A Hidden Scourge

Southeast Asia’s refugees and displaced people are victimized by human traffickers, but the crime usually goes unreported.

Security threats are no longer just about military confrontation, territorial disputes, and nuclear proliferation. They also arise from nonmilitary dangers such as climate change, natural disasters, infectious diseases, and transnational crimes. Among these nontraditional security threats, human trafficking looms large, especially in Southeast Asia, where natural disasters and military conflicts lead to displaced people and refugees, who are particularly vulnerable to this heinous crime.

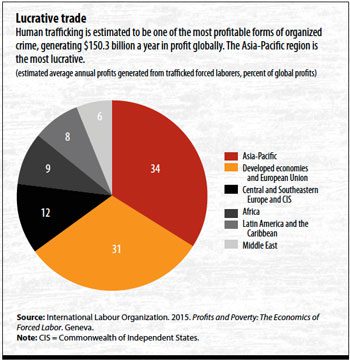

In Southeast Asia and elsewhere, nontraditional security threats have two defining features: they are transnational and complex. The scourge of human trafficking, sometimes called “modern slavery,” affects some 40 million men, women, and children trapped in a horrendous web of forced labor, sexual exploitation, and coerced marriage (ILO and Walk Free Foundation 2017). According to some estimates, human trafficking is now one of the world’s most lucrative organized crimes, generating more than $150 billion a year. Two-thirds of its victims, or 25 million people, are in East Asia and the Pacific, according to the Walk Free Foundation’s Global Slavery Index 2016 (pdf).

These shocking figures are only estimates, since accurate data are difficult to obtain, largely because human trafficking is underreported, underdetected, and thus underprosecuted. It remains largely a hidden crime, since victims are reluctant to seek help for fear of intimidation and reprisals. Victims, not perpetrators, are often the ones who suffer physical abuse and prosecution for illegal migration.

Leading destinations

Alarming trends in human trafficking in East Asia and the Pacific have raised the urgency of dealing with the menace. More than 85 percent of victims were trafficked from within the region, according to the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2016 (pdf), published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes (UNODC). China, Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand are destinations from neighboring countries. Within Southeast Asia, Thailand is the leading destination for trafficking victims from Cambodia, Lao P.D.R., and Myanmar, according to the Walk Free Foundation’s Global Slavery Index 2016. Malaysia has been a destination for victims from Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Fifty-one percent of victims in East Asia were women, and children comprised nearly a third, according to the UNODC report.

During 2012–14, more than 60 percent of the 7,800 identified victims were trafficked for sexual exploitation. Females are also victims of domestic servitude and other forms of forced labor. In many cases, the women and children are from remote and impoverished communities. Forced marriages of young women and girls are rampant in the Mekong region of Cambodia, China, Myanmar, and Vietnam.

The rise in child trafficking in the region is linked to the alarming increase in online child pornography, including live streaming of sexual abuse of children. It is a lucrative business estimated to generate $3–$20 billion in profit a year. Countries such as Cambodia and Thailand have been identified as major suppliers of pornographic material.

Many Southeast Asian victims migrate in search of paid jobs but wind up forced to labor in fishing, agriculture, construction, and domestic work, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Most of them are men who cannot repay exorbitant fees charged by unauthorized brokers and recruiters and so become vulnerable to debt bondage and other forms of exploitation, according to the US Department of State’s Trafficking in Persons Report 2018 (pdf). The Asia-Pacific region is the world’s most lucrative when it comes to forced labor (see chart). Forced labor in the fishing industry has been widely reported in Cambodia, Indonesia, and Thailand. Victims are paid too little or not at all for working up to 20 hours a day.

Conflicts, disasters

Traffickers also choose their victims from among the massive numbers of people displaced by armed conflict and natural disasters, who in their desperate attempt to find safety and protection are particularly vulnerable. Typhoons and other natural disasters are becoming more intense and frequent in Southeast Asia because of climate change, adding to the flow of potential victims, including children who are orphaned or separated from their families. According to the IOM’s World Migration Report 2018, 227.6 million people have been displaced since 2008.

After Typhoon Haiyan, one of the strongest tropical storms ever recorded, struck the Philippines in 2013, survivors were reportedly forced to work as domestic servants, beggars, prostitutes, and laborers. Drought-affected migrants have been smuggled from Cambodia into Thailand (Calma 2017; Tesfay 2015). These migrants tend to take illicit and dangerous routes, making them easy prey for criminal networks. Yet despite growing evidence that climate change increasingly drives forced migration, the link with human trafficking remains relatively unexplored. The IOM notes that climate change and natural disasters are rarely regarded as contributing to human trafficking in global discussions or national-level policy frameworks.

Conflicts in Myanmar and the southern Philippines are another major source of vulnerable refugees, according to the US Department of State’s Trafficking in Persons Report 2017. More than 5,000 Rohingya from Myanmar have been trafficked or smuggled into various parts of Bangladesh, rescued by police, and brought back to refugee camps. Traffickers have reportedly also preyed on ethnic minorities affected by internal conflicts in Myanmar. The country’s Karen, Shan, Akha, and Lahu women are trafficked for sexual exploitation in Thailand, while Kachin women are sold as brides in China. Armed conflict makes children even more vulnerable. The United Nations has reported that armed groups in the Philippines, including Moro rebels and communists, recruit children, at times through force, for combat and noncombat roles.

International protocols

What is being done to fight human trafficking? Two international agreements regard human trafficking as a transnational crime: the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, and the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, also known as the Palermo Protocol. The Palermo Protocol divides the offense into three components: the act of recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, and receipt of persons; the means—the use of force and other forms of coercion, such as abduction and deception; and the purpose—for prostitution, forced labor and slavery, and the removal of organs.

The core of the anti-trafficking regimes is protection of borders by controlling the flow of illegal migration. Article 11 of the Palermo Protocol, for example, requires states to strengthen border controls to prevent and detect trafficking in persons, and to enact legislation to prevent commercial carriers from being used for trafficking. Protecting states’ security against human trafficking is also about helping them fight other associated crimes, including smuggling, prostitution, organ trafficking, and money laundering.

Aside from these two international legal regimes, Southeast Asia in 2015 adopted the ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children. This document (pdf) complements the international anti-trafficking framework. At the subregional level, the Coordinated Mekong Ministerial Initiative Against Trafficking also closely follows the Palermo Protocol framework and has led to several bilateral agreements aimed at greater cooperation between states in the Greater Mekong region. Beyond Southeast Asia, the Bali Process was set up in 2002 as a platform for dialogue among countries in the Asia-Pacific. Its goal is to raise awareness and build capacity to combat human smuggling, trafficking, and transnational crime. With the transnational nature of human trafficking, both international and regional regimes encourage governments to share information, coordinate policies and efforts to criminalize trafficking offenses, provide mutual legal assistance, protect victims, and prosecute offenders.

Corrupt officials

Still, huge challenges remain, notably the serious lack of accurate and reliable information on the scale and scope of trafficking, which makes it difficult to measure the effectiveness of anti-trafficking policies. The gap between the legal framework and the enforcement of relevant laws at the national level poses problems as well. Despite political will, law enforcement agencies lack the skills, knowledge, and resources to understand and respond to the evolving complexities of human trafficking. Collusion between corrupt government officials and criminal networks is another severe problem. Traffickers are known to enlist the help of corrupt officials in recruiting victims and moving them across borders. The discovery of mass graves of trafficking victims along the border between Malaysia and Thailand in 2015 is gruesome evidence of such collusion; a Thai general and police officers were among 62 people convicted of human trafficking and other crimes connected with the case, according to news reports.

Finally, victims of trafficking receive inadequate protection and assistance. A common critique of anti-trafficking regimes is that most efforts have focused on criminalizing and prosecuting traffickers, as opposed to preventing the crime and protecting its victims. The focus on criminalization and prosecution may have increased awareness, but more should be done to prevent trafficking through effective law enforcement and efforts to educate vulnerable groups about its dangers.

Similarly, there must be greater effort to address the needs of victims. In addition to personal safety and security, victims need access to legal protection, health care, and temporary shelter, as well as assistance with repatriation and integration. The UNODC stresses the need to help victims overcome the trauma and stigma associated with trafficking and to build trust in law enforcement, so that victims seek help and cooperate in prosecuting traffickers.

The fight against human trafficking requires better national criminal justice systems to effectively enforce anti-trafficking laws, and these efforts must be part of a broader, multitrack approach that addresses the socioeconomic and political dynamics of trafficking. The complexity of the challenge means it cannot be tackled by any one actor, such as the state, or by focusing only on one aspect of the issue, such as sexual exploitation or forced labor. A comprehensive, more human-centered approach compels us to delve deeper into the other drivers of human trafficking, including poverty, severe exploitation, and political repression. This requires active participation and partnership between government and civil society groups, the private sector, and international foundations.