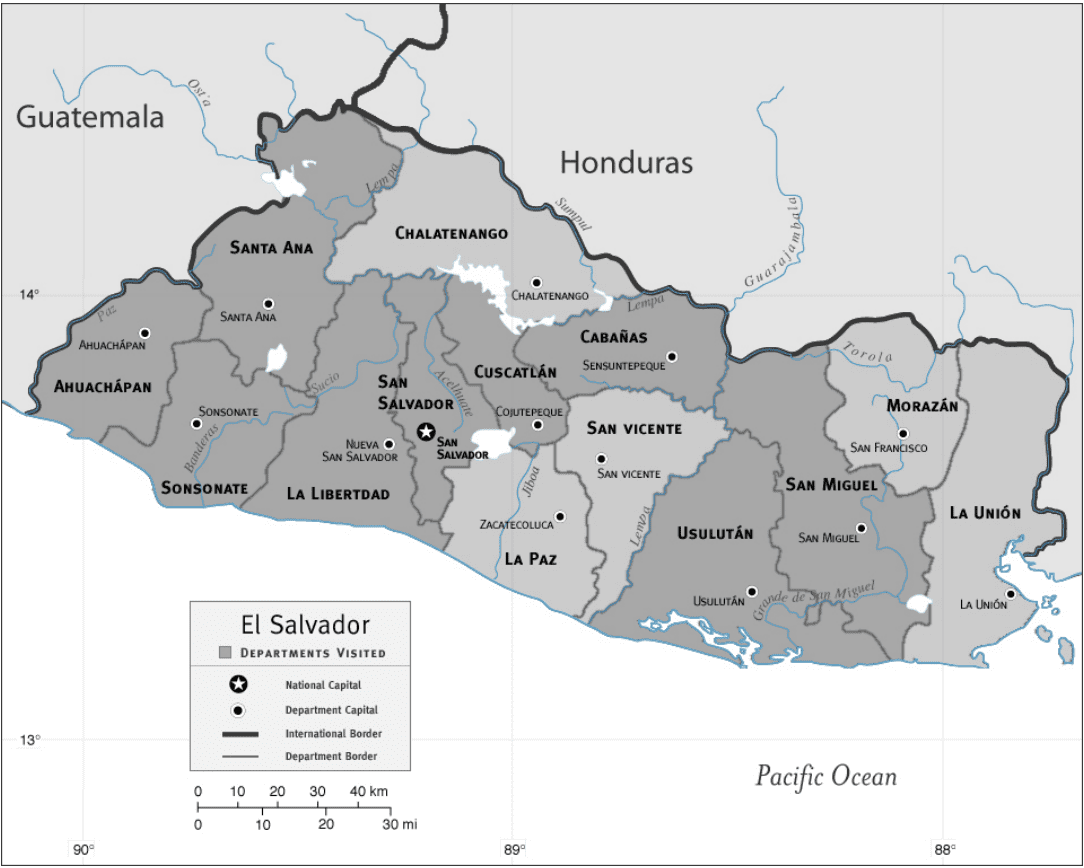

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in El Salvador in February 2003 and subsequently by telephone and electronic mail from New York. During the course of our investigation, we spoke with fifteen current and former domestic workers and over fifty teachers, parents, activists, academics, lawyers, and government officials.

We assess the treatment of child domestic workers according to international law, as set forth in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, and other international human rights instruments. These instruments establish that children have the right to freedom from economic exploitation and hazardous labor, the right to freedom from discrimination based on their gender, and the right to an education, among other rights.

Read more here.